The long history of racism in war movies

As Netflix releases Spike Lee’s film Da 5 Bloods, about African-American Vietnam veterans, it’s a reminder of how profoundly Hollywood has whitewashed conflict, writes Kaleem Aftab.

D

Director Spike Lee’s new film, Da 5 Bloods, is a Vietnam war film with a difference. It tells the story of four African-American veterans, played by Delroy Lindo, Clarke Peters, Isiah Whitlock Jr and Norm Lewis, who reunite after decades apart and return to Vietnam to find the body of their former colleague (Chadwick Boseman) and locate a hoard of gold bars that were being used by the US to pay their South Vietnamese allies. As they do so, Lee shows how they all carry trauma specific to them as black soldiers from the failure to appreciate their war effort, on top of the ongoing prejudices targeting all black Americans.

Warning: This article contains strong language that might cause offence.

More like this

– A masterpiece about US racism

– Hollywood’s most problematic stereotype

– The film that changed how we see sport

In the flashback scenes, meanwhile, Lee shows how the US’s history of systemic racial prejudice and abuse was exploited by the Vietcong, who dropped leaflets about American civil rights crimes and the assassination of leading black figures such as Martin Luther King, Jr in order to try and persuade black soldiers to stop fighting.

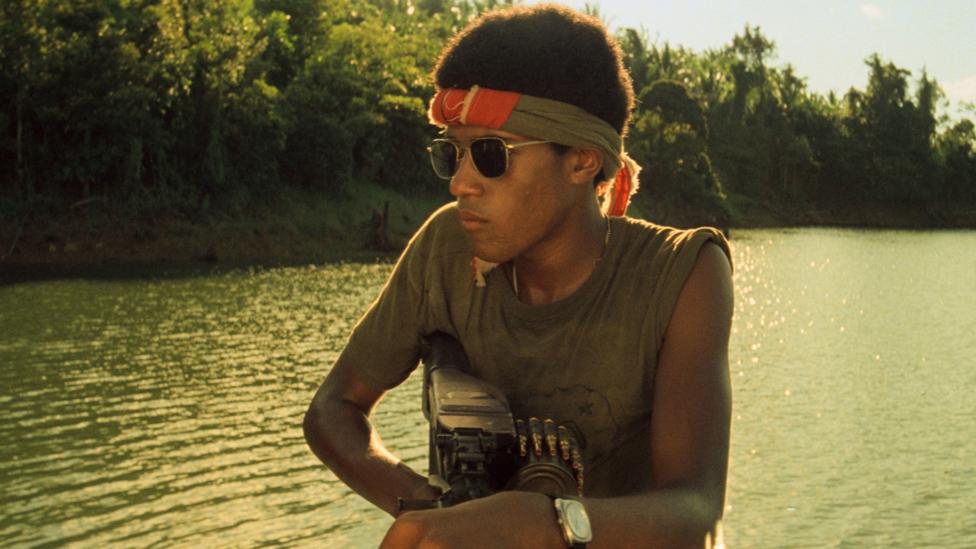

Da 5 Bloods focuses on four African-American veterans who return to Vietnam to find the body of their former colleague – and a hoard of gold (Credit: Netflix)

When Lee first received the script for Da 5 Bloods, it was about four white veterans, and had once been destined to be filmed by Oliver Stone. Working with his regular co-scriptwriter Kevin Wilmott Jr, Lee then made these characters African-American and recontextualised the whole story. In looking at war through an explicitly racial prism, it feels revelatory.

Powerfully, it all begins with archive footage of the legendary boxer Muhammad Ali talking on camera in 1978 about why he refused to fight in Vietnam: “[The Vietnamese] didn’t put no dogs on me, they didn’t rob me of my nationality,” he said.

Over a decade earlier, Ali had been sentenced to five years in jail for draft dodging; his heavyweight title and boxing licence were revoked, though he stayed out of prison while he appealed against the decision. Then, in 1971, the Supreme Court finally sided with the boxer, declaring that he was a bona-fide conscientious objector and not an illegal draft dodger.

War on two fronts

Ali’s words come at the beginning of a montage featuring stills of African-Americans fighting in Vietnam, Neil Armstrong landing on the moon, Malcom X delivering a heartfelt speech, Tommie Smith and John Carlos raising a fisted glove on the medals podium at the Mexico ’68 Olympics, images of poverty in Harlem, and civil rights activist Kwame Ture (Stokely Carmichael) arguing “America has declared war on black people”. Then comes perhaps the most potent soundbite – philosopher Angela Davis arguing “if the link is not made between what is happening in Vietnam and what is happening here, we may very well face a period of full-blown fascism soon.”

