Filmgoers have always been thrilled by characters who break society’s rules. But forget James Dean and Marlon Brando – the real icons of rebellion lie elsewhere, writes Kaleem Aftab.

W

When La Haine premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in 1995, it made an immediate impact. A searing study of working-class Parisian youth living in the city’s housing projects, it earned rave reviews, with Variety calling it “an extremely intelligent take on an idiotic reality” and the then 27-year-old Mathieu Kassovitz winning Best Director for what was only his second film.

More like this:

– Why we no longer need superheroes

– Five stars for Charlie Kaufman’s latest

However, as is so often the case with the greatest films, La Haine only seems to get even better with each passing year. Covering 24 hours in the life of three men from immigrant families – one black, one Arab, and one Jewish – it stands as an indictment of the worst aspects of French, and more broadly Western, democratic society. It exposes the gap between rich and poor; highlights the racism that consigned those from marginalised backgrounds to live in concrete blocks in suburbs – or banlieues – on the outskirts of the French capital; and, most resonantly right now, depicts the police as instruments of brutality set up to protect the rich white elites.

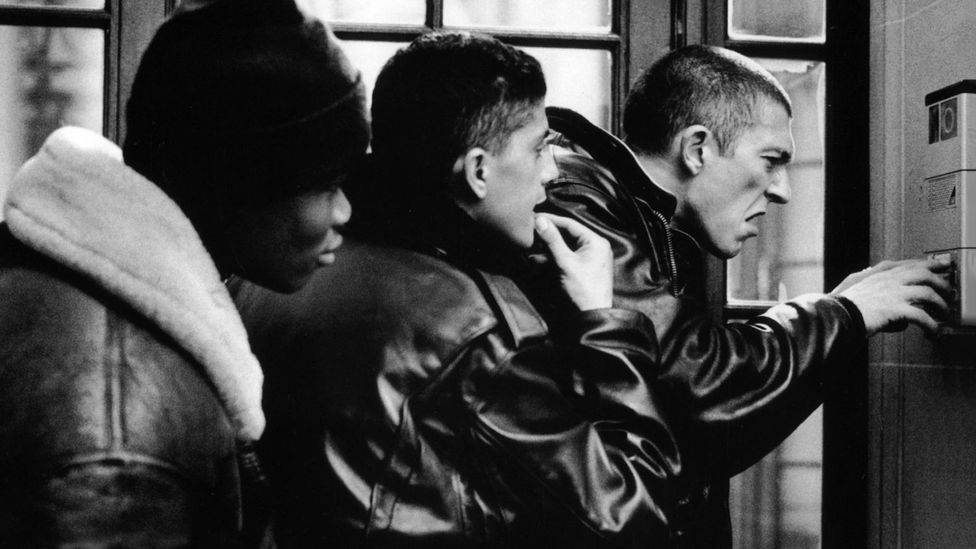

La Haine tells the story of three young men – one black, one Arab, one Jewish – living in a working-class suburb of Paris (Credit: Alamy)

I would argue that if you want to understand Black Lives Matter, watch La Haine. It was a couple of weeks after the murder of George Floyd in May that I was contacted by the British Film Institute asking if I wanted to programme a season of films around the film, to mark its 25th anniversary. With the caveat that my selections had to be available for digital projection because of coronavirus rules, I was given carte blanche to program the season how I wanted. It seemed obvious to me that the season should be about rebellion and screen rebels – but only true ones.

What I mean by ‘true’ rebels are not those that might most immediately come to mind when you cast your mind back through cinema history. That is because for a long time cinema hoodwinked audiences into believing rebellion was about asserting one’s independence with a stylish look and lots of attitude. Whereas La Haine reminded audiences that rebellion could be about something much more profound – overthrowing systemic injustice and the status quo.

