What makes an iconic book cover?

Book design has become more important than ever – but what makes an iconic jacket, asks Clare Thorp.

A

A pair of eyes and red lips floating in a midnight sky above the bright lights of New York on The Great Gatsby. The half-man, half-devil on Brett Easton Ellis’s American Psycho. A single cog for an eye on A Clockwork Orange. Two orange silhouettes on David Nicholls’ One Day. The original Harry Potter colour illustrations.

More like this:

– How bookshops are helping with isolation

– The prophetic writer who gives us hope

– How to tell other people’s stories

A great book might stay with us for a long time but, often, its cover does too. There’s a famous saying about never forming your opinion of a book by the jacket adorning it. But most readers know that we do, in fact, judge books by their covers all the time. Everything about a book’s cover – the font, the images, the colours – tells us something about what we can expect to find, or not, inside. A reader in the market for some bleak dystopian fiction is unlikely to have their head turned by a pastel-hued jacket with serif font.

F Scott Fitzgerald liked the artwork for The Great Gatsby’s 1925 cover – Celestial Eyes by Francis Cugat – so much that he wrote it into the book (Credit: Alamy)

Covers can be a swift way to signal genre, but the good ones do more than that. They give face to a book’s personality. They’re what will make you pick it up in the first place, then keep it on your shelf to remind you what it meant to you. “When you’re reading a book, it stays with you for a while, literally,” says Donna Payne, creative director at Faber & Faber. “The physical book is in your bag, in your hand, by your bedside table.”

Some books have become indelibly linked with their covers, including A Clockwork Orange by Anthony Burgess (Credit: David Pelham/Penguin Books, 1972)

The emergence of ebooks posed a threat to physical books a decade or so ago. But publishers fought back, making books that were more beautiful to look at and to hold than ever before. Fonts got bolder, colours brighter, paper more tactile. There was embossing, foil, cloth bindings and elaborate end papers. Bookshops also became spaces to spend time in, not just to shop, with books presented as objects of desire on curated table and window displays.

Alongside this – perhaps even because of it – people increasingly started posting pictures of books on social media. Search #bookstagram on Instagram and you’ll find more than 43 million images of books – next to cups of coffee, lying on crisp duvet covers, perched on the edge of sun loungers and in artfully haphazard stacks. And a medium that is all about visuals the more photogenic a book is, the more likely you are to see it all over your feed. In response to the coronavirus crisis and lockdown, the New York Public Library has even asked people to recreate their favourite book covers.

Cover art

All this means cover design is more important than ever. “I think people are really appreciating it as a form again, and designers have massively upped their game,” says Payne. But what makes a great cover? “For us, it’s one that elicits a response of some sort. It might be that not everyone loves the cover. Or it might be that everyone is talking about it. But what we don’t ever want to do is produce covers that are bland.”

