The frozen kingdom of Antarctica may appear featureless from above, but beneath all that ice lies a mysterious and complex world that researchers say could be pivotal to understanding the effects of climate change.

It’s well established that the Antarctic ice sheet has been rapidly losing mass. As ocean temperatures have risen, the glaciers that make up the ice sheet are melting at a rate six times faster than that of 40 years ago. NASA reports that Antarctica is now losing 252 gigatons of ice per year — about three and a half Olympic swimming pools per second.

According to the National Snow and Ice Data Center, if all of Antarctica’s ice were to melt, global sea levels would rise by 200 feet, flooding every single coastal city, and wiping whole countries completely off the map. Even a more modest change in sea level would be disastrous. For example, just a 5-foot change in sea level would be enough to cover an area the size of Denmark. In the U.S., for cities such as New York City and Miami, with infrastructure very close to sea level, it would mean millions losing their homes.

But scientists have begun uncovering the features of a key factor that influences how fast Antarctica melts: an ancient continent twice the size of Australia, deep below the ice sheet.

The 1.3-mile-thick ice sheet that’s accumulated in Antarctica over the eons covers 98 percent of the southernmost continent. But for almost 100 million years, the continent lay over the South Pole without freezing. It had a much warmer climate and was covered in lush rainforests similar to those that exist in New Zealand today, with dinosaurs foraging in the abundant vegetation.

Then, about 34 million years ago, a dramatic shift in climate happened at the boundary between the Eocene and Oligocene epochs. The warm greenhouse climate became dramatically colder, creating an icehouse at the poles that has continued to the present day.

Antarctica today is divided into three regions: East Antarctica, West Antarctica and the Antarctic Peninsula, with each section comprising a different topography beneath. The ice of the Antarctic Peninsula, for example, hides a spine of mountains projecting northwest from the inside of the continent.

East Antarctica, the largest sector, includes some flatter plains as well as mountains. Here, the Gamburtsev Mountain Range — spanning 750 miles with peaks topping 11,200 feet — is about the same size as the European Alps, and completely covered by more than 2,000 feet of ice.

West Antarctica’s ground is almost entirely below sea level. The ocean bowl under the region was created during the last ice age, when the weight of the ice, much thicker at the time, pressed down on the bedrock.

The lack of landmass under West Antarctica makes the region more vulnerable to melting, as it lacks the mountain ridges that stabilize the glaciers in the east. Satellite data collected between 1996 and 2006 showed that the thinning of the ice shelves (floating sheets of ice that connect to a landmass) stagnated in East Antarctica, while in West Antarctica, the rate of the melting tripled.

In 2019, NASA created the most detailed map of the continent yet. By combining ice movement measurements, seismic data and radar images, the map — dubbed BedMachine Antarctica — revealed previously unknown topographical features, such as the broad ridges that protect the glaciers flowing across the Transantarctic Mountains, which divide East and West Antarctica.

Image:

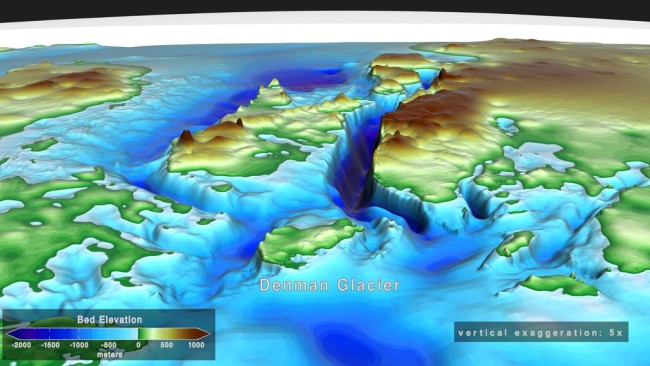

BedMachine captured the bed topography under the Denman Glacier in Antarctica, colored by the elevation. Areas below sea level are colored in shades of blue while areas above sea level are colored in green, yellow, and brown. (Credit: NASA’s Scientific Visualization Studio)

BedMachine also revealed the world’s deepest land canyon below Denman Glacier in East Antarctica, at 11,000 feet below sea level. That’s far deeper than the Dead Sea, the lowest exposed region of land, which sits 1,419 feet below sea level.

The map is an important resource that will help scientists predict precisely which regions of ice are at greatest risk of sliding into the ocean in the coming decades and centuries, and which sections might be more stable than expected.

Despite major progress in the mapping of subglacial geology, significant sections of Antarctica remain unresolved and important spatial details are missing. Understanding what’s underneath Antarctica remains crucial to foresee the ice shifts accelerated by a changing climate.