Paul Verhoeven’s flop about Las Vegas strippers has long been a camp classic. But, 25 years on, it’s time to recognise it as a bona-fide horror story too, writes Hugh Montgomery.

I

It might be one of the great vindications in cinema history. In 2015, actress Elizabeth Berkley made a surprise appearance at an anniversary screening of Showgirls at LA’s Hollywood Forever Cemetery. Introducing the movie, she was cheered on by thousands of adoring fans – going some way to compensate for the undue vilification she had received for her performance 20 years before. Footage of the evening opens You Don’t Nomi, a new documentary about the notorious film; as well as finally giving Berkley her due, it capped off Showgirl’s ascent from tawdry Hollywood misfire to cult classic.

Warning: This article contains strong language that might cause offence

More like this:

– The most outrageous film ever made?

– The classic that’s saved lives

– A masterpiece about US racism

As the story goes, in the mid-1990s, riding off the box-office success of their luridly Hitchcockian erotic thriller Basic Instinct, director Paul Verhoeven and scriptwriter Joe Eszterhas had something of a free rein for their next project – which took the shape of a film that made Basic Instinct look positively austere. A melodrama about backstabbing exotic dancers in Las Vegas, it was proudly sold as the first film to receive a wide, mass-market release on an adult-only NC-17 rating – which had replaced the old ‘X’ rating in 1990 – and controversy was ensured.

Showgirls’ central plot revolves around the rivalry between two Las Vegas dancers: Cristal Connors (Gina Gershon, left) and Nomi Malone (Elizabeth Berkley, right) (Credit: Alamy)

Unfortunately, though, that provocation did not translate into ticket sales. Instead, overwhelmingly bilious reviews were matched by a disastrous commercial performance. On a $45 million budget, it made back just north of $20 million in the US, and $37 million worldwide.

On its initial release, no-one seemed to know how to take a film that, alongside the expected, copious nudity, featured a hysterical performance from Berkley as its career-climbing protagonist Nomi Malone; sets and costuming that stretched the tastelessness of Sin City to its limit; unhinged, hyperkinetic sex scenes; and jarringly crass dialogue that peaked with an exchange between Nomi and her nemesis Cristal Connors (Gina Gershon) about their shared childhood love of eating ‘Doggy Chow’ (that’s dog food, for the uninitiated).

A camp redemption

It was no time at all, however, before people did find a way to enjoy it: in her drubbing of the film, The New York Times’ Janet Maslin identified that what Verhoeven and Eszterhas had created was “an instant camp classic” and lo, with the exhilarating whiff of disaster surrounding it, that was what it became – celebrated as a gloriously, unintentionally bad movie whose excessive spectacle was matched by readily-quotable quips.

The studio behind it, MGM, were also extremely quick to capitalise on the joke. Less than a year later, in 1996, they rereleased it in US cinemas as a ‘midnight movie’, and that was followed up in 2004 by a ‘VIP edition’ DVD, which included a “pin-the-pasties-on-the-showgirl” game, and a mocking commentary from writer and super-fan David Schmader, who was already known for the comic ‘annotated’ screenings he hosted across the US. However perhaps the most important element of the film’s incredible afterlife was the way in which it was embraced by the drag community, with drag queen-hosted screenings continuing to be a tradition today.

But in recent years, a shift has happened again: a pushback against the whole notion that the film is deserving of the consolation prize of irony. Instead, a range of criticism has reappraised Showgirls as a serious piece of work – key among them Canadian critic Adam Nayman’s 2014 book It Doesn’t Suck: Showgirls and, now, You Don’t Nomi. The latter, which premiered at last year’s London Film Festival, is the work of first-time director Jeffrey McHale who recalls first seeing it a decade after its original release on DVD. “I had a very similar experience that a lot of the contributors [in my film] did where your heart starts racing and you get this feeling of excitement like ‘how did this get made?'”. His film, though, is a relatively sober inquiry into Showgirls’ enduring legacy, which incorporates a diverse range of opinion (including from Nayman) and also considers it as part of the whole Paul Verhoeven oeuvre.

Starship Troopers is among Verhoeven’s other US films that target the country’s fetid socio-political landscape (Credit: Alamy)

Filmmaker and journalist Catherine Bray is another who has come to take the film more seriously over time. “The more times you watch it, the more you realise how intentional it all is. It sounds mad but it is a film that rewards repeat viewing,” she tells BBC Culture.

A misunderstood satire?

