Editor’s Note: We’ve removed our paywall from this article so you can access vital coronavirus content. Find all our coverage here. To support our science journalism, become a subscriber.

This originally appeared in the July/August issue of Discover magazine as “Titans of Immunity.” Support our science journalism by becoming a subscriber.

For years, Melanie Musson’s friends have marveled at her superpower: staying healthy no matter what germs are making the rounds. Colds and flu felled plenty of Musson’s dormmates in college, but the viruses always seemed to pass her by. “I never got sick once,” she says. “I got about five hours of sleep a night, I finished school in three years, and I worked 30 hours a week throughout. My best friends labeled me ‘the machine.’ “

Musson’s ironclad immune system also set her apart at her first job. While she was working at an assisted living facility, her co-workers succumbed to a stomach virus that was running rampant. Undaunted, Musson offered to cover their shifts. “There I was, the brand-new employee, getting as much overtime as I wanted. I wasn’t worried that I’d catch [the virus], because it just doesn’t happen.”

While the rest of us battle seasonal flu, chronic allergies and back-to-back wintertime colds, Musson and other immune masters glide through with scarcely a sniffle — something University of Pittsburgh immunologist John Mellors sees all the time. “People get exposed to the same virus, the same dose, even the same source. One gets very sick, and the other doesn’t.”

It’s only natural to wonder: Why do some people always seem to fall on the right side of this equation? And could our own immune systems approach the same level with the right tuneup?

Doctors have noted natural variations in the immune response among people since Hippocrates’ time, but the reasons remained elusive for centuries. New research, however, is starting to illustrate just how your genes, habits and past disease exposures affect the character and strength of your immune response. These discoveries are helping to define the parameters of a race in which people like Musson have a head start — and others have much more ground to cover.

In the Genes

The moment a virus, bacterium or other invader breaches your cells’ walls, your body rolls out a tightly choreographed defense strategy. The main architects of this process are a set of human leukocyte antigen (HLA) genes, which code for molecules that fine-tune the body’s immune response. So when a bacterium gets into one of your cells, your HLA genes churn out proteins that flag the cell as infected so that specialized immune cells will swarm in to destroy it. Other HLA genes activate cells that rein in the immune response, so it doesn’t destroy more than necessary.

Like fingerprints, everyone’s HLA gene assortment is unique. Your HLA genes give you a broad repertoire of immune defense tactics, but “that repertoire may be great for some microorganisms and lousy for others,” Mellors says. “It’s not like there’s one HLA type that’s highly immune to everything.” This genetic variation helps explain why you might catch every cold virus going around but haven’t gotten a stomach bug in decades. A Massachusetts General Hospital study found that some so-called HIV controllers — immune stalwarts who don’t develop AIDS from the virus HIV — have HLA gene variants that prompt specialized cells to swarm in and attack proteins key to the virus’ function.

(Credit: Shutterstock)

But your HLA genes aren’t the only ones that shape your immune resistance. The Human Genome Project has identified tens of thousands of gene variants that are more common in people who develop specific diseases and less common in people without these conditions.

Flagging these kinds of gene-disease links is a relatively simple matter, says immunologist Pandurangan Vijayanand of the La Jolla Institute for Immunology. After researchers identify a gene sequence that’s linked to disease, however, they need to “figure out what it is actually doing,” says Vijayanand. “How is this change in the sequence impacting the cell or causing the susceptibility [to disease]?”

To answer this question, Vijayanand and his team are creating what they call an atlas, to catalog which proteins each gene produces and how these proteins change the function of different cell types. For example, he has identified a gene variant that makes people more prone to asthma — a condition in which the body attacks its own healthy airway cells — by driving high production of proteins that rev up the immune response. Other gene variants appear to help people fight lung tumors by prompting their tissues to produce more T lymphocytes, specialized immune shock troops that kill cancer cells.

While a dizzying number of genetic differences remain to be cataloged, immunologists agree that, in general, these differences help explain why resistance to some pathogens can seem to run in families. People like Melanie Musson probably get a genetic leg up to some degree — Musson says her mother, father and siblings rarely get sick. Conversely (and unfairly), you might instead inherit a tendency to develop diabetes, recurrent strep infections or autoimmune diseases.

Context Matters

However anemic or hardy your innate immune arsenal, it supplies only the broad contours of your body’s resistance to threats. Environmental influences fill in the details, from where you live to your sleeping patterns to your history of previous infections.

