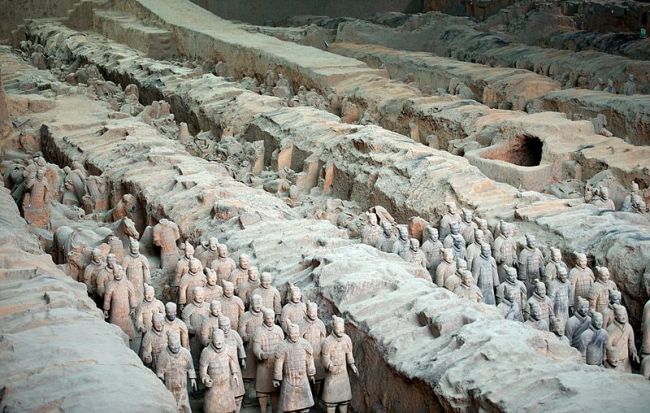

In a tomb near a hallowed mountain in Northwest China, legions of warriors stand guard for eternity. Facing to the east, and arrayed with military precision, these grim soldiers have stood their ground for over two millennia, guarding the resting place of China’s first emperor, Qin Shi Huang.

This life-size honor guard is known today as the Terracotta Army, for the mixture of fired clay that shapes each figure. Discovered in 1974 by farmers digging in a field, the army is one of the most well-known wonders of China today, right after the Great Wall.

A warrior on display. (Credit: Zhao jiankang/Shutterstock)

The spectacle of an eternal fighting force is captivating, but the Terracotta Army is also fascinating for what it represents. Thousands of laborers toiled to build the necropolis in which the warriors stand, and an entire economy of craftspeople and workshops was involved in the creation of the thousands of figures that make up the army.

The resulting masterpiece is a picture-perfect image of an ancient Chinese fighting force, armed and ready for battle. Perhaps nowhere else are we granted this kind of glimpse into history: a testament to the wealth and power of the first Chinese empire, built for the very man who created it.

An Army of Clay

The Terracotta Army is thought to contain around 7,000 soldiers, in addition to statues of entertainers, officials and more. They look to the east, toward the conquered territories of the Qin empire, perhaps to fend off would-be invaders after the emperor’s passing. The

army, created in the third century B.C., was equipped with real weapons made of bronze, in addition to chariots and hundreds of terracotta horses. Some 40,000 arrowheads have been recovered from the tomb, as well as bronze swords, spears, battle axes, crossbows, shields and more.

The weapons were found in an astonishing state of preservation which led some researchers to speculate that craftspeople in ancient China had discovered a special metallic coating to preserve their implements for the ages. Those speculations were based on traces of the element chromium, also present in stainless steel, found on the bronze weapons. But more recent research put that theory to rest. The chromium likely came from the lacquer coating the statues, scientists now think, and the weapons were instead preserved by the unique alkaline soil.

The figures vary in both size and dress. Officers are both taller and more lavishly equipped than the regular infantry, decked out with kits of armor and decorative sigils of rank. Faces differ from soldier to soldier, lending the warriors another touch of realism. The soldiers were originally decorated with a rich palette of colors including white, red, green, blue and black, though their paint has since faded.

The Terracotta Army is thought to contain around 7000 soldiers. (Credit: kevinmcgill/Wikimedia Commons)

The inanimate warriors are part of a much larger necropolis complex that spans more than 20 square miles. Along with his army, Qin Shi Huang’s tomb contains bronze carriages, terracotta musicians and artificial rivers replete with bronze birds. The rivers were said to have once flowed with liquid mercury, an assertion backed up by elevated mercury levels in the soil nearby. The emperor’s tomb itself, marked by a large earthen mound, has never been opened for fear that the contents might be damaged by exposure to the air.

The warriors were found in a collection of pits located to the east of the main burial complex. The largest pit contains an estimated 6,000 soldiers (some have yet to be excavated) arranged into precise groupings containing infantry, archers, charioteers and crossbowmen, overseen by officers. A second pit has a smaller force of cavalry and other

soldiers, while a third contains a command unit of 68 high-ranking officers.

When archaeologists first began uncovering the terracotta warriors, it was clear that some catastrophe had befallen them long ago. Many of the figures were smashed, and there were signs of a fire in the tomb. The destruction is usually attributed to Xiang Yu, a warlord vying for the throne after Qin Shi Huang’s death. He and his men are said to have looted the emperor’s tomb, including the weapons within, and leaving it to burn. Consequently, the warriors were found shattered in the dirt, awaiting painstaking reconstruction by archaeologists.

Building the Terracotta Warriors

The emperor’s tomb, and the figures that fill it, were built over the course of more than three decades between 246 and 210 B.C., when Qin Shi Huang died. Some historical estimates put the number of workers involved at around 700,000, though more contemporary estimates indicate the process could have involved far fewer. Historical records also note that the emperor created an entire city, Liyi, to house the workers building his tomb, some of whom never left. A cemetery near the site contains the remains of workers who died either during the grueling work of construction or who were killed shortly afterward.

The process of creating the Terracotta Army itself would have involved a great deal of organization and industrial precision, as well. Workers were likely organized into so-called cells that were responsible for a number of different steps in the process, as opposed to an assembly line-like production arrangement. Though no evidence of workshops has been found near the tomb, it seems improbable that the warriors were made far away, given the logistical difficulties of transporting more than 7,000 heavy, breakable figures over long distances.

An illustration of Qin Shi Huang by an unknown artist, circa 1850. (Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

The clay itself was blended with care, likely by a specialized team of laborers. Analyses of samples from the tomb indicate that different formulations of clay were used for different purposes: Sand was added to the clay used for the warriors, for example, and may have been used to control how sticky it was. Once shaped, the warriors were fired in a kiln to

harden them.

The warriors were made by using a number of standardized molds for heads, torsos, limbs and more, then assembling these components later before adding facial features and lacquer. Similarly, the weapons seem to have been mass-produced in specialized shops. All of the lances and halberds, for example, are inscribed with the year they were made, the

name of the official in charge of production, the workshop and the specific worker that made it.

The work of creating thousands of life-size figures and installing them on the grounds of a massive necropolis spanned decades. Many workers died to bring this inanimate army to life, and the emperor funneled large sums from his vast treasuries into the project. But,

given what we know about Qin Shi Huang, the first Chinese emperor, the project makes sense.

The subject of impending death exerted a powerful pull on the emperor — he is rumored to have died as the result of drinking a supposed elixir of life that turned out to contain poisonous mercury. With death at hand, perhaps he drew comfort from the thought of his

own immortal army waiting for him.