Susanna Clarke’s latest novel Piranesi is set in a house with countless rooms. Cameron Laux explores why we’re drawn to impossible spaces.

W

What could the conservative Catholic Irish writer CS Lewis (1898-1963), famous for the Narnia books, and the postmodernist Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges (1899-1986), famous for short stories that play in ‘labyrinths’ of meaning, possibly have in common? Well, for one, they share a fascination with impossible spaces and magical worlds. For another, their influences converge in Susanna Clarke and her recent novel Piranesi.

More like this:

– Why the funniest books are also the most serious

– The best comic novel ever written?

– The book that changed Japan’s image

In interviews, Clarke has attempted to engage in the contradictory act of explaining the delicate obscurities and puzzles that are at the heart of her writing. “You start with an image or the fragment of a story, something that feels like it has very deep roots into the unconscious, like it is going to connect up with a lot of things,” she told The Guardian. Yet there is a sense that Clarke’s labyrinths aren’t meant to be solved, but rather dis-solve. Going to her looking for direction may be a waste of time, because even she might not understand them. Not understanding might be essential.

In 2004, Clarke’s debut novel Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell was published, a charming, dark, eccentric pastiche of Regency literature that defied expectations by going stellar and selling more than four million copies. Neil Gaiman, a god among fantasy writers, called it “unquestionably the finest English novel of the fantastic written in the last 70 years”. It was made into a TV series that preserved its wonderful strangeness. It is a book about the magical things and impossible places that could lurk behind the dull everyday, notably a cold, surreal, sinister faerieland which the careless or unfortunate or power hungry might lose their way in.

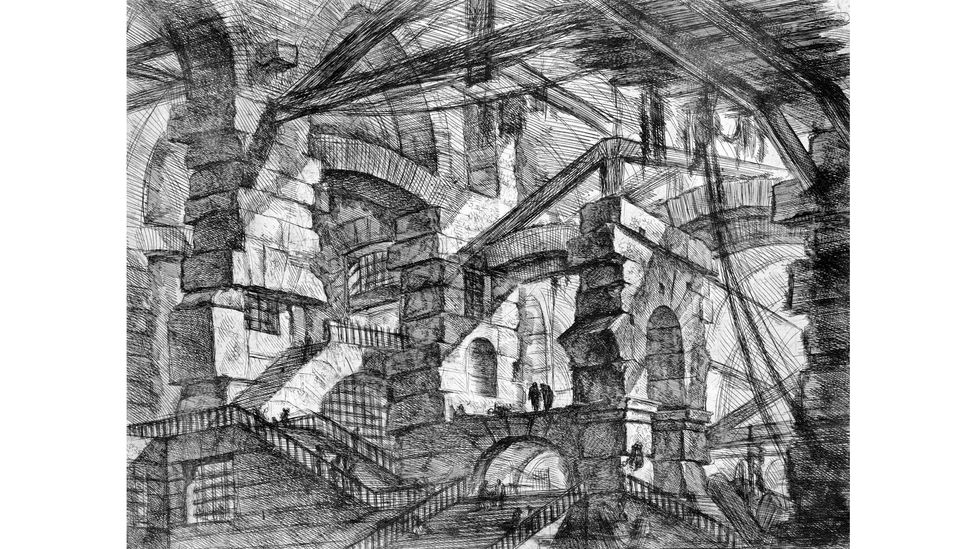

The Gothic arch, Italy, 1749: this print by John Wilton-Ely depicts an imagined architectural feature from an etching by the Italian artist Giovanni Battista Piranesi

Now we have Piranesi, a book that isn’t actually about the 18th-Century Italian artist known for his densely intriguing representations of weird (very weird) prison spaces where architecture ties itself in knots. Clarke’s title is merely a witty allusion, but it is incredibly suggestive. Piranesi (the book) is difficult to describe without making a mess of its intricate puzzling plot, but here there are also fantastical spaces that underlie the real and reflect it (or which the real reflects) in distorted and beautiful ways. It is a story about an amnesiac man who is lost in an immense ruined Classical ‘house’ with countless rooms, some partly underwater, others full of birds or gusts of wind and cloud. The book might start out like an intellectual exercise, but if you’re patient with it you find that it isn’t. It turns into a warm book about losing and finding oneself; about what humanity could have lost in the process of becoming rational.

Containing multitudes

Both of Clarke’s novels have an element of the labyrinthine, of impossible geometries or hidden infinities that one has to find one’s way through. In both the Jordan and Miller interviews, and elsewhere, she has talked about her influences. As a child she adored CS Lewis’s Narnia books, and especially The Magician’s Nephew. (A quotation from The Magician’s Nephew is one of the epigraphs of Piranesi.) Later in life she read and was impressed by Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings. When she was in her 20s, she did a night class on Borges.

From Tolkien she may have imbibed the density and complexity of his use of fantasy tropes (a project so vast that it included the construction of more than 15 languages), as well as his gothic, grown-up sorceries. Above all, Tolkien took fantasy seriously. Possibly too seriously. Then we have Narnia: an immense magical multiverse reached through portals such as a wardrobe and peopled with fauns, dwarves, winged horses, talking animals, witches, etc. Piranesi’s (the Clarke character’s) favourite statue is a faun reminiscent of Mr Tumnus from the Narnia books. To pass through a portal to this mystical realm is to risk getting trapped and never finding one’s way back – or finding one doesn’t want to go back. Piranesi seems to be a prisoner in his house of infinite rooms, through which he wanders.

