What is the key to creativity, and how does it help our mental health? Beverley D’Silva speaks to Artist’s Way author Julia Cameron and others about ‘flow’, fear and curiosity.

C

Creativity, according to Maya Angelou, is a bottomless pit: “The more you use it, the more you have,” said the novelist. “Creativity is intelligence having fun,” is a phrase often attributed to Einstein. While advertising supremo David Ogilvy came at it from a business perspective: “If it doesn’t sell, it isn’t creative”. We know creativity is alive in all fields of life, from medicine to business and agriculture. But the word – which derives from the Latin creare, to make – is most often associated with the arts and culture, and is believed to have first appeared in the 14th-Century literary work, The Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer.

More like this:

– Three ideas for how to live your best life

– Why change is the key to a good life

– How rest and relaxation became an art

“Creativity is the natural order of life. Life is energy – pure creative energy,” is the first of 10 basic principles to be found in Julia Cameron’s bestselling creative guide, The Artist’s Way. It is subtitled A Spiritual Path to Higher Creativity because, she tells BBC Culture, “creativity is, to my eye, a spiritual experience”. For Cameron, there is no “creative elite”; we are all creative, she says. And while she began life as a scriptwriter – and continues to write novels, poetry and songs – it has become her life’s work to teach the many thousands from all creative fields who come to her artistically hampered by the demons of self-doubt and self-criticism, or claiming lack of time or talent.

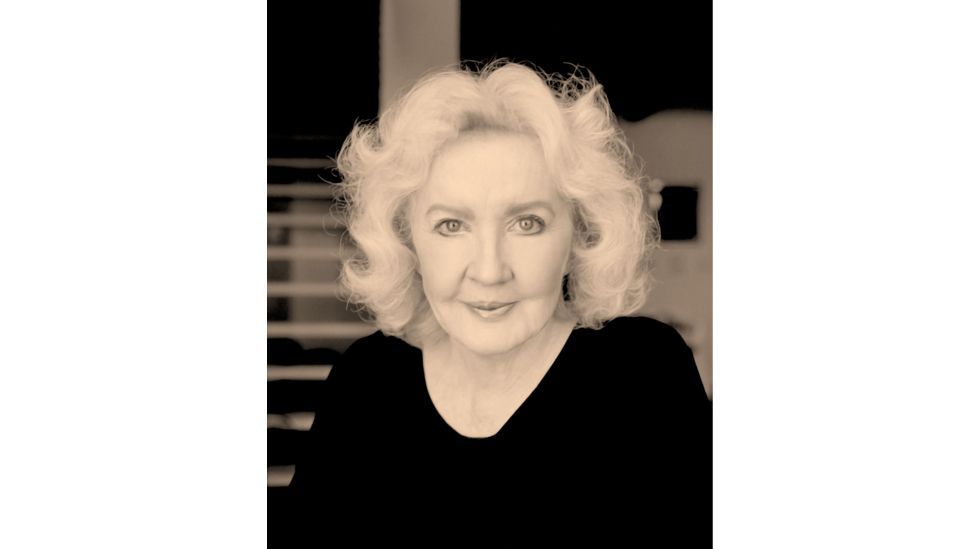

Julia Cameron’s new book The Listening Path explores “creative unblocking” (Credit: Ruth Killick)

“Many blocked people are very powerful and creative personalities who have been made to feel guilty about their own strengths and gifts,” she says. Her “bedrock of creative recovery” prescription is to write “morning pages” – three pages of stream-of-consciousness longhand writing accomplished on rising, “when our rational, self-editing mind gets out of the way of intuitive inclination”. The pages “develop our creativity and encourage belief in our potential,” she says. “They are non-negotiable.” “The artist date” is her second tool; a weekly experience to thrill, that “woos your inner artist”, such as a visit to the zoo or buying crayons.

Cameron’s new book, The Listening Path: The Creative Art of Attention, revisits those two tools, and adds walking “to induce ‘aha’ moments of insight”. The book focuses on listening – to others, yourself, the environment, your ancestors, silence. “People were always asking me how do I continue to be so prolific, and my answer is, I listen – and I ‘hear’ what I should be doing next.” The author’s own listening powers have become more attuned since relocating 10 years ago from the “honking, sirens and whistles” of Manhattan to a mountain village above Santa Fe where “it’s so quiet, I can hear a truck rumbling on the road a quarter of a mile away”.

