The extraordinary story of the legendary beauty Lizzie Siddal is both surprising and tragic, and led to a strange myth that persists today. Lucinda Hawksley explores her legacy.

I

In the winter of 1849-1850, the artists Dante Gabriel Rossetti and William Holman Hunt were painting together, when their friend Walter Howell Deverell burst into the studio. The visitor announced excitedly, “You fellows can’t tell what a stupendously beautiful creature I have found… She’s like a queen, magnificently tall.” With these words, the unlikely beauty of Elizabeth Siddal began to make history.

This story was originally published in January 2020

More like this:

– The lost portrait of Charles Dickens

– Can joy exist without sadness?

– The greatest visionary in 200 years

Today, few people remember the artist Deverell – who died of Bright’s (kidney) disease at the age of 27 – but he was a vibrant member of the group of artists and writers that revolved around the newly formed Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. This secret society of seven young men had been founded in 1848 by Rossetti, Holman Hunt and John Everett Millais, students at London’s Royal Academy. As is being highlighted in the National Portrait Gallery’s exhibition, Pre-Raphaelite Sisters, the Pre-Raphaelite movement also encompassed female models, artists and writers. ‘Lizzie’ Siddal began as a model, then learnt to paint, and also wrote poetry.

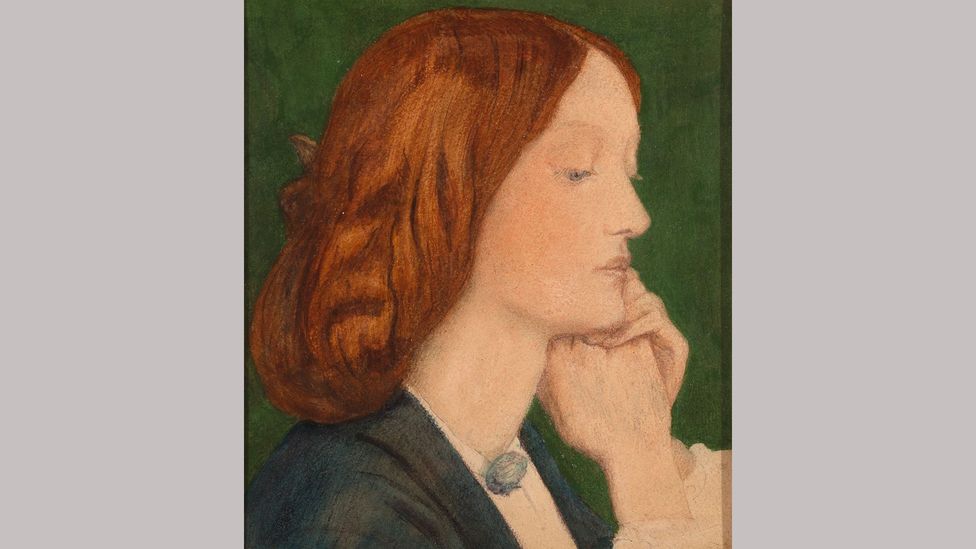

Elizabeth Siddal by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1852, is one of the paintings on display at an exhibition at London’s National Portrait Gallery (Credit: Delaware Art Museum)

At the time of Deverell’s pronouncement, Siddal was working at a milliner’s shop, near Leicester Square, in central London. She worked long hours in unpleasant conditions, and her family was worrying about her already delicate health. Perhaps this was why Siddal’s mother made the surprising decision to permit her daughter to work as an artist’s model – something viewed as disreputable, and even as synonymous with prostitution. Deverell did not dare approach Lizzie’s mother himself. Instead he sent his own very respectable mother, in her grand carriage, to talk about the finances. Mrs Siddal was awed by the arrival of a carriage at her modest home on the Old Kent Road.