Originally, Lee created the sequence because, in framing his tale of the Vietnam war, he wanted to remind people of the wider context of what was happening at home in the late 1960s and 1970s. “There was a war in Vietnam, but there was a war in America too.” At the time, Ali was one of those who helped emphasise that what was going on in Vietnam had these parallels at home, aligning the civil rights battle with that of the communist Vietcong fighting against imperial oppressors – and suggesting how the enemy of African-Americans was the same as the enemy of the North Vietnamese.

But the film’s emphasis on the parallel conflict on the home front now feels horribly timely, landing at a moment when protestors have taken to the streets around the world demanding an end to US state brutality following a police officer being charged with the murder of George Floyd. Some would say that the US seen in the montage seems no different from today. Indeed, the day before I spoke to Lee about Da 5 Bloods, he put up a short film, 3 Brothers, on his Instagram account. The film mixes real footage of the deaths of Eric Garner in New York City in 2014 and George Floyd in Minneapolis last month, with the scene from his landmark 1989 masterwork Do the Right Thing of the character Radio Raheem dying after being put in a police chokehold (itself inspired by the death of graffiti artist Michael Stewart in 1983.)

Dunkirk (2017) is a recent example of a war film that whitewashed history (Credit: Alamy)

“Maybe, it was the plan of the highest, highest,” says Lee about Da 5 Bloods being released at this time of agony. “I try not to spend too much time thinking about why things happen. You just have to accept things that you have no control over, and I know that this thing is bigger than me. But I am happy that this film is coming out now, because a lot of the stuff in the film is speaking directly about a lot of the stuff that is happening.”

In the flashback scenes to the war, Lee uses the same actors but doesn’t age them down, a la Martin Scorsese’s The Irishman, a decision that reinforces the idea that our history is part of our present. We are our past – as individuals and nations. It’s also in keeping with Lee’s Brechtian filmmaking style, which breaks the fourth wall, and is at pains to remind us that the story has social relevance to our present.

How black soldiers were marginalised

It’s a damning insight on the US movie industry, that more than 40 years after America pulled troops out, Da 5 Bloods can lay claim to be the first film centring the experience of African-American Vietnam soldiers. For decades, they have been kept on the periphery of films depicting the conflict, even though in 1967, the demographic represented 23 percent of all combat troops in Vietnam, and in 1965, a quarter of all US combat deaths.

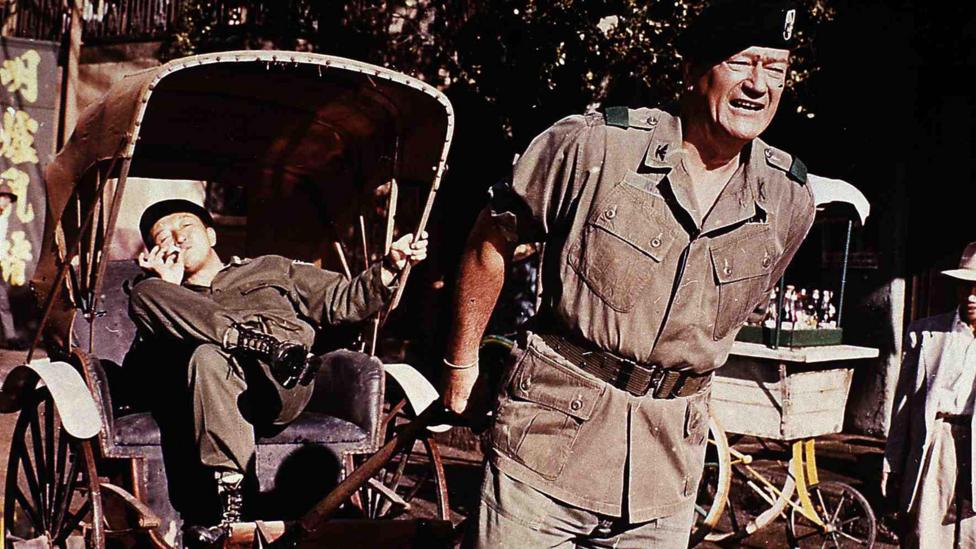

Watch films from John Wayne’s The Green Berets (1968) onwards and you’ll find the African-American experience is rarely reflected, while the treatment of the Vietcong and even the South Vietnamese allies is arguably even worse. Typically, the story of Vietnam is told from the perspective of a white American soldier, and theirs is the only experience made to count.

