Martin Scorsese’s mob movie is special for many reasons – not least its famous single-take nightclub scene. Hanna Flint delves into the creation of a piece of cinema history.

T

Thirty years ago, Martin Scorsese’s Goodfellas was released and set a new benchmark for innovative storytelling and filmmaking. Adapted from the book Wiseguy by crime journalist Nicholas Pileggi, who also co-wrote the script, the film charts the rise and fall of real-life New York mobster Henry Hill in a powerfully funny, brutal, horrifying and kinetic way. Goodfellas has long been considered one of Scorsese’s greatest ever movies – as the late Roger Ebert had it, “no finer film has ever been made about organised crime” – and part of its greatness comes down to one scene: the Copa shot.

More like this

– Why we should rethink Waterworld

– The world’s greatest screen rebels

– The twisted horror of the US south

Affectionately named after The Copacabana nightclub, where the scene was executed, it is a one-take – a long, continuous shot by a single camera – of just under three minutes that takes its cues from one particular memory in Pileggi’s book offered up by Henry’s wife Karen: “On crowded nights, when people were lined up outside and couldn’t get in,” it reads. “the doormen used to let Henry and our party in through the kitchen, which was filled with Chinese cooks, and we’d go upstairs and sit down immediately.”

The single-take Copa shot tracks the beginning of a night out for mobster Henry Hill and his wife-to-be Karen, as they make their way into the Copacabana club (Credit: Alamy)

Scorsese managed to bring this line to life in seamless fashion but he couldn’t have done it without an exceptional cameraman, Larry McConkey, and the Steadicam, a revolutionary piece of tech that had been invented by cameraman and cinematographer Garrett Brown 15 years earlier. The recording equipment was designed to have the flexibility of a hand-held camera, the stability of a tripod and the fluidity of movement that a dolly (a camera wheeled along a track) provides all at once. Stanley Kubrick employed the Steadicam to achieve the scene in The Shining (1981) where Danny tricycles around the Overlook Hotel and it was also used to acclaim in Marathon Man (1976), Rocky (1976) and Bound for Glory (1976), which is how McConkey was introduced to it. “It blew me away, it was extraordinary,” he tells BBC Culture. “I thought somebody made something for me because I’d spent hours and hours trying to train myself how to walk more smoothly.”

McConkey was trained up by Brown himself. “Larry was my first ‘student’ in 1977 and his mastery of our ‘noble instrument’ remains intensely gratifying,” the inventor tells BBC Culture. The lessons took place at Brown’s own townhouse in Philadelphia where, according to McConkey, he told his student that if he hit any of the walls “his wife would kill them”. So he got his pupil to turn the camera’s monitor off and manoeuvre the equipment blind. This would allow him to focus on where he wanted the shot to be and move the camera through space accordingly to frame it. McConkey says, “that one week [with Brown] was worth at least two years’ experience on your own,” and as the equipment grew increasingly popular, the cameraman quickly became the go-to person for shooting with the Steadicam.

How it came together

“This is going to be a disaster.”

Those were the words running through McConkey’s mind as Scorsese walked him through his idea for a night club scene on the New York set of Goodfellas. It was a late afternoon during the summer of 1989 and production was in full swing. The director had called McConkey a day or two earlier. The cameraman had impressed Scorsese with his Steadicam skill on his previous movie, 1985’s After Hours, and wanted to hire him for a few days. But it wasn’t until McConkey arrived on set that he had any clue of what Scorsese wanted him to do.

The filmmaker met the cameraman near to The Copacabana where the scene – which would later become known as the Copa shot – was to take place. Ray Liotta and Lorraine Bracco, the actors playing Henry and his then wife-to-be Karen, cinematographer Michael Ballhaus, McConkey, an assistant director and the script supervisor were gathered before Scorsese, who explained his vision. He wanted to shoot a continuous take that would follow Henry and Karen from the moment they arrived at the club to the moment they were seated inside, capturing every step of their journey in between. “The rehearsal began when he showed us he wanted to start on a close-up of a tip being handed to the guy parking Henry’s car,” McConkey recalls. “There were no storyboards, just him talking.”

The group followed Scorsese across the road and into the club. They listened to him explain how the camera would follow Henry and Karen as they navigated their way through the backstage of the venue. The director tried to lead them past the kitchen but Ballhaus demanded they walked through it. “He said, ‘we’ve got to go into the kitchen because the light is a different colour’,” McConkey recalls. “For contrast!” So Scorsese adjusted his route and soon they arrived in the main ballroom where “very colourful choreography had been worked out” to get the couple to their final seated position.