Intuition and “guidance” which “comes from inside” have helped her stay sober since she was 29, following battles with alcohol she has been candid about. Without sobriety, she says, she would have had to kiss goodbye to creativity. It is no coincidence the Artist’s Way is a 12-week system of “recovery”, in the same way Alcoholics Anonymous follows a 12-step programme of recovery, and also addresses a spiritual lack.

Cameron tells how she was “messaged” in her 20s, on being sent by Playboy to interview the then-budding film director Martin Scorsese over lunch: “I heard a voice say: ‘This is the man you’re going to marry.’ I thought – does he know this?” He soon did. They were married (albeit briefly), and had a daughter, Domenica, now 46, a film director who has faithfully written “morning pages” since her mother came up with the idea.

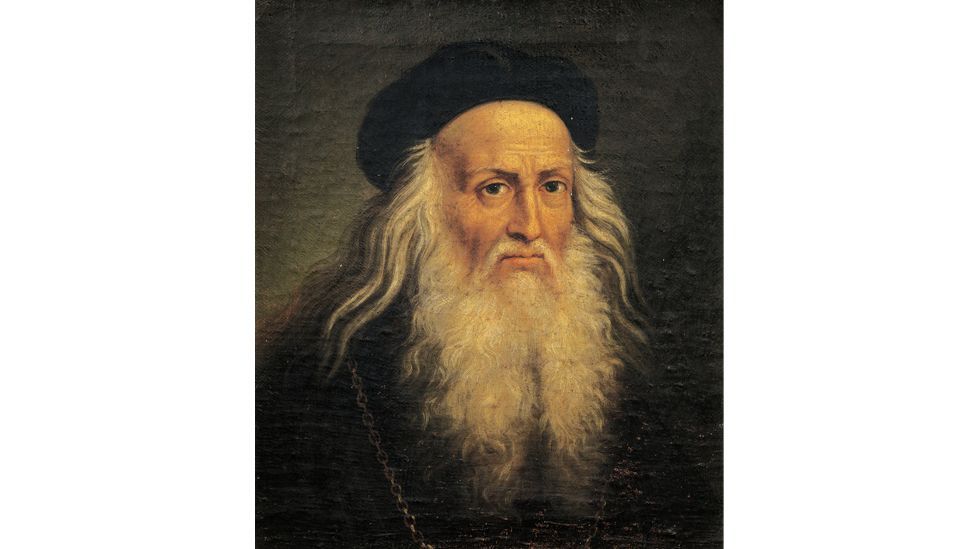

Being endlessly curious was the key to the creative genius of Leonardo da Vinci (Credit: Getty Images)

One inner voice you don’t want to pay attention to is the “inner critic”. Cameron knows hers well – he even has a persona – Nigel is a British interior designer “for whom nothing is ever good enough”. She’s wrestled him out of earshot, to publish 40 books, and write songs and musicals despite having been pigeonholed the “non-musical person” in her family. “When I teach creative unblocking, I get unblocked myself,” she says, on why she continues to teach into her 70s, and to create work, with no plans to retire.

The writer Elizabeth Gilbert acknowledges Cameron’s influence on her, saying “without the Artist’s Way there would have been no Eat Pray Love”, referring to her 2006 memoir that has sold 12 million copies.

Gilbert explored creativity in her 2015 book Big Magic: Creative Living Beyond Fear. She was inspired to write it having met so many people who complained they were creatively blocked. Their main problem, she concluded, is “always and only [to do with] fear – tumbling piles of fear”. “Creativity will always provoke your fear,” says Gilbert, who has come to terms with her own artistic anxiety by “talking to it in a friendly way… I acknowledge its importance and I invite it along”. Equally, we should allow, or even embrace, our mistakes. Being imperfect is fine. Perfectionism is “the murderer of all things good” she says.

Go with the flow

The freedom to make mistakes, especially at a young age, is vital to creativity, according to the late Sir Ken Robinson, a leading force in creative and cultural education. Robinson’s TED talk, Do Schools Kill Creativity? is the most watched video in TED’s history. “We know that if you’re not prepared to be wrong, you’ll never come up with anything original,” he said. He bemoaned the fact we often “get educated out of creativity”, seeing it as a failure of the education system.

