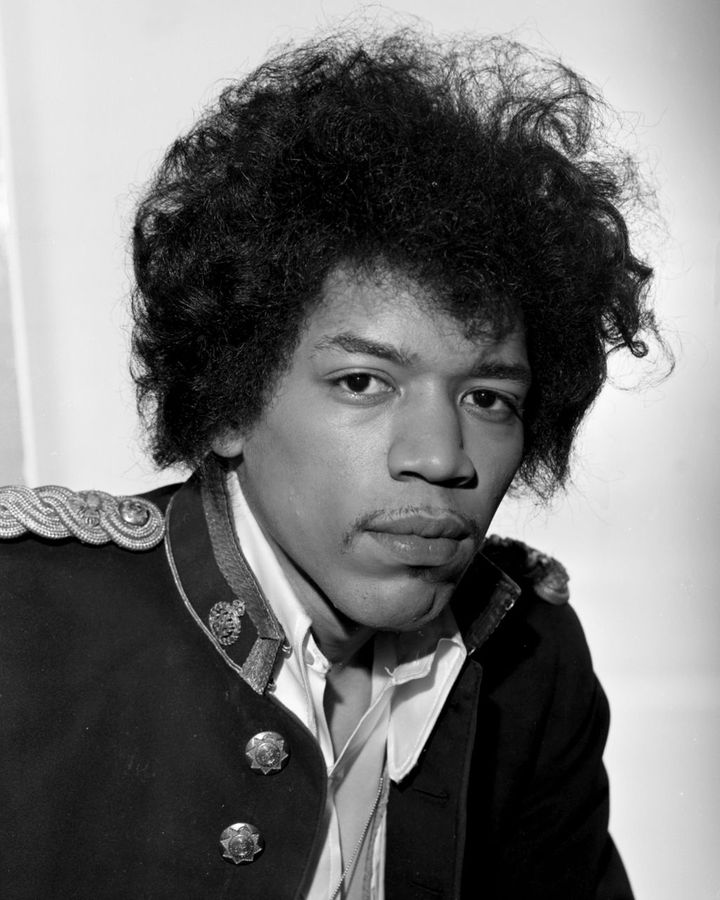

Few guitarists are treated with as much reverence as Jimi Hendrix. But myths about his talent do him a disservice, argues Greg Kot.

F

Fifty years ago today, one of the most important and influential musicians of the 21st Century, Jimi Hendrix, died. All Is by My Side, the John Ridley-directed, loosely biographical movie about Jimi Hendrix’s early life, claims to tell the story of the guitarist and musical shape-shifter as he was on the cusp of becoming an international star. The film focuses on the 1966-67 years, when Hendrix came to London and was ‘discovered’ by Britain’s rock royalty, including Paul McCartney, Eric Clapton and Jeff Beck.

This article was originally published in September 2014.

Amid the endless retellings of this tale, there is a sense that Hendrix was a Halley’s Comet of rock guitar, a once-in-a-lifetime game-changer who arrived fully formed in London, long before his ground-breaking 1967 debut album, Are You Experienced? To hear the history books tell it, that album’s arrival was akin to tectonic plates shifting, the earth moving beneath a culture’s feet. We are told that there’s guitar before Hendrix, and there’s guitar after Hendrix. Few rock instrumentalists get treated so reverently, and fewer still created their own aura and era so definitively for all time. It didn’t hurt that Hendrix died in 1970, only three years after his arrival as a seemingly instant rock star.

All is by My Side traces Jimi Hendrix’s rise to fame (Credit: XLrator Media)

All this from a man who spoke softly and did not appear to be outwardly driven by what the music business had to offer. Yet on Voodoo Chile, one of his most esteemed tracks, Hendrix channels some of the high-testosterone mythmaking of one of his idols, Muddy Waters, when he declares, “Well the night I was born/Lord I swear the moon turned a fire red.”

I’m pretty sure the moon didn’t turn a fire red on 27 November 1942, and it’s certain Hendrix knew his mythical powers weren’t created by cosmic events but by not-so-mythical virtues such as intense listening, astute taste and heavy road work. Call it a combination of blood, sweat and brains, but Hendrix was less an instant sensation than a student who, through intensive training and innate talent, transcended his many teachers. All those who buy into the Halley’s Comet myth do Hendrix and his work ethic a disservice.

‘A little science fiction’

Like The Beatles before him, who were hailed as rock ‘n’ roll saviours, Hendrix thought of himself as more of a skilful synthesist of what had come before than a whole new entity. He always said he was channelling the blues into his own thing with “a little science fiction”. In interviews, he was generous about name-checking his inspirations, and they were numerous.

Hendrix paid his dues working with bigger bands, learning innovations of groundbreaking guitarists (Credit: Getty Images)

Just as The Beatles paid their dues playing countless hours on makeshift stages in Hamburg’s red-light district, years before they donned suits and shook hands with the Queen, Hendrix was working the hard-scrabble ‘chitlin’ circuit’ of Southern dives as a hired-gun who wasn’t given much room to show off lest he outshine the artists who were paying him. He worked with The Isley Brothers – who wouldn’t have their biggest hits until years later – and Little Richard, who was trying to mount a rock ‘n’ roll comeback after years in gospel exile, and he learned how to drive a band and deliver a song economically and efficiently. Meanwhile, he was absorbing the innovations of guitarists ranging from Buddy Guy to Les Paul.

On the Isleys’ 1964 track Testify, Hendrix finds an opening for a four-bar solo in which he pays tribute to a young Guy, the Chicago guitarist who was already messing with distortion and sustain in a way that didn’t thrill his conservative bosses at Chess Records. Guy’s performances were jaw-dropping in their intensity and showmanship, drawing on the stage presence of such legends as Lightnin’ Hopkins and Chuck Berry, adding distortion and sustain while playing behind his back or even with his teeth.

Clapton and Hendrix were among those taking notes; both of their discographies are crammed with Guy quotes. Jeff Beck heard it as well, noting that Hendrix’s brilliant Stone Free, the B side of his first single, Hey Joe, fused Guy’s violence with Paul’s technical precision.

A myth worth remembering

Hendrix was also absorbing the lyrical playing of Curtis Mayfield from countless Impressions singles, as heard on The Wind Cries Mary, and all the blues masters. It’s no accident that when he first jammed with the infant Cream in 1966 it was on Howlin’ Wolf’s 1964 classic Killing Floor, while embellishing the murderous six-string licks of Hubert Sumlin.

Hendrix loved to explore and look beyond the rule book (Credit: BBC)

In sections of Foxy Lady, Hendrix sculpted feedback in a way that had been broached by guitarists such as Link Wray and Bo Diddley in the ’50s, and taken a step beyond by the Yardbirds in the ’60s. Purple Haze found Hendrix reimagining Bill Doggett’s 1958 Hold It and Duane Eddy via Henry Mancini’s Peter Gunn theme. He also was soaking up the free jazz of John Coltrane and Albert Ayler, as was apparent in the avant-garde wall of sound he built on I Don’t Live Today.

But the greatest lesson Hendrix picked up from his predecessors was more one of attitude than technique. In the hands of Guy or Bo Diddley, the guitar was a sound machine rather than an instrument with a prescribed vocabulary. Hendrix saw the possibilities outside the rule-book margins and unlike Guy, found a band, manager and record company who let him wander into the wild fearlessly. He left behind hundreds of tracks and works in progress while recording a handful of officially released studio albums, a testament to how much he loved to explore, and how difficult he was to please. He tirelessly chased the sounds he heard in his head until his death, as if he knew that was the only way to create a myth worth remembering.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.