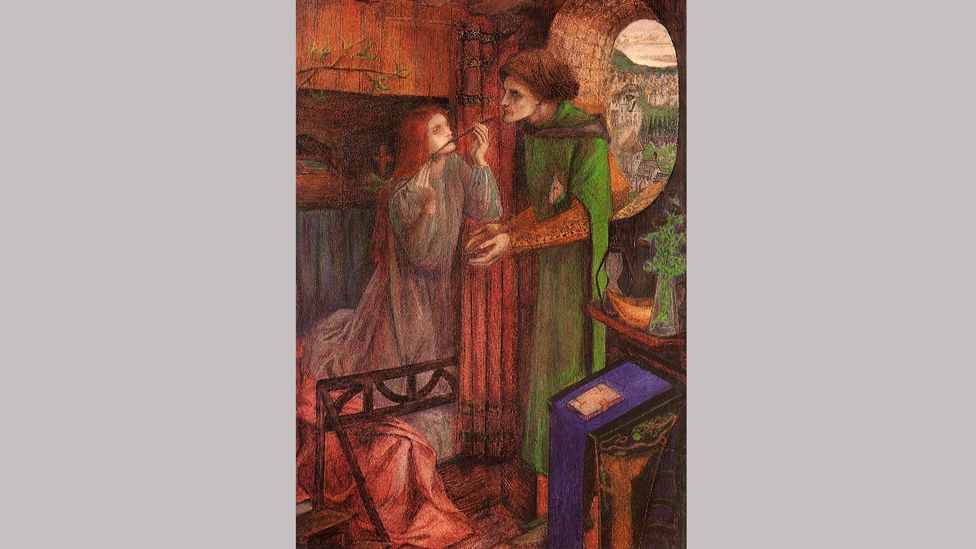

Initially, Siddal started working part-time as a model, and remained part-time at the hat shop. After Deverell painted her as Viola in Twelfth Night, Holman Hunt painted her for A Converted British Family Sheltering a Christian Priest from the Persecution of the Druids (1850), and as Sylvia in Valentine Rescuing Sylvia from Proteus (1850-1851). She modelled for Rossetti for the first time in 1850, for one of his lesser-known paintings, Rossovestita.

‘Like a queen’ is how Walter Howell Deverell described Lizzie Siddal – she was the model for Viola in his painting Twelfth Night (c.1850) (Credit: Alamy)

According to his patron, John Ruskin, throughout their ensuing relationship, Rossetti drew and painted Siddal thousands of times.

Although today Lizzie Siddal’s willowy build, gaunt features and lustrous copper-coloured hair are considered signs of beauty, in the 1850s being very thin was not considered sexually attractive, and red hair was described by one female journalist as “social suicide”. Through her modelling work and the success of the paintings she appeared in, Lizzie helped change the public opinion of beauty.

Within a couple of years, Lizzie was earning enough to leave the hat shop. As the model for Millais’s celebrated Ophelia (1851-1852), her face became famous. Other artists clamoured to paint her, but Rossetti, by this time recognised as her lover, became jealous and asked her to model only for him. Charles Allston Collins (younger brother of Wilkie Collins) recalled asking Siddal to sit for him, but receiving a “freezing” refusal.

The love story between Siddal and Rossetti is like that of a tortured adolescent film script: for 10 years they were ‘engaged’, but Rossetti refused to set a wedding date. Neither was easy to live with: Siddal was addicted to the drug laudanum, and Rossetti was serially unfaithful.

Siddal learnt how to paint, and her artwork Clerk Saunders (1857) was acquired by an influential collector (Credit: Alamy)

In 1854, Siddal’s career as an artist began. Rossetti was teaching her, and when Ruskin saw her work he proclaimed her a “genius”. Her paintings were often derided by art critics, yet Siddal had only just begun learning, whereas the men of her circle had been honing their craft, under expert tutelage, for many years. Her surprisingly quick progress shows why Ruskin took such an interest in her. He gave her an annual salary of GBP150 to enable her to paint. In her full-time job at the hat shop, she had earned GBP24 a year.

In 1857, she was the sole female exhibitor at the Pre-Raphaelite Exhibition in London, where one of her paintings, Clerk Saunders (1857), was bought by an influential US collector, Charles Eliot Norton. Shortly afterwards, Siddal, whose health and relationship had been worsening for some time, gave up her annuity from Ruskin. Rossetti and Ruskin had been controlling her life and she wanted to escape. Using her savings, she took one of her sisters to the spa town of Matlock in Derbyshire. Then, instead of returning to London, she travelled to Sheffield, her father’s birthplace, to stay with her cousins. Siddal soon moved into a lodging house, and enrolled at the Sheffield School of Art, determined to make it as an artist on her own.

Ophelia by John Everett Millais (1851-2) is one of the Pre-Raphaelite movement’s most famous paintings – the model was Siddal (Credit: Private collection)

Rossetti made occasional journeys to visit her, but letters from friends in London revealed his affairs with other women, and their relationship ended in the middle of 1858. Much of what happened in her life during the next couple of years remains a mystery. Then, in the spring of 1860, she became dangerously ill. Her family contacted Ruskin and he told Rossetti, who rushed to be with her. Siddal had moved to the Sussex town of Hastings, a popular place for recuperating invalids. Rossetti arrived with a marriage licence and, as soon as she was well enough, they were married.

