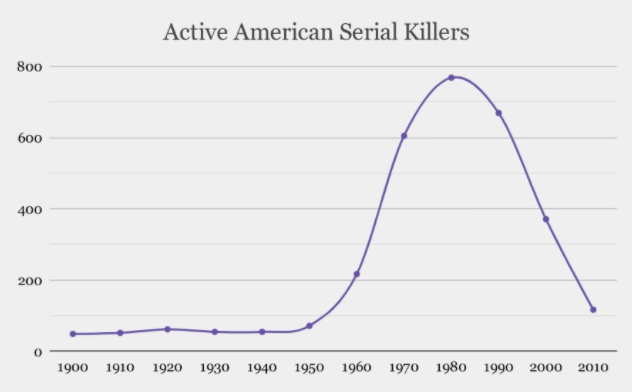

From the 1970s through the ’90s, stories of serial killers like Ted Bundy and the Green River Killer — both of whom pleaded guilty to killing dozens of women — dominated headlines. Today, however, we see far fewer twisted tales in the vein of the Zodiac Killer or John Wayne Gacy.

After that three-decade surge, a rapid decline followed. Nearly 770 serial killers operated in the U.S. throughout the 1980s, and just under 670 in the ’90s, based on data compiled by Mike Aamodt of Radford University. The sudden plummet came with the new century, when the rate fell below 400 in the aughts and, as of late 2016, just over 100 during the past decade. The rough estimate on the global rate appeared to show a similar drop over the same period. In a stunning collapse, these criminals that terrorized and captivated a generation quickly dwindled. Put another way, 189 people in the U.S. died by the hands of a serial killer in 1987, compared to 30 in 2015. Various theories attempt to explain this change.

In reality it’s not clear whether there truly was a surge of serial killing, or at least not one as pronounced as the data suggest. Advances in police investigation (for example, the ability to link murders more effectively) and improved data collection could help explain the uptick. That said, no one doubts that serial killing rose for several decades, and that rise fits with a general increase in crime. Similarly, everyone agrees on a subsequent fall in serial killing, and that, too, fits with a general decrease in crime. But where did they go?

(Credit: Data from Radford University/Florida Gulf Coast University study)

Adapting Justice

One popular theory points out the growth of forensic science, and especially the advent of genetic approaches to tracking offenders. In a recent high-profile example of these techniques, police used DNA samples from distant relatives to identify Joseph DeAngelo as the Golden State Killer, decades after he killed 12 women between 1976 and 1986. The higher prospect of capture may deter potential killers from acting out.

“Serial murder has become a more dangerous pursuit,” says Thomas Hargrove, founder of the Murder Accountability Project. “Because of DNA and improved forensics, and because police are now aware of the phenomenon, serial killers are more likely to be detected than they ever were.” The awareness he refers to begins with late FBI agent Robert Ressler, who likely coined the term “serial killer” around 1980. “There’s a power to naming something,” Hargrove says.

Many researchers also cite longer prison sentences and a reduction in parole over the decades. If a one-time murderer — or robber, for that matter — remains behind bars longer, they’ll have less of a chance to reach the FBI’s serial threshold of two kills (or three, or four, or more, depending on who you ask).

Safer Society

Would-be murderers may also have succumbed to the absence of easy targets. James Alan Fox, a criminology professor at Northeastern University, says that these days people are generally less vulnerable, limiting the pool of potential victims. “People don’t hitchhike anymore,” he says. “They have means of reaching out in an emergency situation using cell phones. There are cameras everywhere.”

Similarly, helicopter parents are more common than in generations past. Aamodt recalled his own childhood, spent walking or riding his bike unsupervised all over town. “You wouldn’t let your kids do that today,” he says. As a result, “a lot of the victims back in the ’70s or ’80s are almost impossible to find now.” The predator starves when prey are scarce.

It’s also likely that society has gotten better at detecting and reforming potential serial killers, especially in their youth. Often, Hargrove says, the early catalysts for serial murder (family dysfunction, sexual abuse) can be remedied by “quality time with a child psychologist.” He adds that pornography may quench the sexual impulses that often precede sexualized killings. “It’s possible that the sewer that is much of the internet is providing a non-violent outlet for these guys,” he says.

Yet another theory speculates that serial killers didn’t disappear, but rather transformed into mass shooters, who have skyrocketed in both numbers and prominence over the past three decades. Most experts agree, however, that the two profiles don’t overlap enough. “The motivation for a mass killer versus a serial killer tends to be different,” Aamodt says.

Hidden Killers

Serial murder is rare, comprising less than 1 percent of all homicides in the FBI’s estimate. With the annual homicide rate hovering around 15,000 in the U.S., that equates to fewer than 150 serial murders a year, perpetrated by perhaps 25 – 50 people. Aamodt’s data place the rate well below that. But considering the limitations of forensic science, many believe this is an undercount.

Police only make an arrest — or “clear” a case, in justice jargon — in about 60 percent of all homicides. The other 5,000 end without closure. In other words, murderers have a 40 percent chance of getting away with murder. The question is, how many of those unsolved cases are the work of a serial killer?

Hargrove, who argues that America does a shoddy job of accounting for such cases, set out in 2010 to write an algorithm that would analyze them in an effort to detect serial killers. Essentially, the computer code searches for similarities among murders that detectives may overlook. “We know that serial murder is more common than is officially acknowledged,” he says. And serial offenders may be responsible for an outsized portion of the unsolved cases because, by definition, “serial murders tend not to be solved. They’re good at killing.” Hargrove has estimated that as many as 2,000 serial killers, dating back to 1976, could remain at large.

But an algorithm, like an organic brain, struggles when confronted by a dataset without a pattern. Intentionally or not, many killers vary their tactics, targeting people of different races and genders in different locations. With no way to draw comparisons between these seemingly unconnected cases, computers and humans alike are helpless to link them. “Even today,” Fox says, “it’s a challenge.”

Sensationalized in Culture

For years the popular media and even some academic researchers declared that serial murder claimed, on average, 5,000 victims each year in the U.S. Fox says that figure is grossly misleading, based on the false assumption that any homicide with an unknown motive — of which there are about 5,000 annually — is the work of a serial killer. Fox estimates that even in the 1980s the real number was actually fewer than 200, and Aamodt’s data supports this.

Regardless, those sensational claims enthralled the nation, and the world. And today, though their ranks have shrunk, serial killer fascination does seem to be returning. In the 2019 film Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile, Zac Efron plays the infamous Ted Bundy. In the Mindhunter series, which aired in 2017 and explores the origin of criminal profiling in the FBI, one of the two lead characters is based on aforementioned agent Ressler. But Fox points to a curious caveat: “They’re focusing on all the cases of yesteryear.” Culturally, we’re still talking about killers who were active decades ago, and few in the modern age have become household names.

Serial killers are still with us, though, even if they’re less common. And barring major advances in our ability to catch them, we cannot fully grasp their magnitude. As Hargrove put it, “Only the devil knows.” That uncertainty, in its own way, can chill the spine as much as any known killer’s dark deeds.