In 48 B.C., as Cleopatra plotted to regain power amid a civil war with her brother, the Roman historian Cassius Dio wrote that Egypt’s last pharaoh “reposed in her beauty all her claims to the throne.” She arranged a meeting with the Roman dictator Julius Caesar — a man notorious for his affairs with noblewomen — to ask his help. In Dio’s telling, the encounter vindicated her vanity: Caesar was, apparently, “so completely captivated” by the young woman that he agreed to reconcile the warring siblings.

It’s a familiar trope: the queen of the Nile, a cunning charmer, deploying her supreme loveliness like a political weapon. Indeed, it defines our perception of Cleopatra even today. Her portrayal in film — epitomized by Elizabeth Taylor’s 1963 performance — is that of a buxom, sultry femme fatale, her steamy eyes wing-tipped and her raven hair falling lushly around her shoulders. She reclines sensually in revealing gowns. She greets her Roman lovers, Caesar and Mark Antony, with palpable, barely suppressed passion.

Such characters play well on screen. But based on the few surviving clues to Cleopatra’s actual appearance, modern historians doubt she resembled this caricature. They also doubt she ruled exclusively by means of physical beauty and sexual prowess, like the “whore queen” her Roman enemies made her out to be.

Throughout history, female rulers have often been accused of using their sexuality to maintain control. Historians recognize this as the concept of the whore queen; for example, after Mary Stuart fell from power in the 1500s, as she was being led to prison, a crowd of disenchanted Scots cried, “Burn the whore!” The Romans tried a similar tactic with Cleopatra. Their smear campaign shaped a legacy, founded upon her looks, that still fascinates us two millennia later.

Cleopatra’s Many Faces

Scholars have searched for the visage behind the legend, but it’s often impossible to verify a historical figure’s image. Cleopatra’s body has never been discovered. Most surviving paintings and sculptures of her are anachronistic inventions, more telling of their own times than of the subject herself. Even contemporary works can deceive, says Egyptologist Robert Bianchi, overlaid as they are “with political or ideological concerns.”

In short, Bianchi says, for Cleopatra “there is nothing that approaches the Western concept of a portrait in either ancient Egyptian or ancient Greek art.” But there are some potential leads. Among the most promising are coins minted during her reign — portrayals that are far from Hollywood’s glamorous visions.

No two coins are quite alike, but in many, the most prominent features are an aquiline nose and a jutting chin. She wears her curly hair not in bangs but in the popular melon style of the time, tied in a bun at the base of her skull. Even these coins come with red flags, though. During her marriage with Mark Antony, a silver denarius coin was issued to pay his troops. Each side of the coin bears one of their faces, and hers seems exaggeratedly Romanized to match his.

A coin from Antony and Cleopatra’s alliance, dated to 37-33 B.C., and minted in the Eastern Mediterranean (possibly Antioch, Syria). Cleopatra’s image appears on the front of the coin, which signals her greater importance. (CC-0 Public Domain Designation/Art Institute of Chicago)

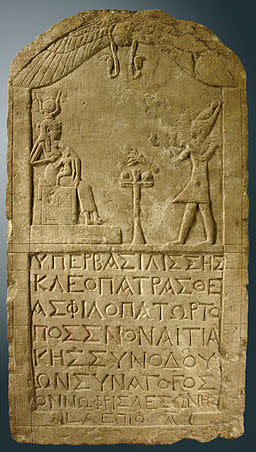

The only other unambiguous representations of Cleopatra are Egyptian reliefs in the pharaonic style — designed, perhaps unrealistically, for the eyes of her subjects. In these colossal stone canvases, she’s more god than human. A few late-Hellenic marble busts dating to her lifetime may depict the queen, but none are inscribed with her name. (The hair in these matches the coins, but the nose and chin are less pronounced.)

Even if these sketchy sources collectively offer some idea of her appearance, they probably can’t tell whether she was “beautiful” — whatever that means. They certainly can’t tell us what Caesar or Antony saw in her. Besides, some scholars argue, the whole preoccupation with her allure is inappropriate — no different from overanalyzing the physique of a modern female leader. “Why are we so obsessed with talking about whether she was attractive or not,” asks Egyptologist Sally-Ann Ashton, “when really we should be looking at her as a strong and influential ruler from 2,000 years ago?”

A relief depicting Cleopatra in pharaoh’s garb and presenting offerings to Isis, dated to 51 BC. (Credit: Public Domain/Wikimedia Commons)

The Queen’s Color

Cleopatra’s immense power came from her position in Egypt’s long-ruling Ptolemaic dynasty. The question of her appearance is somewhat entangled with that identity. Her family hailed not from the land it governed but from Macedonia, which has led many researchers to believe her skin was light — as European art has always depicted her — not dark like that of the native Egyptians. Some, like Cleopatra biographer Michael Grant, are adamant that she had “not a drop of Egyptian blood in her veins.”

Others point to uncertainties in her family tree. The lineage of her father, Ptolemy XII, a pharaoh himself, is well-documented; her mother’s, not so much. In fact, no one is sure of her mother’s identity, and even less so of her grandparents’. Still others note that Macedonia, along with the rest of the Hellenic world, was not exclusively white — so her European descent did not preclude blackness.