Indeed, the success and influence of the film has been so great that since La Haine, the on-screen rebel has been redefined. No longer are the great screen rebels macho white males – but instead they are women, immigrants, or homosexuals, all fighting the white male supremacy with which the old rebels were complicit. La Haine had a huge impact on French society – leading newspapers -to discuss poverty in the outer cities and provoking politicians from President Jacques Chirac to National Front leader Jean-Marie Le Pen to reference it – but it also changed cinema.

An explosive cinematic moment

In one of the most famous opening sequences of cinema, La Haine begins with a shot of the Earth seen from space. Nothing unusual there, until a Molotov cocktail flies towards our planet and an as yet unidentified voiceover provides an anecdote. (“Heard about the guy who fell from a skyscraper? On his way past each floor he says to himself, ‘so far, so good’, but what’s important isn’t the fall, it’s how you land.”) In a dazzling visual effect, the Earth goes up in flames.

Then it shows a montage of rioters clashing with the police. If the camera angles framing the action from the perspective of those battling the police aren’t enough to convince the viewer that the officers of the law are not the heroes here, Bob Marley’s classic resistance song Burnin’ and Lootin’ booms from the soundtrack. The song contains a lyric arguing that policemen wear “uniforms of brutality”.

It’s only after this unapologetically biased beginning that we’re introduced to the three protagonists whose perspective on the world is about to seduce us. And what an introduction it is. It is the night after an uprising that started when a young Arab man was put into a coma by the police. Kassovitz used the 1986 death of student protestor Malik Oussekine as the template for this storyline. But he could have chosen many others. Said (Said Taghmaoui) is first seen writing his name and an expletive on a police van. Hubert (Hubert Kounde) is captured hitting a punchbag in the remains of a gym that was burned to the ground. Then there is Vinz (Vincent Cassel), who wakes up in bed and is hiding a revolver he has taken from a police officer the night before.

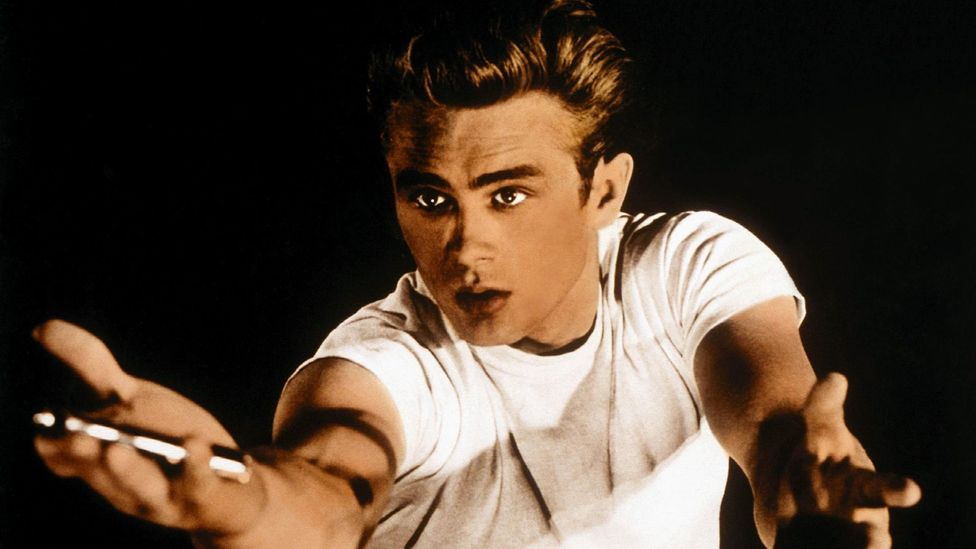

James Dean as Jim Stark in Rebel Without a Cause remains one of Hollywood’s most iconic screen rebels (Credit: Alamy)

It’s no coincidence that Kassovitz’s protagonists are black-blanc-beur (Black-White-Arab). At the time, the term (a play on the red, white and blue tricolour of the French flag) had become one increasingly used by the French media, especially after the Paris riots of 1992, as a shorthand to describe those from les banlieues. It was a not-so-heavily disguised slur against a generation of young, working-class people of colour who were perceived by the white middle-classes as natural born criminals.

