Thirty-five years ago, Larry Kramer’s play The Normal Heart told of another US epidemic, the Aids crisis – and denounced the indifference to it. Jack King reflects on its power.

I

In July 1981, 26 cases of Kaposi’s sarcoma, an exceedingly rare cancer, were identified exclusively in gay men by doctors in New York and California. This came some weeks after a report was published by the Centre for Disease Control and Prevention describing how five previously healthy gay men had been diagnosed with pneumocystis pneumonia. These were opportunistic infections resultant of Aids, a chronic condition caused by the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) which effectively destroys the immune system. HIV had been spreading, undetected, through America’s gay population since around the early 1970s, a result of sexual transmission among a demographic whose promiscuity was not only a convention of queer sociability but a revolutionary political act in the wake of the 1969 Stonewall rebellion.

Ninety-five and a half per cent of those diagnosed with AIDS between 1981 and 1987 died. As Dr Paul Volberding, a San Francisco medic who helped to set up America’s first hospital inpatient ward for Aids sufferers, recalled to The Guardian in 2016: “This is the most fatal infectious disease ever seen. Without treatment, 98% die. More than Ebola. More than Smallpox.”

More like this:

– The film that showed a US in chaos

– A civil rights anthem of ‘plaintive optimism’

– The Great American painting?

It was not until 24 September, 1982 that the CDC would use the acronym Aids; medical practitioners had up to that point designated the novel virus Grid (Gay Related Immune Deficiency), or more colloquially ‘gay cancer’, or ‘gay plague’ — the implication being that this was an exclusively gay disease. Conventional logic should tell us that viruses do not discriminate, but in a US lurching towards social conservatism under the Reagan administration, this was perfect ammunition for right-wing pressure groups such as Jerry Falwell’s Reagan-allied Moral Majority. Falwell proclaimed Aids to be the “the wrath of God,” a view that spread into public opinion; comparing the crisis to the Holocaust in 1988, the playwright William H Hoffman wrote: “as with the present situation, the general population by and large viewed the victims with a mixture of fear, hatred and indifference.”

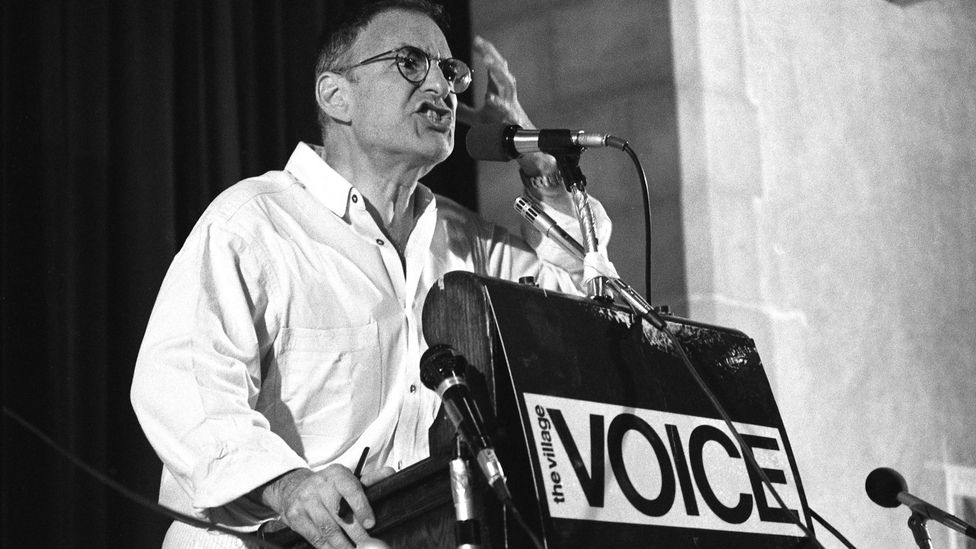

The Normal Heart writer Larry Kramer was driven to activism by the Aids crisis, and helped to set up the US’s first Aids support clinic (Credit: Getty Images)