The labyrinth at the Chateau de Villandry, Indre-et-Loire, France (Credit: Getty Images)

Borges specialised in short stories that fold in on themselves, that spiral, misidentify, mislead, magnify, falsify. His games with meaning are located in fantasy worlds, imagined realms tied to the unconscious. In his preface to the Penguin edition of Borges stories, Labyrinths, the writer Andre Maurois talks about the “interplay of the mirrors and mazes… of thought”; “In all these stories we find roads that fork, corridors that lead nowhere… and so on as far as the eye can see.” Clarke refers particularly to the story The House of Asterion (collected in the Labyrinths volume), which poignantly riffs on the myth of the Minotaur and the maze, and is clearly one of the inspirations for Clarke’s book Piranesi. Asterion declares: “All the parts of my house are repeated many times, any place is another place… The house is the same size as the world; or rather, it is the world.”

One sees these themes – the maze of reason and language, the unravelling of sense – in many of the great modernist and postmodernist writers. In Franz Kafka, Alain Robbe-Grillet, Italo Calvino, and Borges there is a spiral, a tailspin of sense as the mind of the author ambivalently becomes lost in meaning. They all love the metaphor of the labyrinth. Robbe-Grillet’s novel In the Labyrinth (1959), for example, attacks the idea of what an author can know and suggests that, however hard we concentrate, even our simplest perceptions are shifting. A wounded soldier is fleeing in a town whose unfamiliarity becomes dreamlike; are his desperate efforts to navigate to safety not directly equivalent to those of the reader and writer to find meaning? (The soldier dies.)

The fear/fun duality of being trapped in a maze is on the mind of the Japanese writer Haruki Murakami, in for instance Kafka On the Shore (2002), a book that has been described as a “metaphysical mind-bender“. Murakami writes with a typically late-postmodernist mixture of humour and menace. The presence of the name ‘Kafka’ in the title does not bode well for the characters in the book, who try to find their way through the labyrinth of life. Murakami’s world is stuffed with indeterminacy: things that seem to have urgent significance but actually don’t; or seem ephemeral but actually may be of profound significance. His mazes don’t have a centre, as if the idea of rational solutions were itself a myth. And their baffling architecture is a clue to the mysteries within us. In Kafka On the Shore, the character Kafka’s father’s most famous sculpture is called Labyrinth. Murakami writes: “Things outside you are projections of what’s inside you, and what’s inside you is a projection of what’s outside. So when you step into the labyrinth outside you, at the same time you’re stepping into the labyrinth inside.”

The benefits of being lost

In Red Thread: On Mazes and Labyrinths (2018), Charlotte Higgins’ enchanting history of, and meditation on, labyrinths, she talks about their duality of meaning: “Like the creature that inhabits it [the Minotaur], the labyrinth has two natures. On the one hand it conveys beauty, pattern and order; on the other, chaos, fear and bewilderment.” The dream-like qualities of the labyrinth make it joyful and disturbing at the same time.

When we speak about labyrinths, Higgins elaborates on their dual nature: “They hold the pleasures of both pattern and chaos, order and terror. Seen from outside, from above, they satisfy with their neat and pleasing designs; from inside, though, they are confounding and confusing spaces that implicate and constrict the body. Still, however disorienting a labyrinth or maze might be from the inside, there remains the comfort that they are human-made, that they are capable of being decoded and navigated, that being lost inside a maze is only a temporary terror.”

The Minotaur from the Theseus myth, pottery, circa 515 BCE from the National Archaeological Museum of Spain, Madrid (Credit: Getty Images)

Higgins begins from the ancient myth in which Theseus, a hero, attempts to enter a labyrinth and kill a man-eating monster that is half-man and half-bull. (She relates to me how as a child she was lucky enough to be taken to Knossos, in Crete, the real place at the heart of the Minotaur myth. “The place entered my imagination,” she says.) Because the labyrinth is vast and few people find their way back out, Theseus’s lover, Ariadne, gives him a ball of red thread to mark his way by unwinding it behind him. The Middle English word ‘clew’, meaning a ball of thread, has given us our word ‘clue’.

Her book winds its way through the history of mazes – her favourite is the library-labyrinth in Umberto Eco’s novel The Name of the Rose (1980) – but it also suggests that life has a weird geometry, and Higgins leads us along some of the switchbacks, spirals, and dead ends of her own. The path to knowledge is involuted, perhaps irrational. And although the colour red is a key motif in the design of her book, we might not find our way back out.

The labyrinth in Piranesi, writes Clarke, “plays tricks on the mind. It makes people forget things. If you’re not careful it can unpick your entire personality”. The ancient labyrinths were symbols of losing your way and perhaps losing everything. We moderns are more ambivalent – mightn’t loss of personality be a good thing? Certainly in Clarke’s Piranesi, the dissolution of self by some larger, older indeterminate source of meaning is shown to be a good thing. Wandering in the labyrinth without a goal is a good thing, to be revelled in: “The Beauty of the House is immeasurable, its Kindness infinite.” As Clarke told The New Yorker, describing the book she’s now working on, “at the centre of things, there’s a secret or mystery, and it is joyful”.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.