However Kassovitz, who started writing La Haine in the aftermath of the events of 1992, determinedly reclaimed the term. Without La Haine it’s unlikely that, three years later, crowds on the Champs Elysees in the aftermath of France’s World Cup win would have chanted black-blanc-beur rather than blue-white-red as a means to celebrate the diverse make-up of members of the winning team. The film had turned a negative racial expression into a joyous one.

From the very beginning, in its depiction of its central trio, La Haine references famous rebels from cinema past. Vinz has a knuckleduster with his name written across it; it’s impossible not to think of Radio Raheem’s Love / Hate jewellery in Spike Lee’s Do The Right Thing, itself a riff on Harry Powell’s knuckle tattoos in Night of the Hunter. More obviously, in one scene, Vinz borrows directly from Robert De Niro’s Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver as he too stands in the front of the mirror asking “you talking to me?”

A vacuous form of revolt

However at the same time, it also radically moved its conception of rebellion far away from the Hollywood stereotype, created in the 1950s and 1960s via a selection of iconic rebel figures in American cinema: think Marlon Brando’s Johnny Strabler on his motorbike in The Wild One (1953), James Dean racing cars in a game of chicken as Jim Stark in Rebel Without a Cause (1955) and Dennis Hopper and his entourage cruising on choppers in Easy Rider (1969).

These macho misfits might still traditionally be seen as the epitome of screen rebellion, but don’t be fooled. Marketers have so easily co-opted them over the years, that they have long ceased to be rebels. What that reflects, though, is an essential vacuousness at the heart of these characters: for behind the fashionable clothes and souped-up motor vehicles they’re not really threatening to change anything and are full of empty rhetoric. Rather, they are just modern cowboys – lone rangers who are not symbols of rebellion in any meaningful sense, but instead paragons of self-indulgent individualism.

Case in point: let’s take the most famous line from the film noir crime film and classic piece of ‘rebel cinema’ The Wild One. Brando’s Strabler is the leader of a motorcycle gang riding through California. In a cafe, where Johnny has been knocked back in his advances by the policeman’s daughter, he’s asked by her friend Mildred, “What are you rebelling against, Johnny?” to which he replies, “Whaddaya got?” Here’s the rub: Johnny’s idea of rebellion is an empty grab for power, an attempt to assert himself as the centre of his society, not to further or overthrow it. He’s just a prototype libertarian.

Taxi Driver’s deranged Vietnam war veteran Travis Bickle is a truly alienated misfit who has never been able to be marketed as cool (Credit: Alamy)

The same is true of the biker anti-heroes of Easy Rider. These pot-smoking hippies have become symbols of rebellion, yet are only rebels in the most anodyne sense of the word, running away from systemic injustice rather than confronting it. As for Rebel Without a Cause, Robert Ebert called it correctly when he said in his 2005 review: “The film has not aged well, and Dean’s performance seems more like marked-down Brando than the birth of an important talent.”

The narcissistic conception of rebellion embodied by the likes of Dean and Brando stands in contrast to the more moral framing of it as an act of resistance against an established government or leader – a framing that goes back cinematically to Sergei Eisenstein’s 1925 classic silent film Battleship Potemkin, which depicts a mutiny that took place in 1905 on an Imperial Russian battleship. In Hollywood’s post-war fixation on white macho rebels, meanwhile, there was little acknowledgement of the sweeping cultural changes that saw women become an essential component of the workforce and African-Americans who had fought alongside their white fellows in World War Two demand the same equality at home. These rebels didn’t represent the true counterculture of the time – that was to be found in the civil rights and feminist movements, and the Stonewall riots led by LGBT people. That’s where real rebellion was happening.