What is that intention, though? In hindsight, it would be extremely difficult not to read Showgirls as satirical, in the context of Verhoeven’s career. At that stage, after all, the Dutch filmmaker was in the pomp of his Hollywood phase, which saw him use popcorn genres as a way to critique his adopted homeland’s socio-political landscape: there was Robocop’s shots at law enforcement and corporate supremacy and Starship Troopers’ caustic indictment of the country’s more fascistic impulses and jingoistic foreign policy in the guise of a ‘big bug’ movie.

Showgirls may come with more rhinestones attached, but it’s even more searing in its depiction of a dehumanised world, whose ultra-consumer capitalist worldview is encapsulated in one typically bald exchange between Nomi and Cristal: “You are a whore, darlin”, “No, I’m not!” “We all are, we take the cash, we cash the check, we show ’em what they wanna see.” The fact Showgirls wasn’t immediately understood as satire speaks to an implicit, and possibly patriarchal, bias in film criticism about what tenors of filmmaking are accorded intellectual respect – something Nayman seems to get at in You Don’t Nomi when he notes how “Verhoeven was widely understood in America as a satirist and as a social commentator as long as the primary texture of his films was violence … [whereas] he makes a movie that has a texture that is more overtly sexual [and] all of a sudden people didn’t think he was a satirist or a commentator … they just sort of said ‘what a pervert’.”

There is another, more literal, level on which it functions as satire too, of course: as a satire of the entertainment business, and the vulgarity and exploitation therein, on-and-off screen. And when it comes to self-referentialism, you don’t need to stop there: “It’s a satire of Hollywood but it’s also a satire of satires of Hollywood,” Bray suggests. “You get that hall-of-mirrors effect with the film.”

It’s at this point at which both the out-and-out Showgirls sceptics and the camp appreciators may roll their eyes at the more serious Showgirls aficionados and tell them they’re as over-earnest as Nomi Malone is when she insists she is a dancer, not a stripper. But the perfect mediator for any Showgirls debates has been provided by Nayman’s now much-cited classification of the film (used as a framing device in You Don’t Nomi) as a ‘masterpiece of shit’: a film that is both terrible and brilliant at once, and proves that need not be a contradiction.

Kyle Maclachlan’s Zack is among the many men who show total contempt for women in the film (Credit: Alamy)

Indeed, the way in which Showgirls is now seen to defy critical binaries is reflected in how the British Film Institute’s annual LGBTQ+ Flare festival had planned to mark the film’s 25th anniversary in March, before it was cancelled due to the current coronavirus situation. Their celebratory evening would have catered to those who enjoy it as trash, art, or both alike, with a screening of McHale’s reflective essay followed by an uproarious ‘Shade-Along’ screening of the film itself, hosted by drag performer Chris Weller, aka Baby Lame, and featuring various bits of call-and-response, games and pantomiming of the action on screen.

A straight reading

Rewatching it now, however, you sense that the prism through which its predominantly viewed may change yet again: for within the current climate, it is most potent neither as camp, nor as satire, but as a straight-shooting portrait of the rancid, unchecked misogyny within the entertainment industry and beyond. Or rather if it is deranged, then that is merely a pretty accurate reflection of the diseased culture it depicts. Perhaps the late French New Wave director Jacques Rivette had it right back in 1998 when, in praising Showgirls, he noted that “it has great sincerity and the script is very honest, guileless”.

That honesty is most horrifying when it comes to gender relations. It is impossible to think of another mainstream studio film in which the systematic abuse and exploitation of women is so unflinchingly depicted. Where the female body is so recurrently grabbed, slapped or pawed-at, verbally demeaned or physically assaulted. Where every man, from Nomi’s initial employer and warped father-figure, strip club manager Al (Robert Davi), to her two love interests – dancer James (Glenn Plummer) and oleaginous ‘entertainment director’ Zack (Kyle MacLachlan) – demonstrates total contempt for women. The film’s defining sentence, in fact, comes not from one of the female leads but the strip-club punter who says: “In America, everyone’s a gynaecologist”.

It’s a line that, in the satirical reading of the film, might seem designed to provoke an appalled laughter – as, similarly, might the scene of a scornful director demanding that Nomi rub her breasts with ice in the middle of an audition to make her nipples hard.

But the most appalling thing, of course, is that there is absolutely nothing absurd or hyperbolic about such moments. Four years on from the ‘pussy grabbing’ tape that prefaced the election of a president, and three years on from the beginning of the belated reckoning with Harvey Weinstein, the gross, brutal misogyny at the core of the Western establishment is now out in the open, even as the evidence of it keeps on coming thick and fast.