It should be pointed out that this whitewashing of war is not just the preserve of ‘Nam movies. Lee states that the first germ of his desire to reframe the ‘Nam movie came from watching black and white World War Two films as a child. “Growing up in Brooklyn, my late brother Chris and I used to watch [them] on television. And we liked them. But my father would see us and tell us that black folks fought in World War Two.”

Cinematic history is almost exclusively made up of war films that celebrate the white hero. You only have to look at the big war films of the last few years to get a glimpse into the enduring problem. Take Christopher Nolan’s Dunkirk, for example: in 2017, the writer and academic Sunny Singh wrote an article about the film titled ‘Why the lack of Indian and African faces in Dunkirk matters‘, in which she described it as a “fantasy disguised-as-historical war film”. Singh decried Nolan’s complete erasure of the Royal Indian Army Services Corp companies, which were tasked with transporting supplies; the lascars – mostly from South Asia and East Africa – who counted for one of four crewmen on British merchant vessels; and the north African troops in the French army. It’s important, Singh argues, “because, more than history books and school lessons, popular culture shapes and informs our imagination not only of the past, but of our present and future”.

John Wayne’s Vietnam war film The Green Berets (1968) was produced with government aid, and was slammed as propaganda (Credit: Alamy)

The tradition of racial erasure in war movies means that even when filmmakers do the right thing, critics often suggest that the truth is a lie and claim wrongly it’s an example of diversity gone mad. The most infamous recent British example of this came when the outspoken British actor Laurence Fox criticised “the oddness in the casting” of a Sikh soldier in Sam Mendes’ World War One film 1917. Hardeep Singh, writing in The Spectator, ironically thanked Fox for his misinformed contribution: “He has done more (in the space of 48-72 hours) to highlight the inordinate contribution of Sikh soldiers during the Great War, than most Sikhs could ever wish to achieve in this life or the next.”

Lee tried to redress the balance with his 2008 adaptation of James McBride’s World War Two novel Miracle at St Anna, which focused on the 92nd all-black infantry division known as the Buffalo Soldiers. However the film was greeted by critics as one of the prolific director’s minor works, even as many acknowledged the significance of its undertaking.

A critique of Vietnam movies

Da 5 Bloods is a much more entertaining and complex film which, following on from 2018’s BlacKkKlansman, shows Lee is in the middle of a second golden period. It is a work that is clearly aware of its own position in the pantheon of Vietnam war movies – and implicitly critiques its predecessors throughout. One of the first scenes takes place in a club called Apocalypse Now, and as in the Francis Ford Coppola film of the same name, those words are seen on screen as graffiti. Lee explains that he paid homage to Coppola’s film because of its inclusion of two African-American characters: the soldiers played by Laurence Fishburne, who was 14 years old at the time, and Albert Hall.

These characters were far from central protagonists in the movie – that honour fell to Martin Sheen and Marlon Brando. But they were given defined personalities – Fishburne’s Clean loves rock ‘n’ roll, motorcycles and freedom – and the film also showed some awareness of the fact African-Americans were more likely to die in action: in the infamous Do Lung Bridge battle scene, all the soldiers fighting on the frontline are black, an implicit acknowledgement of the disproportionate number of African-American serviceman who were sent to the frontline and died in action.

Certainly, when it came to race, Coppola’s film was a step forward from the most famous ‘Nam film up that point, The Green Berets. The only film about the war to come out during the war itself, it follows Colonel Kirby (Wayne) and his Green Berets from their training camp in the United States to a Special Forces Outpost in Vietnam. It was produced with government aid, and was rightly slammed as propaganda. As well as featuring just a single token black character – Doc McGee, played by Raymond St Jacques, the dependable medic, who is praiseworthy because of his unquestioning patriotism and deference to his white colleagues – it depicted both the South Vietnamese allies, and the north Vietnamese enemy forces, in a way that completely dehumanised them and rendered them indistinguishable, offering a continuation of the ‘yellow peril’ trope, that saw Hollywood portray East Asians as homogenous adversaries to Western values.