The rebels who found a cause

Mainstream US cinema’s understanding of rebels certainly got more interesting with the arrival of the New Hollywood period in the 1970s. Perhaps the ultimate rebel of this time was Taxi Driver’s deranged Vietnam war veteran Travis Bickle: a truly alienated character who no marketing team has been able to seem like the epitome of cool. Yet what’s interesting and so disturbing about the film is that, in his own perverse way, Bickle has the kind of social conscience that the likes of Johnny Strabler and Jim Stark lack: he is troubled by life in New York and what he sees as the depravity and filth of a lawless society, and so decides to take the law into his own hands.

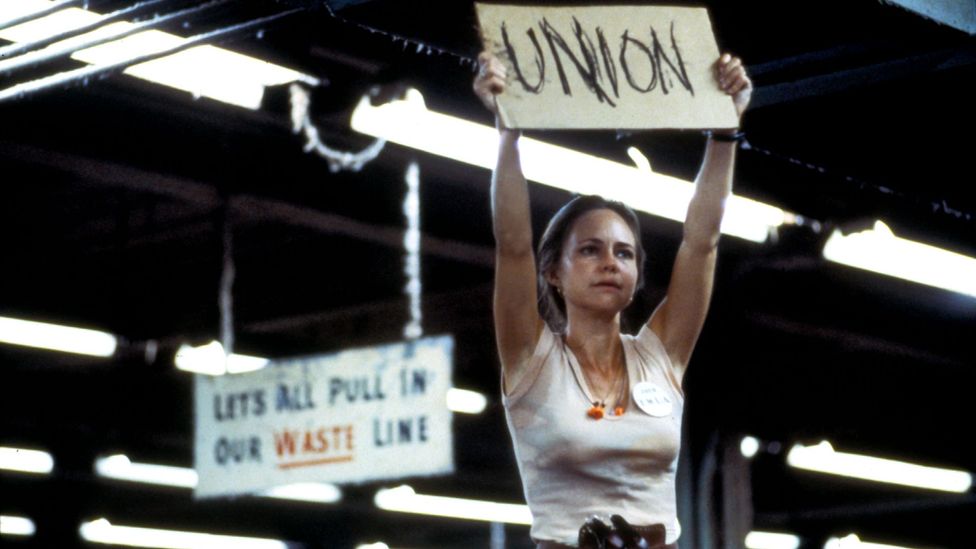

One of the most extraordinary US screen rebels of the era, Sally Field’s Norma Rae in the 1979 film of the same name, is arguably one of the least well remembered. It’s amazing to read old reviews of the film, which condescendingly depict the film as schmaltzy despite the fact that Rae, based on real-life activist Crystal Lee Sutton, is a heroine like few others in popular film: a single, sexually liberated mother with three kids creating a union at her textile factory and aiding the civil rights movement.

While Field won both the Cannes best actress prize and an Oscar for her performance, the film has been relegated to relative obscurity over the years compared to the likes of Rebel without a Cause and The Wild One, probably because it was so ahead of its time and centred on a woman. Thankfully, it seems that its time is now: only last month The New Yorker ran an essay by Naomi Fry championing its ongoing relevance. “On this viewing, what struck me even more strongly, however, was the movie’s suggestion that no struggle can take place alone,” writes Fry. “Norma Rae is heroic, but she comes into her own, as a woman, because she is fighting for class solidarity – a struggle that, in turn, could not happen without a breaking down of long-standing ethnic and racial barriers.” One of the most memorable lines of the film comes when Rae is warned about fraternising with black men and quips, “I’ve never had trouble with black men, only white men.” It’s a film that understands that the most profound act of rebellion is a collective and intersectional one.

Sally Field’s Norma Rae remains one of American cinema’s most extraordinary heroines: a single, sexually liberated mother and union organiser (Credt: Alamy)

In the 1980s, the US embraced Reagan and corporatism and cinema followed suit, quickly forgetting about the rebellious steps made by New Hollywood and instead travelling in the opposite direction, venerating the puffed-up white male action hero pursuing jingoistic goals.

