Two new novels lift the lid on the odd, privileged world of the British Royal Family. Hephzibah Anderson talks to their authors.

W

We first encounter royalty through fiction. Shimmering princesses and blessed princes, monarchs both wise and wicked – they all inhabit the formative fairy tales that teach us so much about life, weaving their narrative magic as densely as the briar thicket that envelops Sleeping Beauty. The institution’s motifs, its crowns and its thrones, the heavy sense of predestination spelled out in curses and golden promises, are stitched into our collective imaginations before we’re old enough to know it. In adulthood, we mostly come to realise that the charmed, ‘fairy tale’ element of life as a royal is decidedly double-edged: yes, the red carpets are rolled out for them but their celebrity is inescapable from birth, and the dazzle of gemstones is accompanied by the blinding glare of flashbulbs. So often, palaces double as gilded cages.

More like this:

– The best books of the year so far

– How royal women have shaped fashion

– Is it time to re-write fairy tales?

And yet it’s a hard fascination to shake, not least because the members of this intriguingly anachronistic-seeming institution remind us of a time when our own passion for make-believe, long ago snuffed out by the unbending minutiae of grown-up life, was insatiable. But as two new novels show, fiction can still teach us plenty about royalty, giving authors access to private moments and inner selves from which biographers and historians are barred by protocol and red tape. And just like those nursery fables, royal fiction retains its power to educate.

As children, many of us first encounter royalty through fairy tales, such as The Sleeping Beauty (Credit: Getty Images)

Given the ubiquitous role that royals play in childhood, it’s ironic that theirs have traditionally turned out to be so dysfunctional. This is what two new novels, The Governess and A Most English Princess, excel at revealing. Their authors, bestselling Wendy Holden and first-timer Clare McHugh, both grew up fascinated by royalty. In Holden’s case, she would pore over the sepia photographs in a book belonging to her grandmother, commemorating the coronation of George VI, father of Britain’s current Queen Elizabeth II. “While I thought the crowns and furs were amazingly glamorous, it was the characters that drew me,” she recalls. “They all seemed like characters from fiction to me and from that point on, albeit subconsciously, I wanted to put them in a novel. But it wasn’t until I found the amazing story of Marion Crawford that I found the right way in.”

Marion Crawford was a career girl with a social conscience who’d planned on teaching in the slums of Edinburgh. Instead, she ended up becoming governess to two princesses, Elizabeth – known as Lilibet – and her little sister Margaret. She was with them for 17 years until her retirement in 1948, whereupon she made the fatal error of writing a book about her experiences with the Windsors. The publication of The Little Princesses saw her frozen out of royal life forever.

Its revelations are tame by modern standards, Holden says. Not that its pages didn’t contain surprises of the kind that set a novelist’s mind whirring. “It provided an unexpected and touching glimpse of our ultra-composed Queen as a worried child, a vulnerable human being.”

Until ‘Crawfie’, as she became known, breezed into their lives, the sisters weren’t allowed to get their clothes dirty, and had to stick to the paths out in the garden. “She brought her woke ideas with her, and took them out into the world to show them normal life. She took them on the Tube, shopping at Woolworth’s and even swimming at public baths,” Holden says. While other girls her age were dreaming longingly of the trappings of royalty, enchantment for young Lilibet was her first glimpse of a London Underground escalator. “The stairs are moving!” Holden has her exclaim in cut-glass tones, showing how an excessively sheltered upbringing becomes a kind of disadvantage.

‘Crawfie’ was governess to the Princesses Elizabeth and Margaret, and showed them aspects of ordinary life (Credit: Getty images)

“Royal upbringings can be very damaging if they make royalty seem remote from the people, who hate arrogance and entitled behaviour,” Holden says. “Crawfie felt that Lilibet and Margaret were living a formal, sequestered, Victorian life which had no place in the modern world. She thought this wasn’t good for them either personally, as people, or practically, as members of the ruling family. And so she took them out of the palace and showed them how ordinary folk lived. She encouraged their humour, their creativity and their sense of adventure, all of which were being utterly suppressed when she arrived.”

Thanks in no small part to Crawfie, a woman whose name Holden says is still synonymous with betrayal in royal circles, that worried, vulnerable child was able to weather some of the most seismic years in her nation’s history. “Crawfie steered them through the abdication, the unexpected coronation of their parents, and the whole of World War Two. While this was all very dramatic and brilliant to fictionalise, it must have been very frightening and confusing at the time.”

Holden’s novels have sold more than three million copies globally but The Governess is her first foray into historical fiction. Though she immersed herself in the period, raiding her nearest second-hand bookseller for out-of-print books collected by local monarchists, her own imagination, she says, was her most important source of all. Allowing herself the freedom to invent was what McHugh, who has behind her a 30-year career in journalism, found hardest. Her novel, A Most English Princess, dramatises the life and turbulent times of Queen Victoria’s eldest child, the Princess Royal known as Vicky, a pawn in international politics who was married off to a German prince and gave birth to the future Kaiser, Wilhelm II, who in turn plunged his nation into World War One.

Leap of empathy

“I fretted over authenticity,” says McHugh, who lives in Connecticut but was born in London, and whose British great-grandfather once drove Vicky’s son and brother, King Edward VII, on part of their journey to Osborne House, the Royals’ Isle of Wight residence. “How could I ever imagine, accurately, what it was like to be a princess, and then a German Empress, and then a bereft widow, living in a huge castle, despised by one’s son?”

Queen Victoria’s daughter Vicky, seen here in a 1863 portrait, is the subject of a new novel by Clare McHugh (Credit: Alamy)

“Get in her head and stay there,” was the advice given to her by novelist Sandra Newman. The letters Vicky wrote home to her mother helped immensely but McHugh also spotted parallels that made Vicky’s story seem altogether more relatable. “The Royal Family first and foremost is a family,” she says. “All the kinds of things that happen in families happen to them, in terms of the rivalries and invidious comparisons that were made, but all the stakes are higher.”