In the face of such prejudice, one artwork fired back above all others: Larry Kramer’s The Normal Heart. The play, which premiered off-Broadway in May 1985, viscerally chronicles the earliest struggles faced by the Gay Men’s Health Crisis, the first Aids support clinic in the US, co-founded by Kramer in New York in 1982. Having begun his career as a Hollywood screenwriter before moving into writing for the stage, Kramer, who died in May aged 84, had never conceived of himself as a gay activist – in fact his 1978 novel, Faggots, a scathing critique of the then norms of queer promiscuity, had made him persona non grata in New York’s gay community in the early 1980s. But the world needed a call-to-action, Kramer believed – and he could provide it.

A portrait of a warzone

In his foreword for a 2000 collection of two of Kramer’s plays, The Normal Heart and 1992’s The Destiny of Me, the Angels in America playwright Tony Kushner writes: “Here are two plays that, taken together, offer a persuasive account of a critical, terrible era when an emergent community, laboring to set itself free from centuries of persecution and oppression, was blindsided just at the moment of a political and cultural attainment of some of its most important goals by a biological horror miserably allied to the world’s murderous indifference, its masked and its naked hatred.”

It’s powerful commentary from the writer of what is largely considered to be the other pinnacle of the now canonised literary works of the Aids crisis – for to read Kushner’s analysis is to understand, fully enough, not only the legacy of The Normal Heart but its searing intent. It was politics-as-art born in the scalding hot embers of a brewing crisis that would go on to claim the lives of 700,000 Americans, predominantly of queer and black communities, and has, to date, killed 33 million people globally. Kramer wrote The Normal Heart to “catalyse his society”, as Kushner continues, “which we all know theatre can’t do anymore, except on the rare occasions when it does, as when Larry Kramer wrote The Normal Heart.”

The roman-a-clef recalls the first years of the North American Aids crisis from the perspectives of a rag tag group of gay activists, together forming the Gay Men’s Health Crisis against a backdrop of political inaction; the play’s protagonist, Ned Weeks, is a thinly veiled analogue for Kramer himself. It is an unforgiving, prosaic text, largely free of metaphors or poetry, building in righteous anger as the years pass and more men die to a disease that Ned and his comrades see as ignored not only by those of political influence but by society at large. Kramer’s portrait of what a generation of gay men suffered renders America akin to a warzone, where the corpses of victims are refused death certificates and left to collect dust in oversized refuse bags, and funerals become so frequent as to be social events.

“I read the play a year before it was first staged,” Craig Lucas, the writer of another seminal Aids drama, Norman Rene’s 1989 film Longtime Companion, tells BBC Culture. “It had been making the rounds of not-for-profit theatres and everyone was saying it was agitprop and not really a play.” Lucas’ partner Tim was training as Chief Resident at New York Hospital in 1984, witnessing a significant upsurge in Aids cases, when he too began showing symptoms. “We were both out of our minds with anxiety and dread and certainty that we would die soon. Larry’s amazing, passionate struggle to be heard blazes in the play; at the time it felt shockingly alive and important and it hit me and a lot of other people like a tsunami,” Lucas continues. “Politically, the play could not be more important.”