Before Goodfellas, the most striking use of the Steadicam was the scene in The Shining (1981) where Danny tricycles around the Overlook Hotel (Credit: Alamy)

McConkey was nervous. The Steadicam is not an easy piece of equipment to use and even with his years of training, navigating that route would be his toughest challenge yet. “I’ve always maintained that it should have been called the ‘smooth cam’ because it’s anything but steady,” he says. “Marty looks at me and says, ‘Okay?’ I said, with my eyes wide, ‘Okay.'”

Creative tricks

Scorsese left him to it but Liotta kindly volunteered to walk through the scene to work out how they would stage it and locate potential technical problems. “If it’s one continuous shot then it all has to have the right rhythm, it has to have meaning and you have to build suspense,” McConkey says. He noticed a problem straight away when Henry and Karen descend the stairs after entering the club’s back door. The camera would be too close to the tops of their heads, which “wasn’t photogenic”, so he paused at moments to create a wider shot but needed Liotta to stall before he then rounded the corner into the club’s corridors so he could catch up and get closer again. The actor decided he would tip the doorman to give McConkey that time, and offered up similarly creative solutions for other points in the take. “Ray made sure that anything I asked him to do that was mechanical became a key part of the character,” McConkey recalls.

All the dialogue spoken in the Copa shot, up until Henry and Karen’s ballroom entrance, was improvised in rehearsal by Liotta and McConkey as a way to show more of the character’s faces, give the camera time to set up a new angle or even disguise the fact that when the couple are in the kitchen, they are walking out through the same door they entered in.

“The dialogue between Ray and Lorraine Bracco and the artful asides with guards and employees cleverly helped show the actors faces back to the following camera,” Brown remarks. “And the invisible double-switcheroo twice around the kitchen extended the proceedings and made them wonderfully kinetic.”

Scorsese “ceded a lot of responsibility” to McConkey, he says, so the cameraman put himself into the mind of the audience, and “built into the shot a desire to see something and pay it off by doing it.” He was editing in real-time, reframing angles, movements and frames as he rehearsed several times with Liotta. He worked with “every single one of the extras” so there were no mistakes with people looking at the camera or missing their cue before they committed it to film. Attaching a video recorder on top of the Steadicam allowed him to get a crude idea of how the long take would appear and give something for Scorsese to look at for approval.

“I’m like, ‘oh my god I’ve just taken over this film, what is he gonna think of it’?” McConkey recalls of the moment he showed the director the rehearsal tape. “Marty watches it and goes, ‘no, no, no!’ [and] I think ‘that’s the end of my career’ but Marty, who was grabbing oxygen from a canister because he had asthma, said, ‘the table [in the ballroom], when [it is brought out by a waiter for Henry and Karen], it’s got to be flying right out of nowhere.’ Marty used to come here with his parents, and he said one time it was like magic when the tables came flying out.”

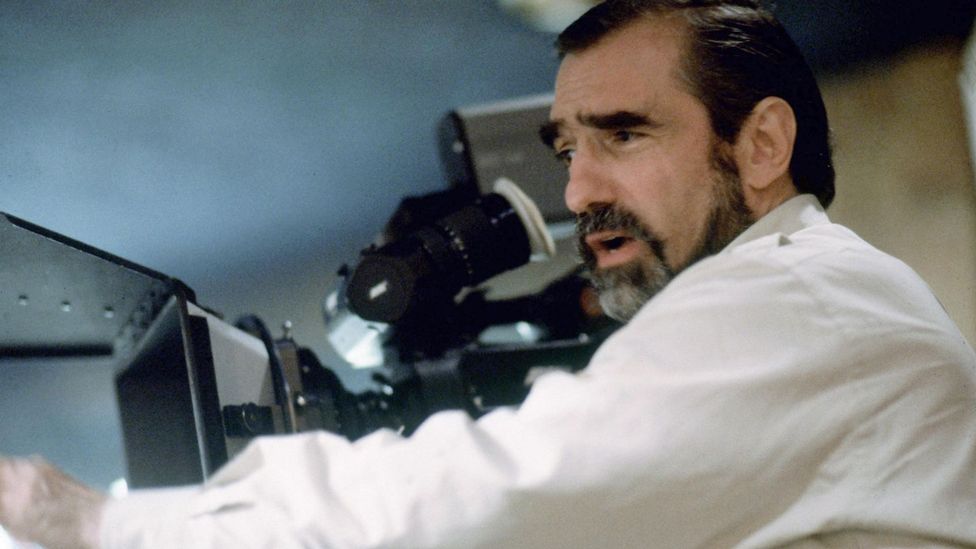

When shooting the scene, director Martin Scorsese ceded a lot of responsibility to cameraman Larry McConkey (Credit: Alamy)

So after fixing Scorsese’s note, they shot the scene “seven or eight times” and by the seventh take, they had choreographed it to near perfection. “Take seven, that’s where it all comes together because the actors are finding the rhythms and I begin to predict what they’re about to do and when it’s going to happen,” McConkey explains. “Because with Steadicam if something happens suddenly it can be unsettling.”