Oliver Stone’s Platoon (1986) highlighted racial divides amongst US troops – though it was all refracted through the memories of a white veteran (Credit: Alamy)

In the mid-1980s, Oliver Stone’s Platoon followed in Apocalypse Now’s footsteps by offering a slightly more sophisticated depiction of the conflict. It portrayed racial divides amongst American troops, that were mainly defined by cultural ties: soldiers were either predominantly white ‘juicers’, who drank, or predominantly black ‘heads’, who smoked marijuana. However, while Stone highlighted issues of race and class, the representations of black soldiers we see are all refracted through the memories of a white veteran: Stone himself, who wrote the script based on his experiences as well as directing. And its depiction of the Vietnamese was still crude to say the least: indeed, from Platoon to Stanley Kubrick’s 1987 film Full Metal Jacket, it’s difficult to remember a ‘classic’ Vietnam war film with an Asian woman who is not a sex worker, or in which the Vietcong are not depicted as faceless savages.

One film that did better on this front was Barry Levinson’s Good Morning, Vietnam, loosely based on the career of real-life Armed Forces Radio Services DJ Adrian Cronauer. Released in 1987, it surprised at the time in its depiction of its Vietnamese characters with their own interior lives, as family members, friends and lovers.

Vehicles for white supremacy?

Most popular and most egregious, however, were the Reagan-era films that tried to rewrite the conflict as a victory for white supremacy, with pumped-up action heroes like Chuck Norris (Missing in Action) and Sylvester Stallone (Rambo First Blood: Part II) playing Vietnam veterans returning to the country to rescue prisoners of war and gun down their old enemies. In another post-modern nod, the characters in Da Five Bloods debate and slam these very movies (“Do you all remember those fugazi Rambo movies?” “All those Holly-weird [people] trying to go back and win the Vietnam war.”)

“If I may say so respectfully, America got their ass kicked by a very small nation, in the same way France did, so [these films] had to rewrite the narrative,” says Lee, reflecting on this sub-genre. “I guess there is a large part of Americans who couldn’t deal with reality.”

Since then, there have been few depictions of Vietnam that have had much impact on the public consciousness or revised Westerners’ understanding of the conflict (though one notable work was Randall Wallace’s We Were Soldiers (2002), which gave the North Vietnamese soldiers a human face by giving as much time to the perspective of Lt Colonel Nguyen Huu An (Don Duong) as it did to Colonel Hal Moore (Mel Gibson)). So Da 5 Bloods feels long overdue.

Reagan-era action films like Rambo First Blood Part II tried to rewrite the Vietnam conflict as a victory for white supremacy (Credit: Alamy)

Lee was conscious of redressing the problematic history of ‘Nam movies on two fronts: not just in his depiction of black soldiers, but in his portrayal – and casting – of the Vietnamese characters. A major issue with nearly all previous films about the war is how directors were happy to cast anyone from Asia as Vietnamese. But Lee made sure to use only Vietnamese actors, even though a lot of the film was shot in Thailand, so it would have been expedient and cost-effective for the director to use Thai actors, especially for background extras. “A lot of films would be like ‘fuck it, we can’t get any Vietnamese people, and just employ someone from China, Japan, no one is going to notice.’ It’s racism. I was not doing that.”

Casting aside, Vietnamese characters are also given a proper voice. The principal ones are Vinh (Johnny Tri Nguyen), a tour guide whose father fought in the war for the South, while his uncle was on the side of the Viet Cong; and the savvy businesswoman Tien (Le Y Lan), who had an affair with one of the serviceman, with whom she had a mixed-race daughter, subsequently finding herself demonised as a result. Among other Vietnamese the main quartet encounter are those ready to fight them over the gold, which they see as rightfully theirs, and those unwilling to forgive the atrocities of the war.

Our US protagonists are similarly varied. They argue over everything, including politics – one is a Trump supporter – and money. Some are absent or bad fathers, and they are all characters with massive foibles. Their lives have been defined, and broken, by the war.

Hopefully, with its global Netlix platform at a time when few other major films are being released, Da 5 Bloods will enjoy the kind of visibility that could open the door to a more diverse range of stories about war: ones that offer a truer, less archetypal reflection, of what happened on and off the battlefield. War movies have been some of the worst culprits in propagating racist, white-focused narratives. Though of course they are just a microcosm of a problem that runs through Hollywood, as Lee points out. “I think as far as Hollywood goes, for the most part the story has always been told from the white narrative, so that’s not restricted to war. It’s from top to bottom.”

Da 5 Bloods will be available on Netflix from 12 June.

Love film and TV? Join BBC Culture Film and TV Club on Facebook, a community for cinephiles all over the world.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.