El Topo was the original ‘midnight movie’, and inspired the sub-genre of the ‘acid western’, writes Larushka Ivan-Zadeh.

N

New York, 1971. It’s somewhere around 1am and John Lennon is sitting with Yoko Ono at The Elgin Theatre on 8th Avenue, about to watch El Topo for the third time. The cinema is packed; lines snake around the block. The original ‘midnight movie’ has been selling out seven days a week for months, thanks to devotees rewatching it an average of 11 times. One girl has seen it 21 times. It’s the trippiest ticket in town.

A thick cloud of marijuana smoke obscures the screen, on which Lennon watches, or rather, experiences, some of the most bizarre images yet committed to celluloid. A horseman in black, a naked little boy clinging to his back, rides across a desert to ritualistically bury a teddy bear. A man with no arms carries a man with no legs towards nirvana. A mystic stands encircled by dead white rabbits. A grizzled cowboy ecstatically sniffs a pink high-heeled shoe.

More like this:

– The most outrageous film ever made?

– The classic that’s saved lives

– The film that exposed our misogynistic culture

“I wanted to do an image that a person will never forget in his life,” El Topo’s director Alejandro Jodorowsky later explained. “To create mental change. To reach a state of enlightenment. This is LSD without LSD.”

Jodorowsky worked as a clown before studying mime in Paris, joining the troupe of Marcel Marceau (Credit: Alamy)

The movie, to use the parlance of the era, blew John Lennon’s mind, as it would those of other revolutionary visionaries to follow for decades, from Bob Dylan and David Lynch to Erykah Badu, Roger Waters, the Mars Volta, Nicolas Winding Refn and Kanye West (of whom more later). “I was so lucky, because Yoko Ono was a conceptual artist and they were very interested in intellectual and spiritual things,” Jodorowsky recalled, when I interviewed him for the 2007 DVD release of El Topo. “John Lennon told his manager [Allen Klein] to give me $1million to do whatever I would like to create next.” Lennon also persuaded Klein, then head of Apple Records, to buy up the distribution rights to El Topo.

Rise and fall

Lennon’s patronage, or rather, Klein’s enforcement of it, was to make and break Jodorowsky’s career. The Chilean auteur used the $1million to make The Holy Mountain, his 1973 psychedelic masterpiece that was at one point going to star George Harrison, until Harrison balked at a request to bare his anus to the camera whilst frolicking in a fountain with a live hippopotamus. But when Klein demanded that he next adapt The Story Of O, the notorious French BDSM novella, and Jodorowsky refused, reportedly on grounds of ‘sexism’, Klein took revenge. He withdrew all of Jodorowsky’s existing films from release for over three decades – thus, ironically, stoking demand for them as fans enshrined them as cult underground classics.

In the 1960s, Jodorowsky became a disciple of a Zen Buddhist monk in Mexico City (Credit: Alamy)

Thence onwards Jodorowsky, now a sprightly 91-year-old (he insists he’ll live to see 120), became far more famous for the films of his you couldn’t see. Following The Holy Mountain, he was next approached to direct Dune, an adaptation of Frank Herbert’s 1965 sci-fi novel, and managed to spend the entire production budget before the film (which he conceived as at least 14 hours long) even started shooting. Casting Salvador Dali as a galactic emperor at the rate of $1000 per minute didn’t help – an entire documentary, Jodorowsky’s Dune (2013), was made about it.

El Topo, by comparison, remains Jodorowsky’s most accessible work. Deliberately so. His debut feature, Fando Y Lis (1968), was a kinky, post-apocalyptic romance between the mysterious Fando and his paraplegic girlfriend, Lis. It incited riots on release in 1968, was banned in Mexico and was shown for just three days in South America. Hurt, its director declared: “The next picture I make will be a cowboy picture – then everyone will come and see it.” El Topo was that movie.

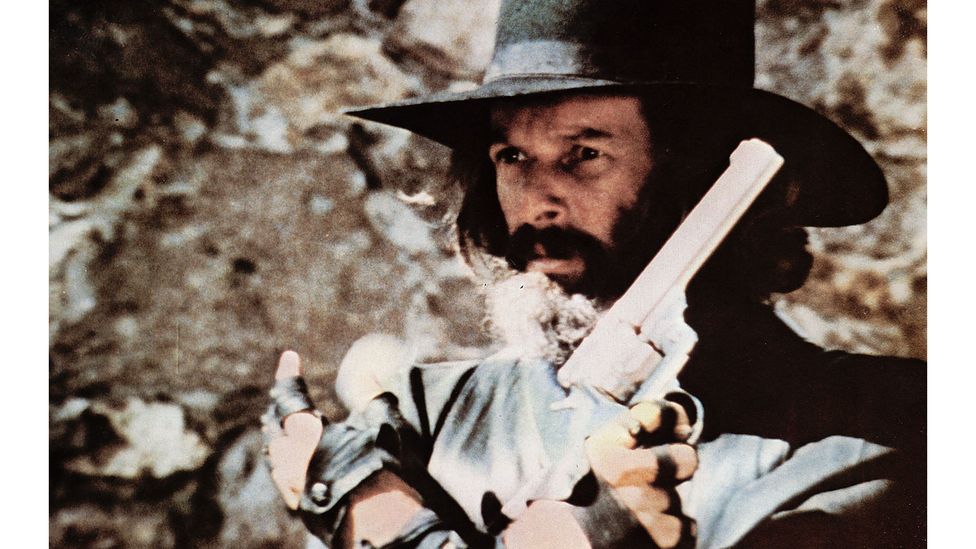

After his debut feature was banned in Mexico, Jodorowsky vowed to make a ‘cowboy picture’ (Credit: Alamy)