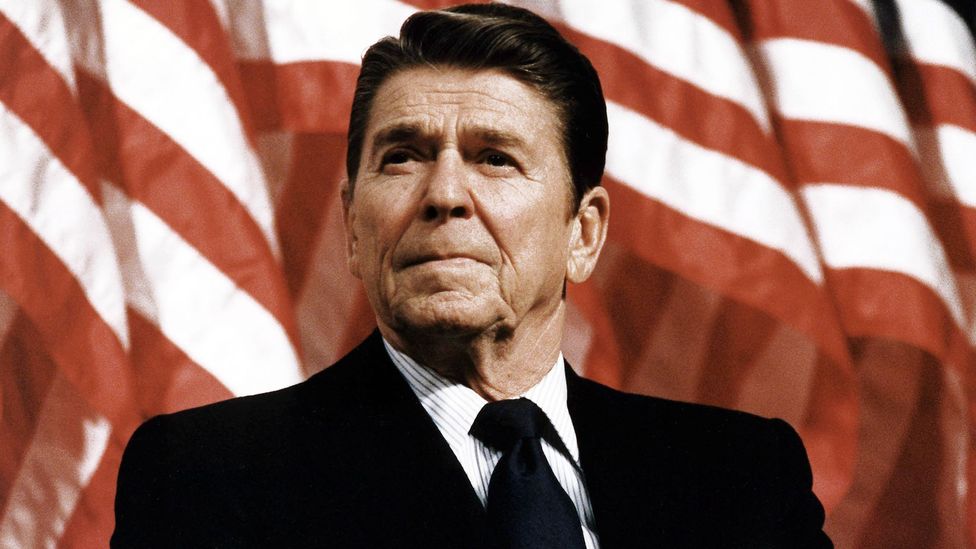

Critics of Ronald Reagan believe he was tainted by his ‘halting and ineffective’ reaction to the Aids crisis, in the words of biographer Lou Cannon (Credit: Alamy)

Ronald Reagan’s personal attitude towards the Aids crisis continues to be a matter of discussion: many then and now believe his presidency was tainted by his “halting and ineffective” reaction to it, to use the words of prominent biographer Lou Cannon. This is not so dissimilar, of course, to the way critics of the Trump administration are currently attacking what they consider to be his trundling response to the Covid-19 pandemic. The central difference is that Aids was perceived to be a gay-only disease long into the 1980s by an unsympathetic public, so there was little-to-no pressure on Reagan to respond, his political capital unthreatened by his silence.

At the same time, the notion that he himself was a homophobe is disputed: some argue that he was privately sympathetic to those living with Aids, regardless of his administration’s policies. That he was surrounded by bigots, however, is a matter of historical record: Pat Buchanan, who served as the White House Communications Director from February 1985 to March 1987, described the crisis as nature “exacting an awful retribution against gay men” in a 1983 op-ed for the New York Post; the White House Press Secretary Larry Speakes, described as “the public face of the Reagan Era“, repeatedly sparred in briefings with journalist Lester Kinsolving on questions of Aids, oft with the pejorative implication that the latter was gay. Reagan himself would not publicly acknowledge the epidemic until 17 September 1985, six months after The Normal Heart had premiered. By the end of the year, 12,529 Americans had died, including Reagan’s close friend Rock Hudson.

The art of the Aids crisis

If we are to understand the Aids crisis to be one of the defining events of Reagan’s presidency, then The Normal Heart must be considered one of the definitive polemics of Reagan’s America. Reagan’s administration itself seldom draws the direct ire of Kramer, so much as the policy of apathy that Kramer viewed as having become structurally de rigueur under his presidency, from the media to the New York mayor’s office to the public; The New York Times, for example, is a frequent villain. “Have you been following this Tylenol scare?” Ned asks one colleague, Bruce, in reference to a real-world swathe of Tylenol poisonings occurring in 1982, which left seven people dead. “The Times has written fifty-four articles. […] For us – in 17 months they’ve written seven puny inside articles. And we have a thousand cases!” It is a portrait of a crisis not taken seriously by those who perceive themselves not to be under threat, indifferent to a besieged other.

It did not, of course, manifest in an artistic vacuum: 1985 also brought the first feature films to focus explicitly on the Aids crisis, Artie Bressan Jr’s Buddies and the made-for-television An Early Frost, and William M Hoffman’s play As Is opened in New York’s Lyceum Theatre mere weeks after The Normal Heart was first staged. Subsequent years brought the New Queer Cinema movement, with films including Rene’s aforementioned Longtime Companion, Bill Sherwood’s Parting Glances (1986), and Todd Haynes’ allegorical Aids anthology, Poison (1991); and the activist works of artists such as David Wojnarowicz, Keith Haring and Robert Mapplethorpe. All of these men, aside from Kramer, Hoffman and Haynes, would die due to complications resulting from Aids.