It’s a salient point, especially taking into account another key difference: while the rest of us may make lives for ourselves outside our family of origin, royal persons are defined first and foremost by their lineage. It’s almost impossible for them to achieve anything that supersedes the luck (or otherwise) of their birth. And birth order and gender are everything. As McHugh notes, from the very start, Vicky occupied a peculiar position in her family. Not only was she the eldest, she was also the brightest and the most capable of the royal couple’s nine children.

A dauntless and optimistic child, she attended science lectures, read books like Uncle Tom’s Cabin, and was schooled by her father in government and history. Yet the rules of succession meant she had no chance of inheriting the throne. All the same, she was too valuable to be allowed to forge her own path. At just 17, she left one gilded cage for another that was infinitely more restrictive, when she was married off to the future Frederick III, German Emperor and King of Prussia, as part of her father’s scheme to bring modern democracy to Germany. McHugh portrays a genuine, deeply physical attraction between the newlyweds, but it’s still a political match, and one that takes her far from home.

There’s a scene in the novel that epitomises every princess fantasy. Vicky, a girl who knows she is no beauty, attends a French ball wearing a dress designed for her by Empress Eugenie herself – a lavish garment with half a dozen tiers of white lace flounces, trimmed with peach velvet and posies of fabric flowers. Entering the Palace of Versailles is like “entering a vast, jewel-encrusted treasure chest”. And yet, she was damaged by her privilege, McHugh believes, raised to be entirely confident in her own opinion but heedless of what anybody else had to say, partly because her status meant that nobody ever told her the truth. Meanwhile, her father’s praise made her mother, whom he was in the habit of scolding, jealous.

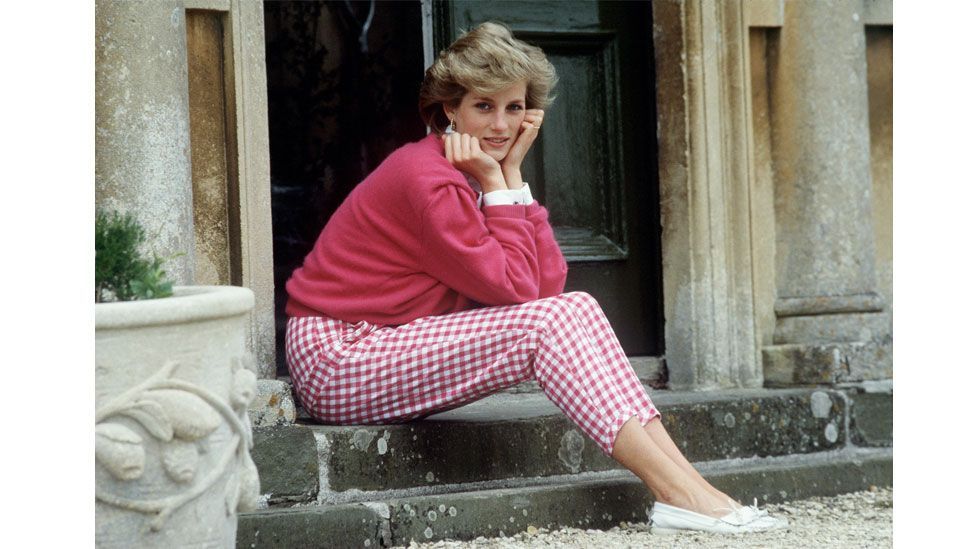

Her position has even counted against her posthumously. “She is underrated by history, and dismissed as an unsuccessful and rather pathetic royal figure. Then and now prominent people, royal or otherwise, are subject too often to hostile interpretation – in Vicky’s case it reached a crescendo with Freud analysing her faults from beyond the grave,” McHugh explains. “My take is that Vicky was a luminous personality who tried her best in a strange, nasty, misogynistic world.” It was this insight that helped McHugh make the final leap of empathy that fiction requires in order to come alive. It also gives her novel a contemporary thrust. From the late Princess Diana to the Duchesses of Cambridge and Sussex, royal women in this century and the last have still had to deal with plenty of misogynistic judgement. “We live in a different world, and a much better world, but I hope there are echoes of these efforts of women to try to be positive forces in political and familial roles,” she says.

The late Princess Diana is among the many women who have experienced a difficult time as a royal (Credit: Getty Images)

Much as their position rests upon tradition, royal families do evolve. Marion Crawford may have been iced out of the Queen’s life, but let’s not forget that she was employed with the Royal Family for almost two decades, plenty long enough to become what Holden insists is a fundamental influence on her long reign, and on the way she raised her own children. “These days when people talk about the Queen’s good sense and common touch, qualities that have bolstered her authority throughout her reign, I always think of Crawfie and how that started with her,” Holden says. All the same, as in any epic narrative, patterns repeat themselves. Just consider how events are playing out for the Duchess of Sussex, who recently entered the house of Windsor only to end up back on the outside.

As McHugh points out, the royals epitomise privilege and entitlement, but they are also human beings trapped in very odd and distorting circumstances. “It isn’t a deal I would take,” she says. “I think there’s a debate to be had about whether or not the cost to the royal family is too high. Let’s remember, they’re being used.” Strangely, despite the liberty-taking that is so essential to a fiction-writer’s craft, it’s when real royals become literary characters that this strange life becomes most honest, and most enlightening.

The Governess (or The Royal Governess in the US) by Wendy Holden is out now, and A Most English Princess by Clare McHugh is published on 22 September.

Love books? Join BBC Culture Book Club on Facebook, a community for literature fanatics all over the world.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.