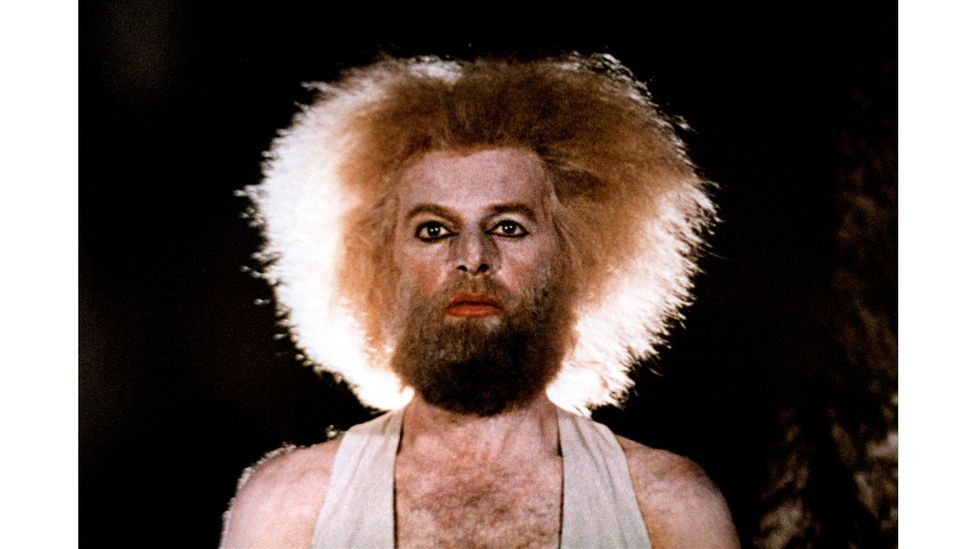

A bloody spaghetti western, heavily infused with Eastern spiritualism, it centres on a hero (played by Jodorowsky himself), who is the Western genre’s archetypal ‘man in black’. Known only as ‘El Topo’ (‘the mole’), he is an enigmatic, leather-clad gunslinger who travels the plains with his naked seven-year-old-son (Jodorowsky’s own son, Brontis). In the opening section, father and son encounter a grisly massacre. They track down the evil ‘Colonel’ behind it and castrate him, rescuing Mara, a beautiful young woman (Mara Lorenzio) who is being threatened by the Colonel’s henchmen. ‘El Topo’ then abruptly abandons his son to fulfill a mission set by Mara. He defeats a series of ‘gun masters’, only to be shot, seemingly dead, by another incredibly beautiful woman. The film’s second half sees him wake up, pale with a ginger shock-haired wig, looking rather like a Fraggle in a nappy. He is in a cave inhabited by a community of disabled people, who venerate him as a savior before he sets himself alight and undergoes transmogrification by bees.

Creating a whole new sub-genre, the so-called ‘acid western’, El Topo is a heady, arguably at times unwatchable, brew of Chinese philosophy, Zen Buddhism, astrology, Sufism, European surrealism, the Kabbalah and, above all, the tarot, a life-long passion for Jodorowsky, who has written many a treatise on the subject and created his own deck. In this overwhelming melange of baffling allegory, it’s fair to say that story or plot is not a priority, and, as with the intuitive meanings of tarot, you have to tune in or drop out.

That it became a cult hit in 1971 New York was a question of right time, right place. It’s not hard to see its appeal to Lennon and other leading lights of the contemporary counter-culture, who were looking to the East for new mind-expanding philosophies. Though even the most esoteric head freaks at the time struggled to keep pace with Jodorowsky, who concluded one hilarious 1971 interview by insisting that “a piece of cheese can be Christ” to a bewildered ‘uh huh’ by the journalist.

In El Topo, a wandering Mexican bandit goes on a search for spiritual enlightenment (Credit: Alamy)

So mischievous a showman is Jodorowsky, you can’t help but wonder how much of his far-out craziness is an act. When I interviewed him in 2007, the twinkly-eyed auteur had a bodyguard present “in case you attack me!”. He insisted that this was a real threat during the tarot readings he regularly conducts. To disarm him, I said that El Topo has often been praised as ‘the greatest film ever made’, and would he agree? He beamed. “I am so happy when they say that! My ego – she grows. I must be careful, or I will explode one day. I have no idea why they would say this, unless it is because my liver is the best liver in creation.” Your liver? “Yes. My work comes not from critical thoughts, but from out of myself. I made El Topo out of total artistic honesty. I didn’t want money, I didn’t want to work with big stars. I wanted nothing, except to do my art.” So what is the goal of art? “To show others how beautiful is their soul. The beauty of the other. To open up consciousness.”

