Near the end of summer, the research vessel Polarstern found itself in an ironic — and telling — situation: As it neared an historic rendezvous with the North Pole, the German icebreaker found relatively little solid ice to break.

Although they couldn’t know it at the time, the situation foreshadowed an announcement today by the National Snow and Ice Data Center: Arctic sea ice has likely reached its second lowest extent on record, following a dramatic melt-off in early September.

Even before that large-scale melting, the Polarstern was cruising through very light ice conditions in a region above northern Greenland that’s usually covered in thick sea ice. The ship’s destination: the North Pole.

“We made fast progress in a few days,” expedition leader Markus Rex told The Associated Press. “It’s breathtaking — at times we had open water as far as the eye could see.”

Reaching the pole on August 19, 2020, the ship’s crewmembers found partly open water along with thin, weak ice covered in many places with melt ponds.

The Polarstern remained not far from the pole (about 130 nautical miles) until just yesterday, as part of the the most elaborate Arctic expedition ever undertaken: the Multidisciplinary drifting Observatory for the Study of Arctic Climate, or MOSAiC.

Onslaught of Siberian warmth

For nearly a year, MOSAiC scientists had been studying the interactions between sea ice, the ocean, and the atmosphere in order to gain a better understanding of climate change in a region that’s warming three times faster than the global mean. And as they were conducting the final phase of their work during late August and early September, warm air pouring out of Siberia began melting the ice to their south, toward Russia, at a very rapid pace.

Every day between August 31 and September 5, an area of sea ice nearly the size of Maine disappeared. This was, in fact, a greater rate of loss than had been observed in any other year during that particular six-day period.

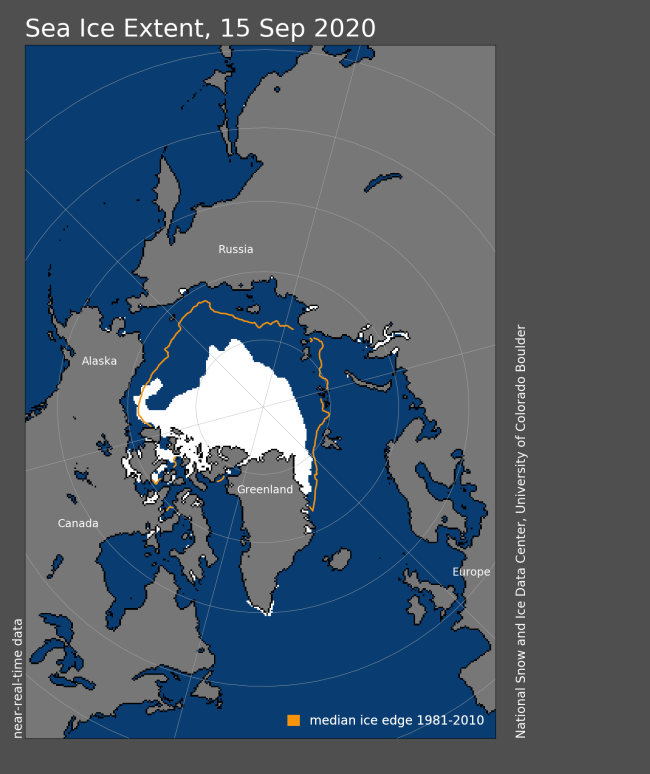

The extent of floating Arctic sea ice on Sept. 15, 2020, compared to the median ice edge, delineated by the orange line, for the period 1981-2010. There’s abut a million square miles of ‘missing’ ice. (Credit: National Snow and Ice Data Center)

The result: By September 15, 2020, the Arctic’s floating lid of sea ice had shriveled so much that only 2012 rivaled it for lowest extent ever observed during the 42-year continuous satellite monitoring record. According to the National Snow and Ice Data Center, on that date, sea ice covered 1.44 million square miles of the Arctic – a little shy of a million square miles below the long-term median coverage of ice.

That’s an area of ‘missing’ ice almost equivalent in size to the entire Western United States, which comprise about a third of the 48 contiguous states.

Since then, the arrival of autumn’s cooling temperatures have caused sea ice to expand. The NSIDC does caution, however, that “changing winds or late-season melt could still reduce the Arctic ice extent, as happened in 2005 and 2010.” So for the final word about the Arctic melt season we’ll need to wait until early October, when the center plans to release a full analysis.

Human-caused warming and other factors

September is the month when Arctic sea ice reaches its annual minimum, following the warmth of summer. Over the lung run, human-caused climate change has caused that minimum extent to decline. But what were the specific factors that contributed to this year’s particularly low extent?

In an email on Sept. 17, I asked Mark Serreze, director of the NSIDC, to characterize the nature of this year’s evolution of sea ice — from buildup to maximum and now the melt-out to minimum. Here was his answer:

“It was inevitable. The atmospheric circulation pattern last winter — a strongly positive Arctic Oscillation – left us with a lot of thin ice in spring along the Siberian Coast, primed to melt out in summer. The ‘Siberian Heat Wave‘ led to an early melt along the Siberian coast. The summer overall was warm. We knew we’d lose a lot ice, and the only question was where we’d sit in the records book at the September seasonal minimum.”

Now we know.

I also asked Serreze what he made of the open water, melt ponds, and thin ice that the Polarstern and its MOSAiC expedition crew encountered at the North pole back on Aug. 19. His answer:

“What we see in 2020 is going to be pretty typical of what we’ll be seeing in the future Arctic. We’ll probably lose essentially all of the summer ice sometime over the next 20-30 years. Combine what we’ve been seeing in the Arctic with heat waves, massive wildfires and hurricanes, and the year 2020 may go down in the annals of history as the end of all plausible denial that global warming is very real and is here in a big way.”

(Full disclosure: In addition to running ImaGeo here at Discover, I am a professor at the University of Colorado, which is home to the NSIDC. That makes me and Mark Serreze colleagues. But neither he nor the NSIDC nor the university exercise any control over my reporting.)

The Polarstern heads home

It was on September 20, 2019 that the Polarstern weighed anchor and headed north from the Arctic port of Tromso, Norway to begin the historic year-long MOSAiC mission. In early October, the ship reached the Arctic sea ice edge, and the crew then froze their ship into an ice floe.

The goal: to drift with it across the high Arctic to make scientific observations that had never been made before so far north in the dead of winter.

The atmospheric circulation pattern described by Mark Serreze wound up carrying them across the Arctic rapidly, spitting them out of the ice in July, earlier than planned. Not long after that, they decided to make their dash for the North Pole, and then to find a new floe to freeze themselves into.

Markus Rex, leader of the MOSAiC expedition, took this photo of the sun with a halo around it on Sept. 13, 2020. The rings are caused by refraction and reflection of sunlight by ice crystals in cirrus clouds. At this point, the expedition’s research vessel was frozen to an ice floe near the North Pole and was carrying out the final phase of their research before heading home. (Credit: Courtesy Alfred-Wegener-Institut / Markus Rex)

They succeeded, and it was this floe that they were attached to when warmth was pouring out of Siberia in late August, causing ice to their south to shrivel rapidly.

Then, on Sept. 20, 2020 — five days after the Arctic sea ice had reached its minimum, and eactly a year after leaving Tromso — the crew pulled up the gangway for the last time and began their journey home. (Note: Please look for Discover’s annual year in science issue, which will feature a story about the MOSAiC expedition.)

For Serreze, what was seen in the high north this year was no real surprise:

“What’s happening in the Arctic and elsewhere is in line with what climate scientists have been predicting for many years. We hate to say we told you so, but we told you so.”