It was an advertising executive from Buffalo, New York, Alex Osborne, who is often cited as a pioneer teacher of creativity. Osborne, aka the “father of brainstorming” developed the Creative Education Foundation in the 1950s and 60s, with Sid Parnes. Teaching “creativity problem solving”, or CPS, their model followed four basic steps: clarify, ideate, develop, implement. It begins with two assumptions: everyone is creative in some way, and creative skills can be learnt and enhanced.

Following in their footsteps, Dorte Nielsen has dedicated her life to “help others become creative thinkers”. Having worked in advertising in London in the 1990s, Nielsen returned to her native Denmark to establish the Centre for Creative Thinking in Copenhagen, and to set up a degree programme for art directors and conceptual thinkers.

“Creative thinking is like any other skill in life. The more you practise, the better you become,” Nielsen tells BBC Culture. Author of several books about creativity, her most recent is The Secret of the Highly Creative Thinker: How to Make Connections Others Don’t. It’s a boot camp for enhancing creativity, featuring exercises to inspire creative thinking and connections.

Picasso was a master of creative connections – his Bull’s Head sculpture was fashioned from a bicycle’s saddle and handlebars (Credit: Getty Images)

“Highly creative people are good at seeing connections,” she says. “By enhancing your ability to see connections you can enhance your creativity.” She cites the example of Picasso encountering a bicycle, and reimagining the seat and handlebars to create his 1942 sculpture Bull’s Head – described by art historian Roland Penrose as an “astonishingly complete metamorphosis”.

What part does the creative muse play? In Picasso’s mind, there is no point waiting for her to show up: “Inspiration exists, but it has to find you working,” he said. Novelist Isabel Allende echoed that with her advice: “Show up, show up, show up”. Meanwhile, Frida Kahlo declared: “I am my own muse. I am the subject I know best”.

Others believe we can encourage connection for inspiration, which Cameron calls “spiritual electricity”, the source, or “the flow”, the term coined in a 1990 book by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi to describe being totally absorbed in a creative activity.

The Colombian artist Dairo Vargas believes this is so. He uses “flow” techniques to make his abstract-expressionist paintings, some of which were recently displayed at London’s Royal Academy of Arts. Vargas champions mental-health awareness, and has found respite from depression in painting. Young children are naturals at “flow”, he says, and make art effortlessly and without inhibition.

Work by the artist Dairo Vargas – who champions mental health awareness – was recently displayed at London’s Royal Academy of Arts (Credit: Royal Academy of Arts)

“When we are small we are happy painting and creating because we are emotionally free,” Vargas tells BBC Culture. “With a few lines, children tell so many stories.” When he works with adults, he finds meditation helps them to “connect to a higher energy. Close your eyes, breathe, all the information you need is there”.

For others, being creative is like brushing our teeth, a daily necessity. Writing in Light the Dark: Writers on Creativity, Inspiration and the Artistic Process (edited by Joe Fassler), novelist Mark Haddon says that it is like “coming to terms with borderline pathological obsession, an activity I simply have to do to feel human”. While Amy Tan, author of The Joy Luck Club, wrote that, for her, creativity and writing is about “being open… to new ideas, other frameworks, and dates I don’t understand at first”.

When she turned 60, in 2012, she spent a week on a remote island, and was mesmerised by the world underwater. “I even saw sharks! The ocean became a play land and I thought – how could I miss this enormous world? [It] was a metaphor for how in life, in work, there can be huge openings you don’t even anticipate.”

Creativity is many things. It is making connections, with yourself or a great other “universal source”, connections that create new ideas; it is embracing fear and the inner critic; it is staying open-minded. But if Walter Isaacson’s hunch is correct, creative cleverness is nothing without an inquiring mind. Isaacson, author of a 2017 biography of Leonardo da Vinci that was based on more than 7,000 pages of the artist’s workbooks, was asked by National Geographic what made Leonardo a genius. He identified the Italian Polymath’s broad skillset – as artist, architect, engineer, and theatrical producer – as vital to his incredible achievements.

But his standout quality, he says, was his curiosity. “Being curious about everything… It’s how he pushed himself and taught himself to be a genius.” He concludes: “We will never emulate Einstein’s mathematical ability. But we can all try to learn from, and copy, Leonardo’s curiosity.”

The Listening Path: The Creative Art of Attention by Julia Cameron is published by Souvenir Press/ Profile.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.