A searing new novel by the mysterious author is as unflinching as her millions of fans have come to expect. Clare Thorp explores the extraordinary phenomenon of ‘Ferrante fever’.

T

There is a moment right at the start of Elena Ferrante’s new novel The Lying Life of Adults where the narrator seems uncertain if her experience is one worthy of telling. She describes herself as “only a tangled knot”, not yet sure if that knot contains “the right thread for a story or is merely a snarled confusion of suffering, without redemption”.

More like this:

– Surprising secrets of writers’ first drafts

– The myth and reality of the Parisienne

– The greatest summer novels ever written

Stories – which ones get told, which don’t, who gets to tell them, and which ones we value – are a recurrent theme in Ferrante’s writing, and this new one has an eager audience. Published on 1 September in English, it is the Italian writer’s first book in five years, and the first since the enormous success of My Brilliant Friend and her Neapolitan quartet of novels sparked ‘Ferrante Fever’, and turned the author – who writes under a pseudonym – into one of the most well-known writers in the world.

Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan quartet has been adapted into a critically acclaimed HBO TV series (Credit: Alamy)

When The Lying Life of Adults was published in Italy late last year, people queued from midnight to get their hands on a copy, and ‘reading vigils’ were held across the country. A Netflix adaption is already in the works. The English translation, already pushed back several months because of the pandemic, can’t come soon enough for Ferrante fans.

That her new book opens with a question mark over what makes a compelling narrative is fitting. Ferrante herself has defied expectations of what stories writers – specifically women – get to tell, and in doing so, has shifted the literary landscape both in her native Italy and around the world. “Reading Ferrante is a completely immersive intellectual and emotional experience,” says Sharlene Teo, whose debut novel Ponti drew comparisons with Ferrante when it came out in 2018. “I’m a massive fan and I’d never try and imitate her, but I look up to her work massively. She’s singular because her writing is both compulsively readable and incredibly textured and full of literary beauty, depth and rhythm.”

Ferrante was a familiar name in her native Italy long before she found worldwide success. Her first novel, L’amore molesto, came out in 1992 (translated into English as Troubling Love in 2006). Her next, The Days of Abandonment, came ten years later. By then her Italian publisher was sure there was a wider audience for her writing, and tried to find a US publisher for the book. When no-one was interested, they set up their own publishing house, Europa Editions, in 2005 to publish Ferrante and other international literature in the UK and US.

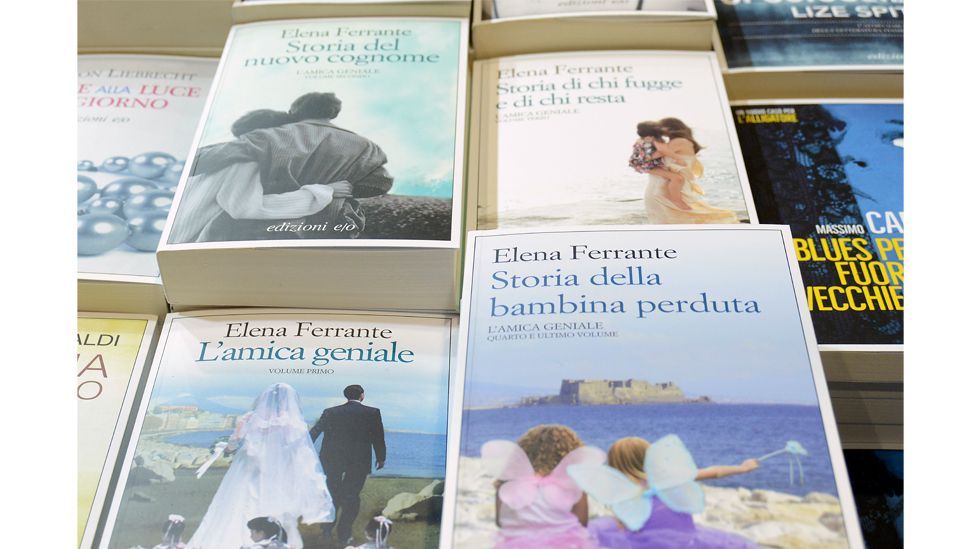

The Neapolitan novels by Ferrante have sold 15 million copies worldwide, in 45 languages (Credit: Getty Images)

In 2012 – a year after it had been released in Italy – Europa published the English language edition of My Brilliant Friend, the first of her Neapolitan quartet. Eva Ferri is publishing director of both Europa Editions UK and Edizioni E/O, Ferrante’s Italian publishing house, founded by Eva’s parents Sandro and Sandra in 1979. Ferri knew My Brilliant Friend was something special when her father first read it and – being unusually effusive for him – declared it “an absolute masterpiece”.