But McConkey was a pro and out of eight takes, two were circled for consideration for the final edit. However, the one he preferred wasn’t used. “It was a minor thing, but I’d given the cook a line,” he explains. “But he was an [non-speaking] extra so then they’d have [had] to pay him like an actor.”

The magic of the end product

The result of that half-day’s work, a “long half-day” as McConkey recalls it, was an exhilarating piece of cinema that helped to push Henry’s romantic plot forward and further establish his character. In one uninterrupted take, Henry’s local celebrity status is slowly revealed to Karen with the audience following closely behind, watching every exuberant greeting and handshake delivering an obscene amount of tips. The Copa shot stands out in a movie otherwise charged with frenetic energy thanks to a mix of quick edits, freeze frames, location switches and extensive use of narration delivered by the film’s lead.

The Copa shot, instead, is a smooth continuous ride with minimal dialogue that steadily builds to a magical conclusion. There’s a romance to it; the fluid motion of the camera’s eye adds to the seduction of Karen, as well as the audience watching. It makes us feel we are right there with Karen as Henry sweeps her off her feet not only by showing her his importance, but demonstrating her importance to him, by ensuring she has the best date of her life with no expense spared.

Brown said he felt “pure joy” when he first watched the Copa shot. “I had people calling and emailing about it long before we finally got to see it,” he explains. “It wasn’t just the uncut length — it was perfectly designed and executed to propel the narrative and establish Ray Liotta’s character.”

Goodfellas put the one-take on the cinematic map like no other film. It had been done in the past by the likes of Orson Welles and Alfred Hitchcock but, as McConkey points out, it “was a massive undertaking” before the Steadicam was invented. The Copa shot was a landmark moment showing what filmmakers could achieve if they had the vision. Many directors have since paid a not-so-subtle homage to it, such as Paul Thomas Anderson in his breakthrough 1997 film Boogie Nights, which opens with one continuous take in a nightclub. In the 2012 drama The Place Beyond the Pines, Derek Cianfrance offers an uninterrupted shot to introduce Ryan Gosling’s motorcycle stunt driver, while in the celebrated 2001 episode of Buffy the Vampire Slayer, The Body, a one-shot is used to highlight the panic of the lead finding her mother dead.

Paul Thomas Anderson (centre) is among the directors to have paid homage to the Copa shot with the opening sequence of his 1997 film Boogie Nights (Credit: Alamy)

Alfonso Cuaron, Joe Wright, Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu, Sam Levinson and of course 1917’s Sam Mendes, have also added their names to the one-shot canon – as have hundreds of other filmmakers since 1990. But with so many directors and cinematographers trying to replicate the Copa shot’s greatness, is there a danger that it is becoming overused?

“I don’t think so,” says Brown. “No more than the cut, the dissolve [or] the fade. There are times when such arbitrary continuousness sustains shocking intimacy with the performers and brings us face to face with the gripping, unblinking tension of passing time.”

So is the Copa shot the greatest shot in cinematic history? Well, it’s long been considered one of the greatest, appearing on several lists and rankings placing it up there with the best. “That Copa shot is still famous among moviegoers and legendary for thousands of Steadicam operators,” Brown says, “and for good reason: it’s perfect!”

For McConkey, who went on to shoot Brian De Palma’s famous 12-minute opening one-take for his 1998 thriller Snake Eyes and was the Steadicam operator on such films as Carlito’s Way (1993), The Silence of the Lambs (1991) and Natural Born Killers (1994), the Copa shot is the thing on his CV that continues to resonate most.

“I remember once, being in a cab in New York, and the driver asked what I did. I said, ‘I’m a Steadicam operator; you may not have heard of them,'” he says. “The driver said, ‘oh yeah I know, hey that Goodfellas shot is that thing.’ I said, ‘Yeah, I did that.'”

Love film and TV? Join BBC Culture Film and TV Club on Facebook, a community for cinephiles all over the world.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.