Jodorowsky’s own uncompromising artistic odyssey began when he left Chile for Paris in the 1950s to study mime under Marcel Marceau. Here his short, mime-based films soon caught the eye of Jean Cocteau. Shifting between Paris and Mexico City, he became involved in the ‘Panic’ movement, a chaotic experimental theatre group set up in 1962 out of a belief that modern surrealism was becoming too accessible. They created more than 100 plays, or ‘happenings’, such as Sacramental Melodrama, a four hour-long melodrama that reportedly involved Jodorowsky slitting the throats of two geese and taping snakes to his chest, some naked women covered in honey, a crucified chicken, a giant vagina and a can of apricots. I guess you had to be there.

But the artistic and the spiritual were always entwined. A showman also venerated as a shaman – he officiated at Marilyn Manson’s wedding to Dita Von Teese in 2005 – Jodorowsky has spent decades developing his own unique brand of therapy called ‘psychomagic’. Its core belief is that that the performance of key traumatic moments can heal one’s psychological wounds. His own films play out like dark Freudian melodramas. Literally born from trauma, after his abusive father raped his mother, Jodorowsky sprang to life, unwanted and unloved, in the Chilean coastal town of Tocopilla in 1929. Growing up, he was mocked for being a Jewish immigrant – his parents originated from what is now known as Ukraine.

Jodorowsky has plans to make a sequel called The Son of El Topo (Credit: Alamy)

Aged 23, Jodorowsky disowned his parents, but couldn’t disown the complexes they created. El Topo is the first in an autobiographical trilogy including The Dance of Reality (2013) and Endless Poetry (2016), which cast his eldest son Brontis variously as his own father, grandfather and himself. A process that proved traumatic in itself for the young boy. At the opening of the film, El Topo tells his son: “You are seven years old. You are a man. Bury your first toy and your mother’s picture.” The act proved so upsetting to Brontis that afterwards Jodorowsky had to let the child dig his teddy up, telling him “now you can be a child”. He later expressed guilt over this that he didn’t feel at the time.

“A person is not the same in his life at all times,” he told Vulture in 2014. “Your consciousness is developing all the time. When I started making El Topo, I was one person. When I finished that picture, I was another person. And when I made El Topo, I was just asking [Brontis] to kill some rabbits. ‘Just!’ Because at the time, I said to myself, ‘we should give everything to art’. So when I finished the picture, I became more human, and asked forgiveness from my child. I’d never kill an animal; I became conscious. If you don’t make errors, how can you be conscious?”

In 1962, Jodorowsky founded the Panic Movement along with Fernando Arrabal and Roland Topor; its members embraced absurdism (Credit: Alamy)

The exploitation of children, the differently abled and a relentless cruelty towards animals – ironic given Jodorowsky is a lifelong vegetarian – are what date his film films today. That and the unreconstructed misogyny. El Topo features a rape scene between El Topo (played by Jodorowsky) and Mara, which in 1972 Jodorowsky said had happened for real. Comments he reneged on in 2019 as just “surrealist publicity” that he now “regrets”.

Such highly problematic elements aside, El Topo and the rest of Jodorowsky’s unique, opaque, yet dazzlingly original universe remains weirdly timeless. Unlike anything you’ll see before or since, it exists within its own cult bubble, both man and work continuing to influence artists a full 50 years later.

Around five years ago, for example, Jodorowsky was asked to meet with Kanye West. “It was very surrealistic,” he told an audience at the British Library in 2015, “because I knew nothing about Kanye West. They said he is a rapper and he thinks you are a genius. You inspired him to make a show about Jesus.” Initially the meeting was awkward, since Jodorowsky had no idea why he was there. To break the ice, Jodorowsky offered to read West’s tarot. The rapper picked ‘The Fool’ to represent himself and ‘The World’ representing his destiny. “This Kanye West is a man of enormous ambition. He is searching for meaning. Maybe for this he came to me. I said you have the sun in your hands, that maybe means you can do whatever you want. It was a very, very amazing and beautiful tarot and he was very touched. He picked me up and then threw himself on the floor and then continued as if nothing happened. He was a like a child. Very sympathetic. Immediately I liked him.”

The detail that most impressed Jodorowsky, however, was that West and his entourage only drank water. For, incredibly, all Alejandro’s own psychedelic visions are created without chemical assistance. “I never take drugs,” he has said, “because I have these experiences without.” That’s surely the most mind-blowing thing of all.

Love film and TV? Join BBC Culture Film and TV Club on Facebook, a community for cinephiles all over the world.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.