For many people, the story of the Aztec crystal skulls begins and ends with the least memorable Indiana Jones movie in the storied franchise. To others, the crystal skulls have mystical psychic and healing powers. However, despite the Hollywood theatrics and online hype, not a single crystal skull has ever been pulled from an excavation site. The crystal skulls are all archaeological imposters.

And yet the real story of these fake crystal skulls is nonetheless filled with intrigue and mystery.

Are the Crystal Skulls Real?

In major museum collections around the world, you can find masterfully carved and haunting crystal skulls in all manner of styles and sizes. The smallest is a simple amulet, while the largest is bigger than a bowling ball. And for generations, museum visitors have been captivated by their allure. Even today, you can still see some on display.

But in the 1990s, an anthropologist named Jane Walsh at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History started to develop suspicions about these objects.

One day, the U.S. Postal Service delivered a football helmet-sized Aztec crystal skull to the Smithsonian Institution from an anonymous donor. The note claimed it formerly belonged to a Mexican dictator. A colleague gave the skull to Walsh to look after. She knew about the skulls’ history as popular museum attractions. And Walsh was also aware of their dubious side, having exhibited a skull in a museum exhibit that labeled it a fake. As she examined the new arrival, she spotted a handful of reasons to doubt it was a genuine artifact.

“It was much too big, the proportions were off, the teeth and circular depressions at the temples did not look right, and overall it seemed too rounded and polished,” Walsh and a colleague, Brett Topping, wrote in their book, The Man Who Invented Aztec Crystal Skulls: The Adventures of Eugene Boban.

And as she eventually started digging into the backstories of other crystal skulls, she saw a trend of clear red flags and a strange pattern of similarities.

Soon, modern scientific analyses would also show that these crystal skulls were cut with modern rotary tools, while in some cases, the rock originated from Brazil, rather than Mexico.

Science of the Crystal Skulls

Walsh started by examining the origins of a 2-inch crystal skull in a Smithsonian Institution collection. It had appeared seemingly out of nowhere in the late 1800s as part of a collection that came to the museum from Mexico. And in a catalog card written in the 1950s, she found an analysis done by a geologist named William Foshag — an expert in Mesoamerican carved stones.

Foshag’s investigation revealed that the object was “definitely a fake,” created with modern jewelry-making tools and techniques. In a trove of documents that accompanied the larger collection of artifacts, she also stumbled onto a potential suspect involved: a man named Eugene Boban. An 1886 letter claimed that this man had tried to sell a fake crystal skull to Mexico’s national museum.

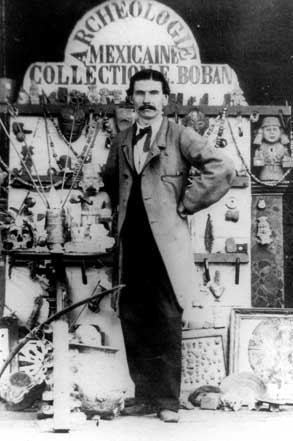

Eugene Boban, a French antiquarian based in Mexico. (Public Domain/Wikimedia Commons)

Boban’s name would eventually appear throughout the investigation. One tiny crystal skull owned by the British Museum traced its origins through the prestigious Tiffany & Co. of New York. Records showed that a company partner bought it at a Boban auction in 1897. Again and again, their detective work seemed to trace the story of the crystal skulls back to a specific time frame — from the 1860s to the 1890s — and a single man, Boban. But who was he?

Boban and Fake Mexican Artifacts

Boban, a Frenchman born in 1834, was enthralled by Mexico and its history. He traveled there extensively and over the years, he eventually became an archaeologist working for a member of the French Scientific Commission in Mexico. Boban developed friendships with many of the greatest archaeologists of his day, and took great interest in collecting artifacts from across the region. Through catalogs and exhibitions, he sold artifacts to collectors and museums in the late 19th century.

Around the same time, experts had started noticing fake Aztec and pre-Columbian artifacts flooding museum collections. An 1886 article in the journal Science decried “the trade in spurious Mexican antiquities.”

The museums themselves weren’t ignorant about fakes, but they also didn’t know enough to avoid them. So, increasingly, they started turning to subject experts for help. That’s how Boban got his start. As Boban built a reputation as an expert in Mexican antiquities, museum curators trusted him to arrange deals. They couldn’t have realized that he was selling them forgeries — or that he had invented crystal skulls — because they didn’t know Aztec society well enough. Boban banked on that. And he managed to hide the skulls’ origins through fake purchase histories.

Who actually made the skulls then? In many cases, Walsh suspects Boban may have acquired them from aging Christian churches in Mexico that the government was tearing down. We may never know. But Boban himself also seemed to tip off future generations to his complicity in the crystal skull saga when he talked to a newspaper journalist in the year 1900.

Boban said: “Numbers of so-called rock crystal, pre-Columbian skulls have been so adroitly made as almost to defy detection, and have been palmed off as genuine upon the experts of some of the principal museums of Europe.”

Tower of Skulls

Meanwhile, real archaeological artifacts were also streaming out of Mexico. Excavations were uncovering new clues about the Aztec, a civilization that was just as advanced as its contemporaries in Europe. And museums and private collectors around the world were eager to get a piece of it. Curators were snatching up objects that seemed rare and exotic. Crystal skulls would have seemed like the perfect get.

Centuries ago, Aztec spiritual beliefs and ceremonies placed major significance on the human skull. They carved ornate skulls into stone and depicted their gods wearing human skulls as jewelry. When the Aztecs sacrificed humans, they’d rip out people’s hearts and put their heads on stakes.

In fact, between 2015 and 2017, archaeologists dug up a monumental Aztec tower at Templo Mayor in Mexico City that’s some 20 feet in diameter and was built from more than 650 human skulls. The discovery of this skull tower belies the staggering scale of human sacrifice happening in what was then the Aztec capital city. It also shows just how obsessed their culture was with the skull.

It wasn’t just the Aztecs, either. Going further back into history, the Maya and the Olmecs before them also used skulls in their spiritual practices and their art.

Mesoamerican people were also known for carving ornate sculptures and ceremonial objects out of hard stone and gems, including crystal. One of the most beautiful examples of their craftsmanship is a pair of goblets carved from crystal.

Open Questions

When you combine the pre-Columbian fascination with skulls with the technical prowess at carving stone, it may have been easy for some to believe that these ancient people could have carved skulls out of crystal. And for nearly 150 years, that subtext helped a number of museum exhibit curators feel comfortable about displaying their crystal skulls, despite long-standing questions about these objects’ true origins.

It was only thanks to a number of investigations like Walsh’s in recent years that archaeologists have largely come to the consensus that these crystal skulls are fakes. Some still display them from time to time because of the public’s extreme interest.

That doesn’t mean that all museums necessarily agree though.

On the British Museum’s web page detailing the crystal skull that came through Tiffany & Co., the curator’s notes include a wide range of hypotheses on where the object originally came from and how it was made, including notes about modern tools. But it stops short of calling it a fake.

“Other speculations as to the origins and possible use of the crystal skull are legion,” the site reads. “The question remains open.”