What’s often seen as cinema’s biggest flop is actually good – and it’s had a real impact on mainstream views of climate change, writes Gregory Wakeman.

W

When Waterworld splashed into US cinemas in July 1995, it did so with a belly-flop. Emphasis very much on the word flop. By the time Waterworld had arrived in the UK just two weeks later, its status as the most expensive film ever made at the time, its well-publicised production problems, average-to-negative reviews, and comparatively poor domestic box office performance had all combined to leave it dead in the water.

More like this:

– The most outrageous film ever made?

– The classic that’s saved lives

– The film that exposed our misogynistic culture

But 25 years on, Waterworld’s legacy and impact deserve a reappraisal. The film’s original screenwriter Peter Rader, who created the post-apocalyptic action adventure set in a future where the polar ice caps have melted and water covers the Earth, tells BBC Culture that Waterworld is actually “one of the most successful movies” in Universal’s vast catalogue.

With good reason, too, as Waterworld: A Live Sea War Spectacular has been key to Universal Studios theme parks ever since it debuted at the Hollywood site just a few weeks after the film was released. This attraction, which is one of the most popular rides at their locations in Singapore and Japan, too, has generated “billions in revenue” for the studio, according to Rader.

The Waterworld film attraction, such as this one in Singapore, has been one of the most popular at the Universal Studios theme parks (Credit: Alamy)

“Hundreds of millions of people have been exposed to the whole Waterworld idea. There’s a Jurassic Park zone. A Harry Potter zone. A Transformers zone. And they’re all multi-film franchises. They’ve all had at least three, in some cases seven, movies. Waterworld is just one movie. What does that tell you about the concept? It is so primordially appealing.”

Even as a film, Waterworld “is not as terrible as some critics claimed”, says Dr Sorcha Ni Fhlainn, a senior lecturer in Film Studies and American Studies at Manchester Metropolitan University. “It has some exciting set pieces and important points to make about our ecology, fossil fuels and environmentalism in the 1990s.”

And Waterworld has been critically reappraised in recent years, with The Guardian calling it a “cult classic in the making” and Forbes claiming that it is the “biggest box office bomb that wasn’t”. While Rader, who was replaced as writer by David Twohy when star Kevin Costner and director Kevin Reynolds joined, admits that he was ultimately disappointed with the tone of Waterworld, there is still plenty he adores about the finished film. Particularly its silent opening scene, which details how Costner’s Mariner distils his urine, and is regarded as such a fine example of visual storytelling that, Rader tells me, it’s taught at the University of Southern California’s renowned film school.

Too big to succeed

But if film fans are now beginning to appreciate Waterworld, why was it so eagerly dismissed and savaged when it originally hit cinemas? According to Liverpool John Moores University’s Yannis Tzioumakis, a perfect storm of issues blighted its release. First of all, there was a “huge increase in what’s called infotainment” – the combination of entertainment and industry news. This primarily covers “box office figures and film productions, especially if they have problems and go over budget”.

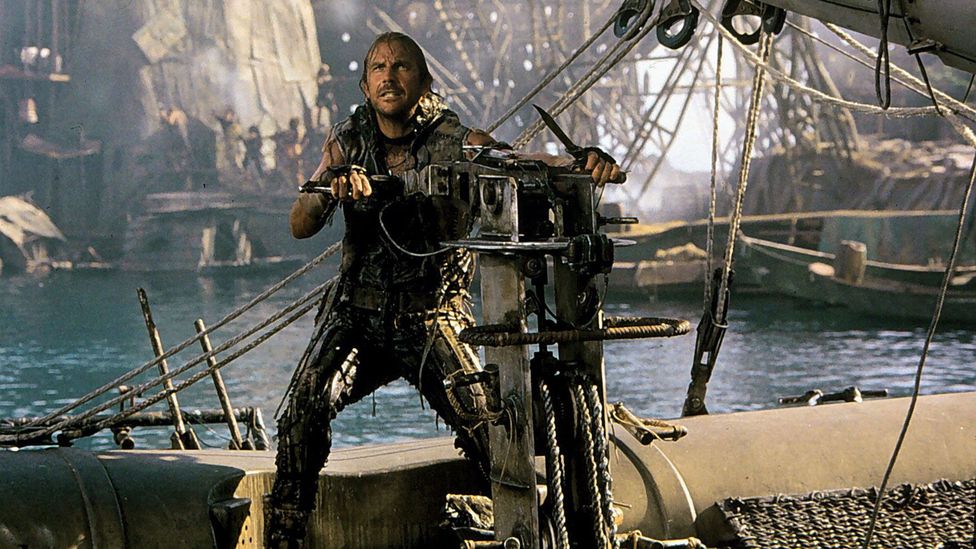

To keep Universal from forcing cuts on the script, Costner agreed to forfeit his percentage of the gross receipts (Credit: Alamy)

The doubling and then tripling of Waterworld’s production costs, the destruction of a multi-million dollar set in a hurricane, and Costner’s creative battle with Reynolds, which resulted in the director leaving production before editing was complete, soon became the perfect fodder for these shows.

On top of that, Costner’s incredible run of movies, which started in 1987 with No Way Out and The Untouchables, and was followed by Bull Durham, Field of Dreams, Dances With Wolves, Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves, JFK, The Bodyguard and A Perfect World, had already come to a crashing halt in 1994. Both Wyatt Earp and The War really were financial failures, as neither managed to gross even half of their budgets.

Around this time, Last Action Hero and Cutthroat Island bombed, too. These big budget blockbusters were the antithesis to the Hollywood indie wave movement of the 1990s, says Ni Fhlainn, especially with “the emergence of new directors like Quentin Tarantino” and a wave of “commercially successful and critically exciting films”.