Originally conceived as one book, until Ferrante realised the story was too expansive for a single volume, the Neapolitan novels follow two friends, Elena and Lila, from their childhood in an underprivileged neighbourhood in Naples and throughout six decades. A glowing review by The New Yorker’s James Wood in 2013 described Ferrante’s books as “intensely, violently personal novels”, and helped put her on the radar of more readers.

By the time the final book in the series, The Story of the Lost Child, was published in 2015, Ferrante fever had truly taken hold. Copies were passed to friends, while people obsessed over them on social media. Hillary Clinton said she “could not stop reading or thinking about” the books.

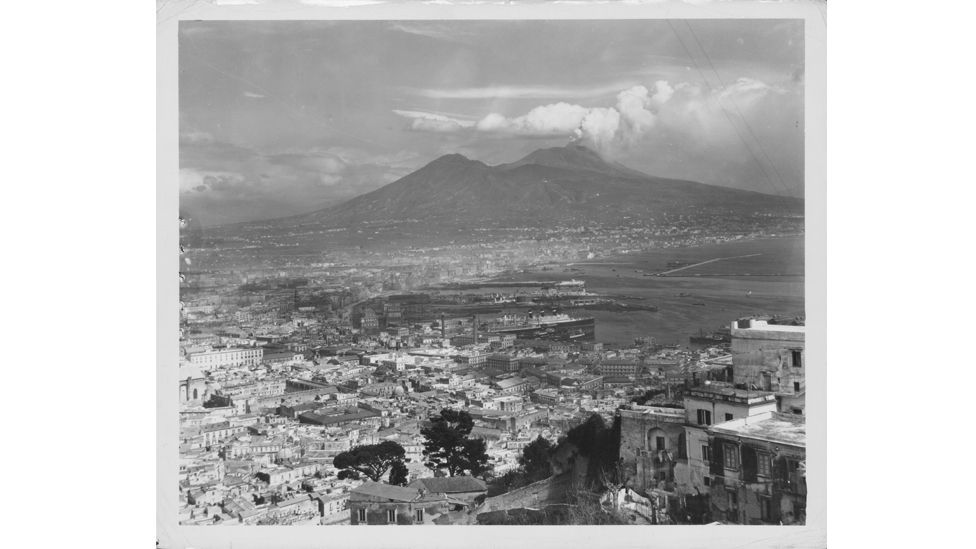

Naples in the mid-20th Century is the setting for much of Ferrante’s work (Credit: Getty Images)

For some, the author’s decision to remain anonymous added extra allure – though when a journalist claimed to have unmasked her in 2016, fans angrily defended her right to privacy. In a letter to her publisher when she was first signed, Ferrante explained her decision, saying: “I believe that books, once they are written, have no need of their authors. If they have something to say, they will soon find readers; if not, they won’t.”

They certainly found them. To date, the Neapolitan novels have sold 15 million copies worldwide, are published in 45 languages, and have been adapted into a critically-acclaimed TV series (the second season aired earlier this year). There’s even a booming Ferrante tourism industry in Naples.

As impressive as all this is, her impact goes deeper. “Here is a writer who is telling the truth,” says Jonathan Franzen in the 2019 documentary, Ferrante Fever – and Ferrante’s truth is more unflinching than most. Whether writing about female friendships, adolescence, sex, motherhood, marriage or class, she is breathtakingly bold in both the detail and the honesty with which she tackles her subjects.

“Her writing is completely uncompromising, which is something that has been helped, I think, by the fact that she protects her identity,” Ferri tells BBC Culture. As one of the few people with a direct line to the author, Ferri is not just her publisher but also her protector (as a teenager attending parties and book fairs with her parents, Ferri would be offered drinks by people in a bid to extract information about the author from her). “She feels free and she is free to speak in a way that is completely direct.”