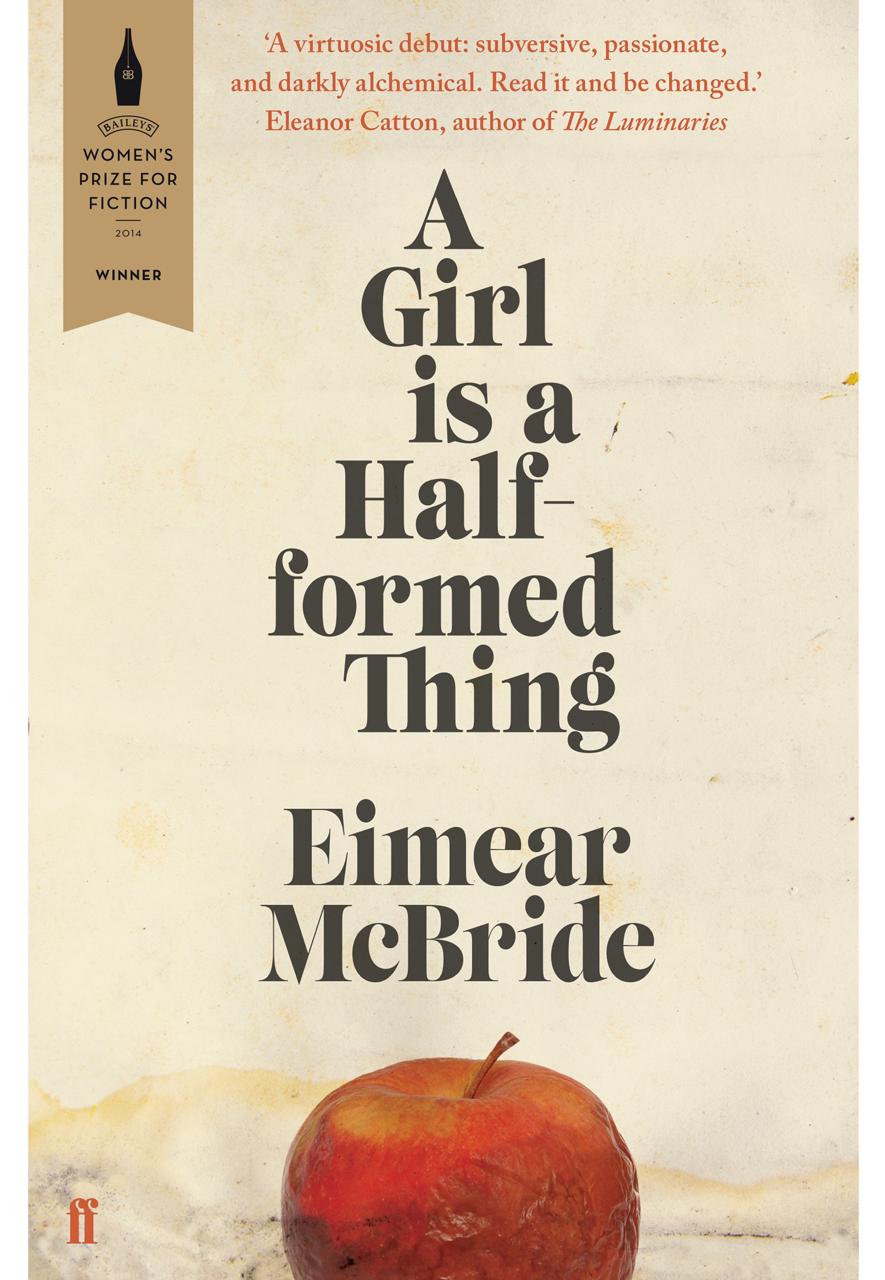

Eimear McBride’s A Girl is A Half Formed Thing is, for Payne, an example of a cover that reflects the writing inside (Credit: Faber & Faber)

A successful cover conveys something about the words inside. “If you’ve got a visceral piece of writing that’s risk-taking and bold, it’s important to put that cover on that book,” she says, citing Eimear McBride’s A Girl is A Half Formed Thing – which she designed – as an example. “The symbol of the fruit and the wet and kind of rotting paper, along with the font, just felt like it fit so seamlessly into the reading experience.”

Payne says creating a cover that is true to the book is just as important as creating something memorable. “You can publish an incredibly beautiful cover that leads you to believe it’s a certain type of book, and if that reading experience is quite different from that, it feels kind of disappointing. You’ve failed in finding the right readers for that book.”

Jon Gray, who over a 20-year career has designed covers for authors including Zadie Smith, Sally Rooney, Salmon Rushdie and David Foster Wallace, says there’s more pressure than ever to get covers right. “Bookshops are such a riot,” he says. “It’s like a big crowded party and you’re trying to get your face to stand out in the crowd. To make an impact and get someone to pick up a book and turn it over is getting harder and harder.”

It’s not just in shops that books need to stand out, but online too – whether that’s on social media or the sites people buy from – and that’s had an impact on how they look, says Gray. “Online marketing and media has led to a trend for brighter, super-saturated covers in print. The use of fluorescent and special colours and saturated imagery with white-out text. Print is being asked to match the brightness of screen.”

