No one can “predict” an earthquake. Let’s get that out first. We don’t understand enough of exactly what triggers large earthquakes to ever say with any certainty that one will strike on a specific day in a specific location. However, by looking at patterns of earthquakes in the past and swarms of earthquakes in the present, seismologists can begin to forecast the likelihood of a big earthquake. This is like weather forecasting — we know there is a chance of something happening, but by no means is it a prediction of something happening at a specific time and date.

Southern California has been experiencing an earthquake swarm near the Salton Sea for the past few days. None of the earthquakes have been big. They have mostly been in the magnitude 2-3 range with a few as large as M4.6. The smaller ones you might notice, the larger would definitely be felt, but none are widely destructive. So, where could all these earthquakes lead?

Busy Geology of the Salton Sea

The Salton Sea lies along the San Andreas Fault System, although it is a somewhat complicated area. The Sea lies in the Brawley Seismic Zone, where there is both the classic side-by-side motion (strike-slip) of the San Andreas Fault as well as pull-apart motion (extension) that makes the basin. In fact, the Brawley Seismic Zone is the northernmost piece of the Pacific Ocean spreading that extends to the southern hemisphere. North of the Salton Sea, this spreading becomes the side-by-side sliding of North America and the Pacific Plate.

This means that multiple kinds of earthquakes can happen and some of them can be large. This seismic zone has produced two major earthquakes over the past 100 years: the M6.9 El Centro temblor in 1940 and the M6.5 Imperial Valley earthquake in 1979. As recently as 2012, an earthquake swarm in the area produced earthquakes up to M5. That swarm may have been triggered by the geothermal injections done in that area.

The Salton Sea area is also home to potentially active volcanoes. The Salton Buttes are rhyolite volcanoes that lie in and along the Sea and may have erupted as recently as about 200 AD. Now, these earthquake swarms in 2012 and now are not connected to magma moving under the area, but it just shows how geologically active this area is.

Current Earthquake Swarm

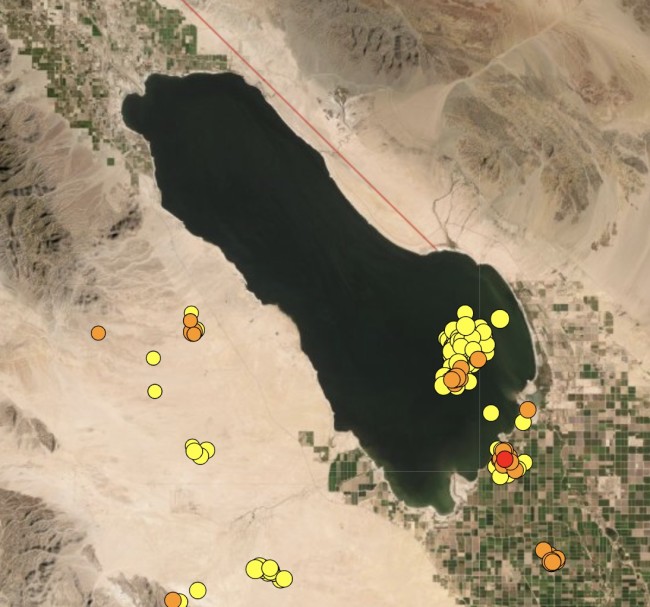

The current earthquake swarm in California’s Salton Sea that started on August 10, 2020. Credit: USGS.

The current earthquake swarm started on August 10 and has already generated dozens of earthquakes underneath the Salton Sea. These swarms aren’t uncommon – this is now the fourth of this century and they usually end in less than a month., However, this activity did prompt the US Geologic Survey to release a forecast for the potential of a large earthquake. After the first day, they forecasted an 80% chance of the swarm continuing but not producing any temblors larger than M5. This would be the typical behavior for swarms like this in the area.

However, they did say there was a 19% chance of the earthquakes in the swarm being foreshocks of a potentially larger earthquake in line with what has happened during the past 100 years. That’s not a high probability, but enough to note.

An even smaller chance exists for a truly massive earthquake larger than M7, but that was only about a 1% chance. That’s because they occur much less frequently in that stretch of southern California. Unlike the M6 earthquakes that have happened multiple times in the past century, a M7 earthquake hasn’t happened in 300 years.

The swarm has settled down a bit since its opening day, so the USGS has revised its initial estimates. Now they think that it is a 98% chance that the swarm continues much as it is going now and has dropped the chance of a large earthquake down to 2% (and very large to <1%).

This is no guarantee, but with new data comes a new forecast. Think of this like trying to forecast how strong a hurricane might be when it makes landfall — new information about the winds and barometric pressure lead to a new forecast. For earthquakes, the changing frequency and size of the swarm might hint at new probabilities.

We’re still in the infancy of earthquake forecasting. The most important thing you can take away from all this is that if you live in one of these areas, you should always be prepared for the next big earthquakes. Earthquakes can happen almost anywhere in the country — just look at Sunday’s M5.1 in North Carolina — but we can be prepared for their impact.