This behaviour was always known to many, of course; it just proceeded under a de facto ‘don’t ask don’t tell’ policy without much serious mainstream challenge. Only last week, in a fantastic essay in the New Yorker about Verhoeven’s Starship Troopers, the critic David Roth wrote that “it has become clear, in these last decades of decadence, decline, towering institutional violence, and rampant bad taste, that American life is stuck somewhere inside the Paul Verhoeven cinematic universe”, pointing to how the dystopias of Starship Troopers, Robocop, as well as the director’s Philip K Dick adaptation Total Recall, have come to pass. More straightforwardly, however, Showgirls is, and has always been, stuck inside American life, not prescient so much as a rare truth-teller.

Misogynist or about misogyny?

Of course, however stark its truths may be, the extent to which it is a film about misogyny, or a misogynistic film, is a moot point. This is, after all, a film made by two middle-aged men who were hardly apart from the exploitative system that the film is arguably critiquing: Eszterhas’ CV, in particular, is filled with scripts, like the male-fantasy-dressed-up-as-empowerment-fairytale Flashdance and the post-Basic Instinct erotic thriller Sliver, whose objectification of its female characters seems rather more cut-and-dry.

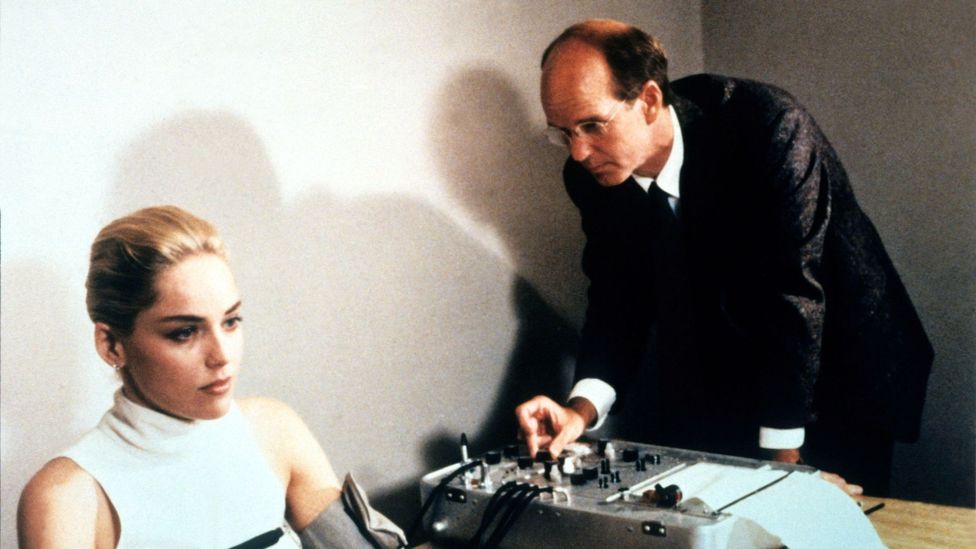

Paul Verhoeven and Joe Eszterhas’ previous film Basic Instinct was a substantial hit that gave them free rein to make Showgirls (Credit: Alamy)

And then there’s Basic Instinct itself: Eszterhas and Verhoeven’s first collaboration and another film that has been both slated as sexploitation and heralded as satire. The most serious question around it involves its most notorious moment, when Sharon Stone’s character crosses and uncrosses her legs during a police interrogation. You Don’t Nomi references the disturbing, repeated allegation from Stone that she was tricked into not wearing underwear by Verhoeven, who she says assured her while filming the scene that “we won’t see anything”.

In all the debates surrounding Showgirls, there is no moment more contested than the scene towards the end of the film, when Nomi’s friend Molly (Gina Ravera) is violently raped by a famous rock star. It’s a scene that seems to come out of nowhere – occurring as it does in the middle of a party celebrating Nomi’s triumphant opening night as a principal dancer, and with the rapist having earlier been set up as Molly’s cheesily innocuous celebrity crush. And, some would say, it is not just unexpected, but unearned. Add in the fact that it involves the abuse of the film’s sole significant woman of colour – whose rape serves as a catalyst for the white heroine’s final evolution into an avenging angel – and it is not hard to see why it has been the source of the film’s most damning appraisals. McHale doesn’t mince his words in his judgement of it. “It’s completely offensive. I think it’s not really necessary… [Verhoeven] used Molly’s brutalisation as a way for Nomi to find herself and I think that’s disgusting.”