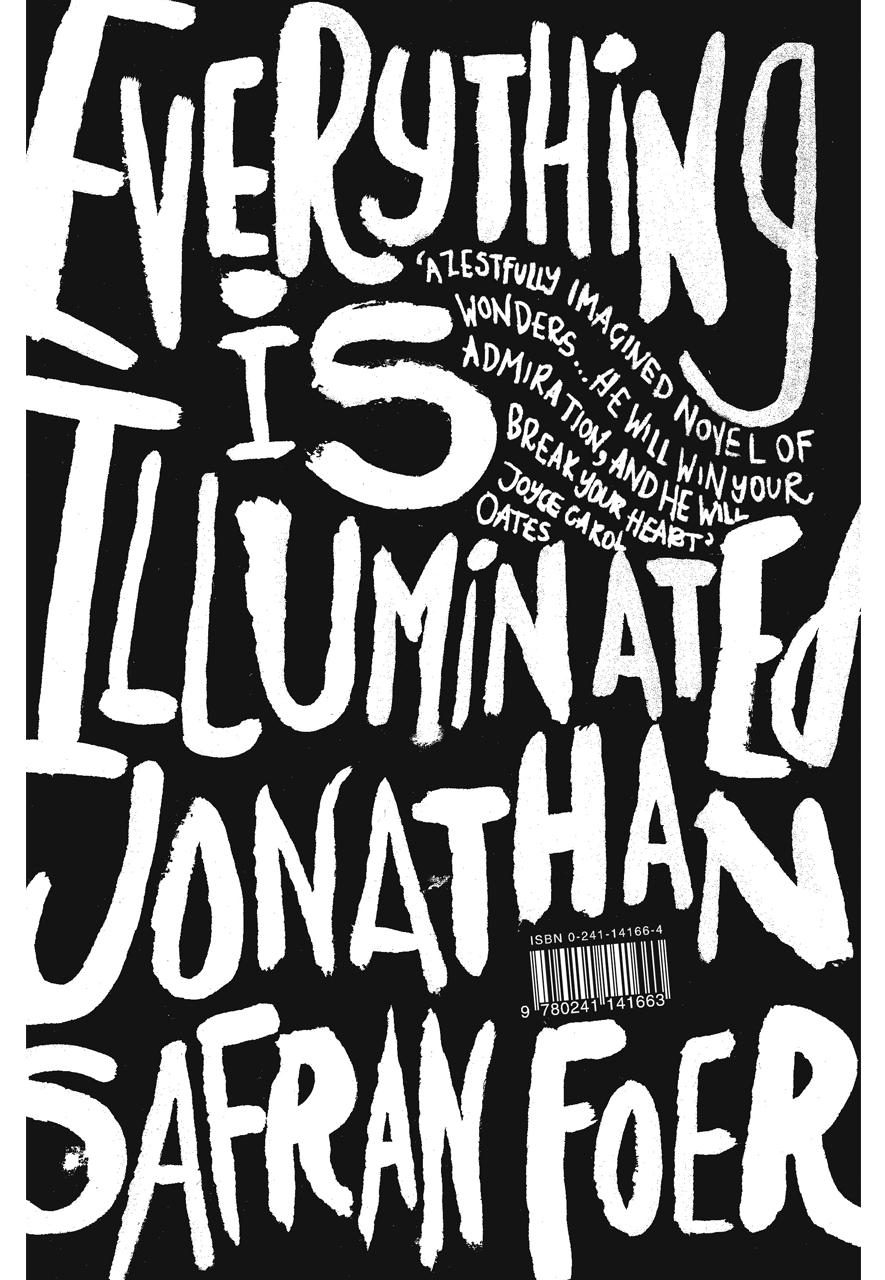

Everything is Illuminated by Jonathan Safran Foer was a creative landmark for Jon Gray (Credit: Jon Gray)

One of Gray’s early and most successful designs was for 2002’s Everything is Illuminated by Jonathan Safran Foer. “That set me on the path of doing what I do in terms of trying to get books to look like individual objects. It was the first time I really thought I want it to represent what’s inside rather than it just be some kind of statement.” The influence of Gray’s hand-drawn font is still seen on covers today – though he tries never to repeat himself. “I’m trying to make each book stand out on its own, so it doesn’t look anything else. I hope I don’t have too much of a style. I’d be really happy if people couldn’t tell I’d done a book.”

He gets manuscripts early on and reads the whole thing before coming up with ideas, to make sure he doesn’t misrepresent the text in any way. Sometimes authors have a clear idea of what they want – like Zadie Smith. “She is very visual, she’s got a very strong idea of what she likes,” says Gray. “She’ll say: ‘I’ve been looking at this’, or ‘Can we try something like this?’, give you a mood and a flavour, then give you free reign. It’s a joy to work like that.”