Whilst much of the art that stemmed from the crisis was equally as affective, no single other work quite possesses Kramer’s level of vigour. It’s a play structurally akin to sustained mortar fire, bombarding its audience again and again with incredulous rage at what he deems a deathly negligent polis. Its unparalleled power stems in part from the fact everything within the play is so hot off the press; Kramer had none of the time for reflection that, say, Kushner had with Angels in America, which premiered in 1991, 10 years after the epidemic is officially recorded to have begun. The Normal Heart is a primal howl from the frontline, with all of its mud and viscera, expressive of the fact that when your friends are dying all around you, you have no choice but to act urgently.

The Normal Heart found a new audience when it was made into a television film starring Mark Ruffalo in 2014 (Credit: Alamy)

Discussing the play with BBC Culture, the playwright Matthew Lopez, best known for his recent two-part queer epic The Inheritance, recalls the first time he read the play, in drama school. “I remember it feeling so hot on the page – it was blistering. It felt like the text was on fire. You could feel the energy emanating from it. I first saw it at the Public Theater at a revival in 2004, which confirmed for me what I’d always believed about it. It was, and remains, the essential text of the epidemic.”

In one scene, Ned’s brother, Ben, a lawyer for a major New York law firm, refuses to sit on the board of the GMHC, which Ned takes as not only a tacit denouncement of the organisation’s attempts to save gay lives but of his own queerness. “You make me sound like I’m the enemy,” Ben argues. “I’m beginning to think that you and your straight world are our enemy,” Ned exclaims. “I’m trying to understand why nobody wants to hear we’re dying, why nobody wants to help – why my own brother doesn’t want to help!” It is an explosion of despair, anguish, exhaustion, fear and turmoil; he speaks, no doubt, for many of those affected by Aids in the early years of the crisis, the parents suddenly without sons, and lovers suddenly without partners.

The legacy of The Normal Heart, Lopez contends, is not “just as theatre, but of history; it’s living history, as rarely contemporaneous as you ever get” – while, 35 years on, it also acts as a vital reminder of the continuing battle not only against viruses, but also political neglect, he suggests. “I think we’re evolutionarily conditioned to have a kind of amnesia about things,” Lopez continues. “And it seems as though the impulse is to soften memory; memory starts to soften focus over time. What the great value of that play is, it will forever remind us of exactly what the crisis was.” It’s a text, Lopez believes, that is key to understanding Reagan’s political legacy – a subject on which he does not mince words. “I think the Aids crisis was a genocide of neglect. It was the central story of his presidency, nothing else.” Reagan’s defenders can point to the fact that, when he did come to speak out about Aids, he asserted it was one of his administration’s highest priorities on more than one occasion – while by the final year of his presidency in 1989, the federal government was putting $2.3 billion into HIV/Aids research and prevention. But others would claim this was still too little, too late.

“The Normal Heart is our history,” writes Kramer in his epigraph for the play’s script. “It could not have been written had not so many of us needlessly died. Learn from it and carry on the fight. Let them know that we are a very special people. An exceptional people. And that our day will come.” It may seem that that day has arrived for those living in the West, where gay people are by and large afforded unprecedented legislative rights and privileges, the great project of assimilation having largely succeeded. However the popular memory seems to erase the fact that Aids continues to claim the lives of 13,000 Americans every year, disproportionately gay men of colour in the US South. What is certain is that The Normal Heart remains as incandescent as it was in 1985. It is thunderous, bellowing, and to read its fiery prose is to feel Kramer’s fury at what he perceived as wanton callousness – and to reflect on how that fury may continue to resonate.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.