In a 2015 Cell study, researchers studied more than 100 pairs of identical twins and how their immune systems responded to the flu shot. About three-quarters of the differences they saw were driven by environmental factors rather than genetic ones. The differences in twins’ immune systems also grew more pronounced the older they got, suggesting that outside influences continue to shape our immune potential over time.

Some of these influences show up in early childhood and may be hard to offset later on. Researchers have long known that children who live on farms are less likely to develop autoimmune diseases like asthma and allergies. An Ohio State University study from July 2019 hints at one reason why: Farm kids have a more diverse array of gut microbes than city kids, and the presence of some of these gut microbes predicts lower frequencies of immune cells that create allergic inflammation. Broad microbial exposure, in short, appears to train the immune system not to overreact to substances like animal dander.

But regardless of where you grew up, if you’re unlucky enough to catch certain disease-causing bugs, they can throw your immunity off balance for years. Cytomegalovirus, a relative of the virus that causes chicken pox, stages its attack by reprogramming the human immune system. Some of the virus’ proteins latch onto certain immune cells, interfering with their ability to fight invaders. Other proteins, according to research from the University Medical Center Utrecht, interfere with the expression of key human HLA genes. And since cytomegalovirus infections are chronic, the resulting immune deficits can go on indefinitely.

An Elective Arsenal

Naturally, you can’t control where you’re raised or what random pathogens you acquire. But you can control your daily routine, what you put into your body and how you shield yourself against germs. In recent years, scientists have begun a full-fledged push to find out which lifestyle habits actually foster a robust immune system — and which may be more hype than substance.

While the overall picture of how diet shapes immunity is still blurred, new studies do hint at the immune-strengthening effects of certain types of foods. Garlic, for instance, contains a sulfur compound called allicin, which spurs production of disease-fighting immune cells like macrophages and lymphocytes in response to threats.

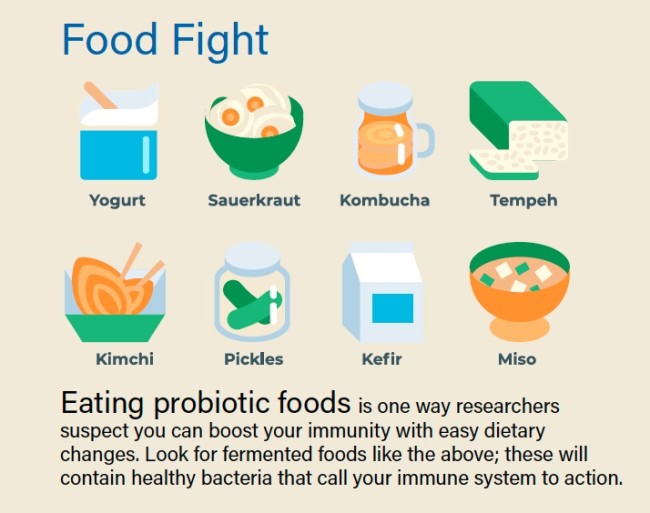

(Credit: Lucky_Find/Shutterstock)

Researchers also report that specific bacteria-containing foods — such as sauerkraut, kimchi and kefir — produce an immunologically active substance called D-phenyllactic acid. This acid appears to signal immune cells, called monocytes, to report for duty by binding to a receptor protein on the cells’ surfaces. When people eat sauerkraut, “very soon afterward, we see in the blood that there’s an increase in the level of this substance,” says Leipzig University biologist Claudia Staubert. In future studies, she hopes to clarify exactly how the acid affects monocytes’ activity in the body.

In addition to tweaking their diets, many titans of immunity embark on intense exercise regimens to keep their health robust. “I swim and snorkel year-round in the ocean, up to a mile at a clip, from New England to Miami and a few secluded points in between,” says Baron Christopher Hanson, a business consultant who claims he almost never gets sick. But so far, scientific proof that exercise improves immunity is limited. While a new study in rats shows that regular exercise changes the prevalence of different types of immune cells, it isn’t clear whether these changes make you less likely to get sick.

Getting your daily quota of shut-eye, however, does seem to boost your immunity. Repeated studies show that sleep revs up your immune response, and a recent one from Germany’s University of Tubingen reports that it does so in part by preparing disease-fighting T cells to do their jobs more effectively. That’s because your body churns out more integrins — proteins that help T cells attach to germ-infected cells and destroy them — while you’re asleep.