On the other hand, you could argue that the brutal disruptiveness of this scene is what makes it the film’s most necessary moment. “I think it is one of the things that makes it a serious film,” says Bray. “[If you did] a depiction of Vegas at that time, and of the power dynamics between very famous stars and the people on the periphery, and pretended the fairytale version of it is true, that would be colluding with the Weinsteins of this world – whereas Verhoeven is saying ‘this goes on, and it goes on in the next room to where glamorous parties are taking place’.”

Whatever your feelings about the sequence, it determinedly interferes with the consumption of Showgirls as a work of camp fun. Schmader used to skip the scene in his ‘annotated’ screenings, and the BFI confirmed to me ahead of the subsequently-cancelled ‘Shade-Along’ screening that they, too, would not would not screen that scene. “It was felt both by the festival and [Weller] that it doesn’t fit the spirit of the festival and what we’re trying to celebrate with the event,” they said, while adding that “we’re not going to pretend that scene doesn’t exist. [Weller] will contextualise the missing scene and explain that it doesn’t have a place at the event.”

This kind of excision seems sensible on one level, though it does call into question the treatment of Showgirls as a comedic collective experience. How valid is it to nip and tuck a film so that it becomes the one you want to see, rather than the one that was actually made?

Shameful treatment of its star

As troubling as anything that happens on screen in Showgirls were the consequences it had for Berkley. “As an actress, Berkley is, to put it mildly, limited. She has exactly two emotions: hot and bothered,” sneered Owen Gleiberman of Entertainment Weekly, while Maslin described her as having “the open-mouthed, vacant-eyed look of an inflatable party doll”. Such personal ridicule sunk the 23-year-old actress’s career before it had even really begun, and a 2013 appearance on Dancing on the Stars has been her most notable recent screen credit.

The brutal final-act assault of Nomi’s best friend Molly (Gina Rivera, left) disrupts the viewing of Showgirls as a work of camp fun (Credit: Alamy)

The gratuitous nastiness towards a young woman aside, the tragedy is that these judgements are so patently wrong. Berkley gives the definition of a star turn: absolutely singular, and charged with a haywire electricity that makes it more essential than myriad dutiful performances that get nominated for Oscars. It benefits from the meta-authenticity that comes from a young entertainer pulling out all the stops for her shot at the big time, playing a young entertainer pulling out all the stops for her shot at the big time. But above and beyond that, it is an exhilaratingly surreal and abrasive performance, in which gestures and expressions are exaggerated to an inhuman level – whether she’s ravenously attacking a burger, churning up the water with the force of a jet-ski engine while having sex in a swimming pool, or being radioactively hostile to Cristal. “You can’t criticise the performance for not being realistic,” says Bray. “That’s like looking at an Andy Warhol and going ‘well those colours aren’t true to life. It’s a pop-art caricature’.”

Gershon, by contrast, is a commandingly relaxed presence, with all the Bette Davis swagger required of her – but it’s Berkley who is the truly mesmerising element, as well as embodying the film’s very core. Her Nomi is a character who seems to commodify herself by performing her selfhood, at all times, in capital letters, to bogus effect. In fact, the deeply artificial, insincerely over-sincere quality of Berkeley’s performance seems, in hindsight, to foreshadow the age of the reality TV star, and their cartoonish simulation of ‘real’ emotion.

Verhoeven has himself always stuck up for Berkley’s performance, telling the LA Times at the time that “the hate towards her character – an edgy, nearly psychotic character – is actually a compliment”. Yet to expose a young actor to a misogynistic shaming that perhaps could have been anticipated, as a by-product of your vision, is questionable, whatever the results. Certainly, Berkley’s fate continues to leave a bitter taste that only further complicates the flavour of the film as a whole.

“I think we’re still talking about Showgirls because we’re not done with it… I don’t think we’ve figured out what [it] means as a film,” says Mlotek at the very beginning of You Don’t Nomi – and we’re certainly unlikely to be done with it anytime soon. If Showgirls has already travelled in the critical imagination from embarrassing failure to camp classic, ‘masterpiece of shit’ and, now perhaps, searing cultural expose, then it feels like a wilfully unstable enough text to continue to defy any received wisdom. And just as we may never be done it, we’re probably not going to find an ideal way to watch it either. Raising the roof with drag queens, or with our hands clasped over our mouths in horror: nothing will quite suffice. In its wild, kaleidoscopic inconsistency, though, it is also as vital a cinematic experience as can be had.

You Don’t Nomi is available to watch on BFI Player and other streaming platforms.

Love film and TV? Join BBC Culture Film and TV Club on Facebook, a community for cinephiles all over the world.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.