Hearts and minds

It is not uncommon to hear Ferrante fans say that the writer has somehow got inside their head – that they recognise in her words parts of themselves they have never seen expressed on the page before. Maggie Gyllenhaal, who is adapting Ferrante’s third book, The Lost Daughter, into a film starring Olivia Colman and Dakota Johnson, said of her reaction when reading the book: “I have never heard these things articulated before. There was one point where I was like, ‘This woman is so fucked up’, and then I was like, I totally relate to her.”

Ferrante tells her stories with unflinching, uncompromising honesty (Credit: Alamy)

In a piece she wrote for the New York Times last year, Ferrante talked of the importance of women telling their own stories. “We women have been pushed to the margins, towards subservience, even when it comes to our literary work,” she wrote. “The female story, told with increasing skill, increasingly widespread and unapologetic, is what must now assume power.”

Besides inspiring devotion among fans, her commitment to writing as an act of truth-telling strikes a chord with a new generation of novelists. “The worlds she’s summoned in fiction constantly inspire me to try and be more courageous, interrogative and assertive of my subject position as a diasporic female Singaporean writer,” Teo tells BBC Culture.

Teo – who admires how “almost painfully, viscerally affecting” Ferrante’s work is – believes the writer’s success has also revealed a thirst for literature that explores the “knotty ambiguities and self-reflection” in friendships, especially between women. “There’s definitely been an uptick of female-friendship narratives that have emerged over the past six or seven years, I think spearheaded by Ferrante,” she says.

Elena and Lila are the central characters of Ferrante’s quartet – season two of the TV series came out earlier this year (Credit: Alamy)

In her home country of Italy, Ferrante’s success hasn’t always been celebrated by the literary establishment, where commercial success – especially by women – can be viewed with suspicion. Fellow Italian writer Nadia Terranova – whose upcoming fourth novel Farewell, Ghosts will be her first published in English (she shares Ferrante’s translator, Ann Goldstein) – was not surprised. “In Italy, there were many great female writers in the last century, but they did not have the same [critical] recognition as their male colleagues, even when they were really popular. On the contrary, their popularity was used to despise them,” she says.

Stories of the female experience have often been sidelined – with Ferrante’s achievements dismissed as ‘soap opera’ by some Italian critics, and the Neapolitan quartet receiving a few tepid reviews. “This literary magnificence was acknowledged just in part, maybe because we always expect a man to write a great novel,” says Terranova.

The past few years have seen a shift, though. The percentage of books by female writers on the Italy’s fiction bestseller lists has doubled to nearly half the total number in the past two years. In 2018, a woman – Helena Janeczek – won the country’s prestigious Strega prize for the first time in 15 years (Ferrante has been nominated but has never won). Terranova says Ferrante has opened a door for other female writers in Italy. “There are many different and original female voices in Italy – we never lacked courage, and now we have more eyes on us.”

Ferrante’s new novel further explores themes of adolescence and friendship – and the lies we tell to others and to ourselves (Credit: Europa Editions)

In her new book, The Lying Life of Adults, Ferrante touches on familiar themes – adolescence; mother-daughter relationships; sexuality; intense yet fractious friendships. Unlike the sprawling Neapolitan saga, its focus is narrower, following a girl, Giovanna, from the age of 12 up until 16, as she encounters an adult world marked by deception. The book begins with Giovanna overhearing a conversation between her parents in which, she believes, her father describes her as ugly, comparing her to his estranged sister, Vittoria. Once again, the city of Naples looms large as a character. Whereas My Brilliant Friend began with two girls in an impoverished neighbourhood dreaming of escape, Giovanna lives high up in the city – literally and metaphorically – with her academic parents. As she strives to discover the truth behind her parents’ lies, she descends into “the depths of the depths of Naples”.

Ferrante explores the lies we tell, to others and ourselves. Giovanna searches for truths, but is herself seduced by the power of a lie. There are few better than Ferrante at capturing the confusions and contradictions of the space between childhood and adulthood, where one identity disappears and another is still out of reach. Giovanna is searching for herself, her story. Like all Ferrante’s works, it’s not a neat story, not a pretty one – but it’s one that needs to be told.

Love books? Join BBC Culture Book Club on Facebook, a community for literature fanatics all over the world.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.