That’s not to say that rebels couldn’t be found, but they were present in less expected milieus, like John Hughes teen movies or the 1986 metropolitan comedy drama She’s Gotta Have It, the debut of a certain Spike Lee, which created the quintessential sexual and romantic rebel in the shape of Tracy Camilla Johns’ polyamorous Nola Darling.

Three years later, Lee then made the ultimate US film of this period about the need for rebellion, Do the Right Thing. It’s a film often seen as of a piece with La Haine because of the way they both deal with racial tensions and urban rioting – though while Lee deals with events leading up to a riot, Kassovitz is more concerned with the aftermath. What’s more, while Do the Right Thing, which shows the fractures and reverberations within a neighbourhood, is a magnificent, sprawling ensemble piece, La Haine channels its rage more tightly through its three lead figures. Iconic rebels for the late 20th Century, they became a template for how to depict rebellious characters to a whole new generation of filmmakers around the world.

Figureheads for a new age of protest

Rewatching the film, what marks Said, Hubert and Vinz out as the purest form of rebels is that they are not attempting to simply escape a system, but rather fundamentally challenge it: they see tackling it head on as their only means of survival. Rebellion was no longer about personal freedom but about overthrowing the power elites.

It says much about the impact of this central trio on the cultural imagination that despite depicting a largely masculine world, La Haine has been a recurring model for women filmmakers making movies about female rebels. In recent years Celine Sciamma’s Girlhood (2015), Houda Benyamina’s Divines (2016) and Maimouna Doucoure’s Cuties (2020) have all nodded to it, being similarly set in les banlieues and featuring minority groups fighting against poverty and racism for a place in society.

Meanwhile Swedish director Gabriela Pichler’s 2018 film Amateurs references it even more overtly: Pichler told me she was directly inspired by scenes from Kassovitz’s film “like the one with the TV team visiting the suburbs filming the three guys and how the reaction looked from the TV-camera POV.” The film tells the story of a small town that has employed marketers to make a promotional video to encourage a German discount supermarket to open up shop. It’s a strategy whose falseness is brought into stark relief when two young kids get out their camera phones and begin making a film highlighting how the town really is – a place where, beneath the white affluent surface, many people of colour struggle in poverty.

New French drama Les Miserables complements La Haine, offering a contemporary take on social unrest in the Paris banlieues (Credit: Alamy)

Far and wide, indeed, La Haine kickstarted a global wave of generational protest cinema. From Fatih Akin’s German-set Short Sharp Shock (1998) right up to 2019 Cannes Jury Prize winner Les Miserables, these combative films have shown the world from the perspective of the racially dispossessed looking to assert themselves. Channelling real anger as they do, these are not films that aim for balance: the characters looking to take down the system are sympathetic, while those seeking to uphold it are invariably corrupt.

Les Miserables is very overtly the offspring of La Haine in that it tells a similar story of social unrest in the Paris banlieues, only this time from the perspective of three policemen – who are, like La Haine’s central trio, from a diverse range of ethnic backgrounds. However, despite this hopeful twist, what writer-director Ladj Ly and his co-screenwriters Giordarno Gederlini and Alexis Manenti show is that the result is depressingly the same. The plot revolves around the officers trying to retrieve filmed footage of a moment of police brutality on camera, which involves them taking the law into their own hands and hunting down a young kid.

What the film powerfully suggests is that a more diverse police force is not a magic bullet, but a more radical overhaul is needed to eradicate systemic injustice. The Black Lives Matter movement this summer led calls to ‘defund the police’, which was not a literal demand about eliminating police departments but a call for a radical overhaul in policing. In the same way, the Molotov cocktail landing on planet Earth in La Haine still resonates as a symbolic provocation that the only way to create lasting positive change is to wipe out what has gone before and start again from scratch. And what can be more rebellious that that?

La Haine is re-released in selected UK cinemas today. The Redefining Rebellion season runs at the BFI, London throughout September.

Love film and TV? Join BBC Culture Film and TV Club on Facebook, a community for cinephiles all over the world.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.