The beginning of the end

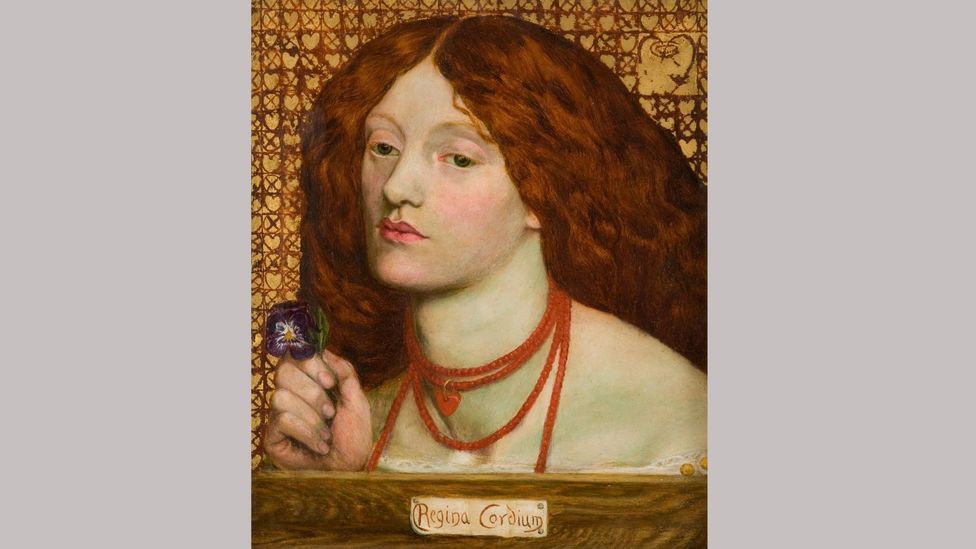

They took an elongated honeymoon in Paris, from which they returned with a pair of former street dogs they had adopted as their pets. Lizzie realised she was pregnant, and Rossetti contentedly painted and drew her, including the wistful Regina Cordium (1860). She was delighted at the prospect of motherhood, but tragically she was addicted to laudanum. Perhaps this was why, on 2 May 1861, she gave birth to a stillborn daughter.

Siddal also posed for the artist William Holman Hunt – for his painting Valentine Rescuing Sylvia from Proteus (1851) (Credit: Alamy)

She never recovered from the depression that engulfed her following her baby’s death. Their marriage suffered, and she became convinced Rossetti was, once again, being unfaithful – although his friends claimed he was faithful to her during their marriage.

On the evening of 10 February 1862, the Rossettis went out to dinner with the poet Algernon Charles Swinburne. After they returned home, Rossetti went to teach a night class at the Working Men’s College. Before he left, he saw Lizzie settled into bed – she had taken her usual dose of laudanum and there was about half a bottle left. When he returned from work, the bottle was empty. Lizzie was in a sleep so deep he was unable to wake her – and she had written him a note. Yelling for their landlady to fetch a doctor, Rossetti hid the incriminating letter.

Despite the efforts of four doctors, Lizzie Rossetti died in the early hours of 11 February 1862. On the advice of their friend, Ford Madox Brown, Rossetti burnt her suicide note. This was to ensure she was not declared a suicide and so denied a Christian burial. At the time of her death, Lizzie was pregnant again. Perhaps she feared her baby had stopped moving and could not bear to go through a second stillbirth.

Lizzie’s story does not end with her death. Due to a macabre postscript to her life, she has become a gothic cult figure. Rossetti placed into his wife’s coffin the only copy of the poems he had written. Seven years later, he decided he wanted them back.

In great secrecy, on an autumn night in 1869, her coffin was exhumed from its resting place in London’s Highgate Cemetery. Rossetti, who was by now considered ‘insane’ by some of his acquaintances, was not present. The whole operation was masterminded by his friend and self-appointed agent, Charles Augustus Howell, a flamboyant teller of tales. There were no lights in the graveyard, so a large fire was built.

Regina Cordium (Queen of Hearts) was painted by Rossetti in 1860, with Lizzie, who was by then the artist’s wife, as the model (Credit: Alamy)

Howell afterwards told Rossetti that, when the coffin was opened, his wife’s body was beautifully preserved. She was not a skeleton, he mendaciously claimed, but as beautiful as she had been in life, and her hair had grown to fill the coffin with a brilliant copper glow which shone in the firelight. Indebted to Howell’s gloriously conceived fiction is the myth of the prevailing beauty of the original supermodel, even in death – and it is a myth that ensures that, to this day, many people from around the world strangely believe that Lizzie remains undead.

A less fanciful tribute to Lizzie Siddal was written several decades later, by a former fellow student at the Sheffield School of Art. She wrote to a local paper, identifying herself only as ‘AS’: “It was a slight acquaintance I had with her, but it made a lasting impression on my memory.”

Lizzie Siddal died at the age of 32, but her extraordinary legacy continues. Her husband’s reclaimed poetry was published, to great acclaim – although the story of his poems’ provenance was kept a carefully guarded secret.

Lucinda Hawksley is the author of Lizzie Siddal, The Tragedy of a Pre-Raphaelite Supermodel, published by Andre Deutsch. Find out more via @lucindahawksley

Pre-Raphaelite Sisters is at the National Portrait Gallery in London until 26 January.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.