Vintage is marking its 30th anniversary with a series called Most Red; titles with new covers include Harper Lee’s 1960 classic To Kill a Mockingbird (Credit: Vintage)

It’s not just new books where the cover is fretted over. Increasingly, publishers are rereleasing classic books with redesigned or special edition jackets. Iconic album covers might be set in stone – but books often get several stabs at a cover. To celebrate its 30th anniversary, Vintage will republish some of its 10 bestselling books – including To Kill A Mockingbird and The Handmaid’s Tale – with new covers.

Faber have partnered with department store Liberty to publish some of their classic titles in special cloth-bound covers. Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall and Bring Up The Bodies were recently rejacketed to coincide with the release of the third book in her Thomas Cromwell trilogy, The Mirror and The Light. And Penguin Classics is set to release a science-fiction series in August – new covers featuring line drawings from artists and designers including Picasso, Le Corbusier and Herbert Bayer have been created for each of the 10 launch titles. According to Penguin art director Jim Stoddart: “Drawings have a lucid faculty to convey the innate human motive at the root of all these stories, whether experimental, humorous or chilling.” The publisher chose cover artists who, like the authors, “have developed alternative and often visionary ways of presenting reality”.

Penguin’s sci-fi classics rerelease includes The Hair-Carpet Weavers by Andreas Eschbach (Credit: cover art: Jessalyn Brooks/cover design: Jim Stoddart)

Payne claims that designing a new cover for a classic novel is also a chance to bring out an aspect of the book that hasn’t been explored before. “You have so many books published every day, it’s important to get those classic titles back on the table in front of store, and a new jacket will help to do that,” she says.

Over the past year, Gray has designed new editions of JD Salinger’s novels and a new edition of Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar, inspired by the concentric circles of Shirley Tucker’s original design. “There’s pressure to do it justice for yourself, I think. For me to do The Bell Jar, I thought I’m only going to get one go, so I want to do it right.”

Working with a well-known book brings its own set of challenges – and not just finding a new take when dozens before you have already stamped their mark. “You’re working on something that has already established itself, and people have got strong feelings about it, and you’re also working with the estates, who want to protect the legacy.” Salinger had a clause in his contract that only his name and the title can appear on the cover – no images, no quotes, no blurb.

Faber’s cover for a 2013 edition of Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar (right) drew criticism for packaging the 1963 novel as ‘chick lit’ (Credit: Jon Gray; Faber & Faber)

When a book is already much loved, any new design runs the risk of ruffling some feathers. In 2013, Faber published a 50th-anniversary edition of The Bell Jar that featured an illustration of a woman fixing her make-up in a compact mirror. It drew a mixed response, with some accusing them of trying to repackage it as ‘chick lit’, and the publisher releasing a statement defending the design, saying: “We love it, and the sales since publication suggest that new readers are finding it in the way that we hoped.”

Some books can overcome an unpopular cover. Much has been written on why Elena Ferrante’s best-selling and critically acclaimed Neapolitan novels, which chronicle the 60-year friendship between two women from Naples, have covers akin to a Hallmark card. Authors themselves aren’t always fans of their own covers. In 2015, a newly unearthed letter to her agent showed Agatha Christie hated a design for her book, Sad Cypress, calling it “common” and “awful” and asking for it to be pulped and redone.

Such staunch views just show how important book jackets are, says Payne. “It’s always lovely to hear passion. It’s always lovely to get feedback, even if the feedback isn’t all positive. If every book jacket you designed was successful every time it would mean that you never took any risks. Ultimately, disappointing jackets are those that are somehow safe.”

Jon Gray has designed covers for literary heavyweights including Zadie Smith, William Gibson and Jenny Offill (Credit: Jon Gray)

Gray has a few authors left on his design wishlist – including Iris Murdoch, John Steinbeck and Raymond Carver – but says he isn’t too precious when his own work gets rejacketed. Even so, it’s nice to see it out in the world – whether on an Instagram post or being read on public transport.

“I still get a kick out of seeing people reading books I’ve designed on the tube, or spotting it in a shop window,” he says. “Though the flipside of that is I can walk into any charity shop and see my entire back catalogue.”

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.