But while getting more sleep could help snap your streak of winter colds, squirting your palms with hand sanitizer may not. In numerous studies, plain old soap and water was shown to kill germs better than sanitizer does. “Hand sanitizer is great for alcohol-susceptible bugs, but not all bugs are susceptible,” Mellors points out. What’s more, using sanitizer won’t have any lasting effects on your immunity. The moment you touch another germy surface, your thin layer of protection will vanish.

Getting plenty of sleep is one way to boost your immune health: The body preps disease-fighting cells while you’re asleep. (Credit: Realstock/Shutterstock)

Striking a Balance

Champions of immunity tend to credit their daily habits with keeping them healthy. But many have also lucked into an ideal balance between effector T cells, the frontline immune soldiers that fend off pathogens, and regulatory T cells, which keep the body’s immune arsenal in check so it won’t over-respond to threats. An overactive immune system can be just as troublesome as an underactive one — autoimmune conditions like rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis and allergies all stem from an immune response that’s too forceful and sustained.

Last year, scientists at Kyoto University in Japan and elsewhere described one potential way to redress this kind of imbalance: turning effector T cells into regulatory T cells in the lab. Autoimmune episodes “are triggered by antigens binding to [a] receptor on effector T cells,” says molecular biologist Shuh Narumiya, one of the paper’s authors. When Narumiya and his colleagues used an inhibitor chemical to block an enzyme that controls cell development, cells that would normally develop into effector T cells turned into regulatory T cells instead — a tweak that dialed down harmful autoimmune responses in mice.

While not everyone needs such immune fine-tuning, some people could potentially benefit from a treatment based on this technique, Narumiya says. Filling out the ranks of regulatory T cells could someday help keep a range of disabling autoimmune conditions under control.

Regardless of your T cell balance or your immune track record, there’s a hefty dose of serendipity involved each time your immune system faces a threat. You might consider yourself forever prone to the flu or sniffles, but an X-factor — a cross-country move, a dietary tweak, a new therapy — can unexpectedly realign things and boost your immune potential.

By the same token, no matter how stalwart your HLA gene arsenal, how sound your sleep or how scrupulous your hygiene, you can end up knocked flat with a nasty bug when you least expect it. Immune health “is like a gigantic roulette wheel. You throw the ball down and where it lands is a matter of chance,” Mellors says. “You have an encounter with a pathogen, and at the time you get exposed, your front line is not up to snuff.” Even titans of immunity can have Achilles’ heels — and even immune systems that seem licked at the beginning can pull off unlikely victories.

Who Gets Sickest From COVID-19?

It’s a recurring theme of the COVID-19 crisis: Those infected with the virus develop vastly different symptoms. Some barely feel anything — a scratchy throat, if that — while others spend weeks in the ICU with ravaged lungs, unable to breathe on their own. This wide variation in how people respond to SARS-CoV-2 stems, in part, from each person’s unique genetic and lifestyle factors that affect their immune function.

(Credit: Andrii Vodolazhskyi/Shutterstock)

Genes

Scientists in Sydney and Hong Kong have found a particular gene variant tied to high rates of severe symptoms of SARS, a coronavirus related to the one that causes COVID-19. Because the novel coronavirus only recently appeared in humans, we don’t know exactly which genetic quirks might make us more susceptible to it. Scientists are now investigating whether other specific genes might give some people higher or lower degrees of protection against the virus.

Age and Immune Health

In some older people, or in those who have underlying immune deficits from chronic conditions, regulatory T cells — which usually keep immune responses under control — do not function normally. When these people get COVID-19, so-called cytokine storms may cause excessive inflammation in the lungs, leading to life-threatening symptoms. A study conducted by researchers in China found that COVID-19 patients with severe illness had lower levels of regulatory T cells in their bloodstream. Children may be less prone to disabling symptoms because their immune systems are better regulated and they have fewer underlying conditions.

Smoking Habits

SARS-CoV-2 uses a cell surface receptor called ACE2 to enter the cells that line your respiratory tract. New research shows that in smokers, these receptors are more preva–lent in the lungs, creating more potential access routes for the virus. “If you smoke,” says Boston Children’s Hospital immunologist Hani Harb, “the virus will be able to enter more cells in higher numbers.”

Elizabeth Svoboda is a science writer in San Jose, California. Her most recent book is The Life Heroic: How To Unleash Your Most Amazing Self.