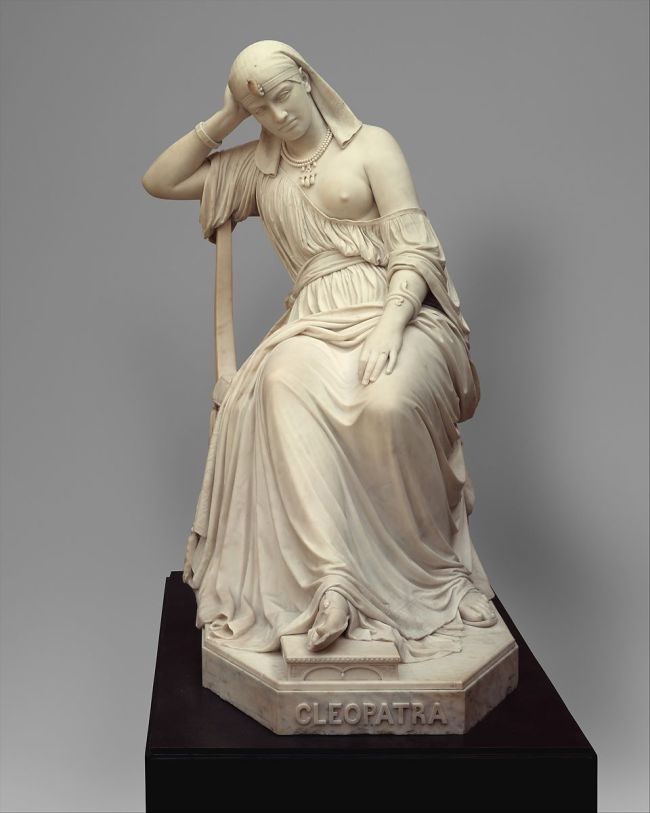

The ethnic uncertainty surrounding Cleopatra has made her into an unlikely proxy for today’s cultural debates. Most recently, the casting of Israeli actress Gal Gadot as the queen in an upcoming film met with disappointment and outrage from critics who hoped to see a woman of African heritage fill the role. But the concept of a dark-skinned Cleopatra originated much earlier, when the 19th-century artist William Wetmore Story sculpted her with black features as an abolitionist statement.

A marble carving of Cleopatra. (Credit: William Wetmore Story/CC-0 Public Domain/The Met)

To cultural historian Mary Hamer, it’s no wonder an ancient queen stands at the center of a modern battle between classicists and the Afrocentrist movement. After all, she was perhaps the worthiest adversary of a budding Roman empire, and in that way, she influenced Europe’s path to domination at the outset. When people ask whether Cleopatra was black, Hamer writes, “it seems understood that to answer in the affirmative might put the entire structure of Western civilization into question.” It would mean that, at a pivotal moment in European (read: white and patriarchal) history, the political universe revolved around a black woman.

‘An Irresistible Charm’

The final hints in the quest for Cleopatra’s countenance come from the writings of Romans in the centuries after her death, though some show obvious bias. Her reputation was largely defined by Augustus, Rome’s first emperor. After the republic’s civil war, when he needed to justify the violence he’d waged against his Roman brothers, he and his allies found a scapegoat in Cleopatra. Wanting the public to believe it was she who persuaded the virtuous Caesar and Antony to turn on their own country, they painted her as a foreign temptress. One Augustan poet and propagandist, Propertius, branded her the meretrix regina, or “whore queen.”

Later classical historians bring more impartiality and nuance, but they disagree on Cleopatra’s appearance. Cassius Dio, in his Roman History, calls her “a woman of surpassing beauty,” and adds that “when she was in the prime of her youth, she was most striking.” This fits the standard narrative. Plutarch, in his Life of Antony, is more restrained. “For her beauty, as we are told, was in itself not altogether incomparable,” he writes, “nor such as to strike those who saw her.”

A likely posthumously-painted portrait of Cleopatra, from Roman Herculaneum, Italy, dated to the 1st century AD. (Credit: Angel M. Felicisimo/Public Domain/Wikimedia Commons)

What Plutarch does emphasize is that “converse with her had an irresistible charm, and her presence … had something stimulating about it. There was sweetness also in the tones of her voice,” he writes. She spoke many languages and was talented in all the ways expected of a male ruler. According to the historian Sarah Pomeroy, she “rode horseback, hunted, and was at home on the battlefield.” Plutarch attests to her cleverness and intellect, and William Shakespeare, in his play Antony and Cleopatra, followed that lead: “She is cunning past man’s thoughts,” the bard writes.

We may never be sure of what Cleopatra looked like, but the basic facts of her life are clear. As Ashton says, “I’d rather look at the hard evidence.” She wielded as much power as nearly anyone in the ancient Mediterranean and ruled over one of its greatest kingdoms. Augustus may have molded her story, but this implies he considered her a threat grave enough to warrant his slander.

It seems he also inadvertently helped to secure her place in eternity. After 2,000 years, for whatever reason, each generation still fixates anew on the queen, recreating her to suit its needs. “The demands of the moment have always determined Cleopatra’s image,” Hamer writes. As a result, her fame stretches ever deeper into her afterlife. Shakespeare, musing more than 400 years ago, couldn’t have known how truly he spoke: “Age cannot wither her, nor custom stale / Her infinite variety.”