But while Waterworld might be more entertaining than is generally remembered, there are two aspects of it that are disgustingly dated. Its lack of diversity is appalling, as the cast is almost entirely white and male. Rader acknowledges this aspect of Waterworld is particularly “glaring” in this “day and age”.

Waterworld has been criticised for its lack of diversity and oversimplified female representation (Credit: Alamy)

Waterworld’s treatment of its female characters isn’t any better. Ni Fhlainn notes how the film repeatedly shows a “limited understanding of female complexity”. A group called the Smokers is seeking a girl said to have a map to dry land tattooed on her back; according to Ni Fhlainn, the girl, Enola (Tina Majorino) and her guardian Helen (Jeanne Tripplehorn) are treated like “commodities to be traded or kept safe”, and all of their actions only “underscore the Mariner’s centrality to the plot”. Costner’s protagonist also offers Helen up as bait to the marauders.

Although Waterworld highlights just how white and male even recent Hollywood history is, it at least made a much more positive impact on mainstream discussions about climate change. Even back in the mid-1980s, when he first started work on the script, Rader knew that the melting of the polar ice caps would result in sea-levels rising just 35 feet, rather than putting everything under five miles of water as depicted.

That obviously would have resulted in a much dryer and less impactful movie, and Rader says that he and Reynolds were adamant that they wanted to make “something that heralded this urgent concern for the planet, but in the guise of a popcorn movie”. In order to achieve that, they filled Waterworld with a series of environmental references, including making the villainous Smokers’ headquarters the Exxon Valdez, an oil tanker that crashed off the coast of Alaska in 1989 and spilled 10.8 million gallons of crude oil in the ocean.

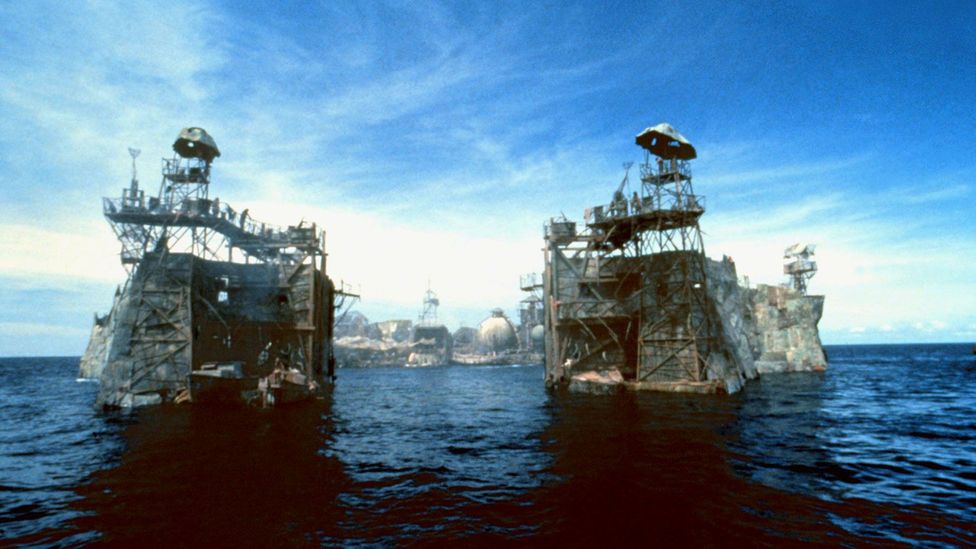

Waterworld envisages a future in which landmasses have been submerged and communities survive on floating atolls (Credit: Alamy)

Waterworld originally included many more references to the impact of humans on the globe – including the revelation that Dryland, the last place on Earth not covered in water, is actually the summit of Mount Everest. The original plan was to show this with the discovery of a plaque that detailed how Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay had climbed this peak. Rader tells me that Reynolds told him this “was the moment he knew he wanted to make the film”, comparing it to the “Planet of the Apes scene when you see the crown of the Statue of Liberty.” Unfortunately, according to Rader, when Costner “basically took over editing” on Waterworld the finale was removed, which Rader calls one of a “few missed opportunities” for the film.

While Waterworld doesn’t even explicitly mention global warming, Merchant says it would have undoubtedly made viewers inquire about the crisis and “seek out more reliable sources to better understand” it. Dr Peter Gleick, a world-renowned expert on water and climate issues, echoes this sentiment, saying that as an example of climate-fiction, Waterworld is “even more relevant and on target today than it was when it came out”.

“These films offer us little glimpses into the future. However realistic they are or may not be, they do provide us with the opportunity to think that maybe we should doing things to stop these bad things from happening.” Rader’s work on Waterworld has even had repercussions beyond the big screen. In April 2019, he was invited to be a part of the very first round table on Sustainable Floating Cities at the United Nations Headquarters in New York City, alongside a team of specialists. A model designed by architect Bjarke Ingels was created for the occasion and placed in the middle of the table. Rader couldn’t believe his eyes when it “looked exactly like our Atoll from Waterworld… It was immensely satisfying to be in a room where concepts I came up with three decades earlier could actually help us.”

There’s even more to Waterworld’s environmental impact, too. Costner was so inspired by his time on the film that he bought Ocean Therapy Solutions, a company that specialises in separating oil from water – a process which is used to mitigate oil spills – and that sold its technology to BP after the 2010 Deepwater Horizon industrial disaster. It’s now been predicted that the Arctic sea ice, which plays a vital part in controlling the worldwide climate, could disappear as early as 2035 – so the next time someone calls Waterworld a flop, tell them that one day, it might just help to save the planet.

Love film and TV? Join BBC Culture Film and TV Club on Facebook, a community for cinephiles all over the world.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.