After going straight to TV, The Last Seduction proved such a hit it was released in cinemas – and still has an avid following today, writes Anna Smith.

I

In 1994, the term ‘straight to TV movie’ was used mostly as an insult. So when a small film called The Last Seduction premiered on HBO, nobody expected much. But those who caught it were floored by a darkly comic noir thriller with a knockout performance from Linda Fiorentino as Bridget Gregory. Bridget is a smart-talking New Yorker who hits ‘cow country’ with a suitcase of cash her husband Clay (Bill Pullman) had acquired in a drug deal. Advised to lie low for a while, Bridget shacks up with smitten local Mike (Peter Berg) and uses him to enact a devious plan. Directed by John Dahl and written by Steve Barancik, The Last Seduction is bitterly funny and deliciously clever – the razor-sharp dialogue is loaded with one-liners. It’s also sexy in a way that appeals to both women and men. With its manipulative femme fatale, it touches on similar themes to the big-budget Basic Instinct – but many believe it does it much better.

More like this:

– The most outrageous film ever made?

– The classic that’s saved lives

– The film that exposed our misogynistic culture

Thanks to a rapid cult following, The Last Seduction made it into cinemas, and onto many a video, then DVD, then Blu Ray shelf, including my own. It was listed as one of ‘the greatest crime films of all time‘. It’s been analysed in books, essays and think pieces – one or two of them written by me. Its critical consensus is 94% positive on reviews aggregator sites. And yet, it’s still a cult film rather than a mainstream hit – and one with a suitably troubled past.

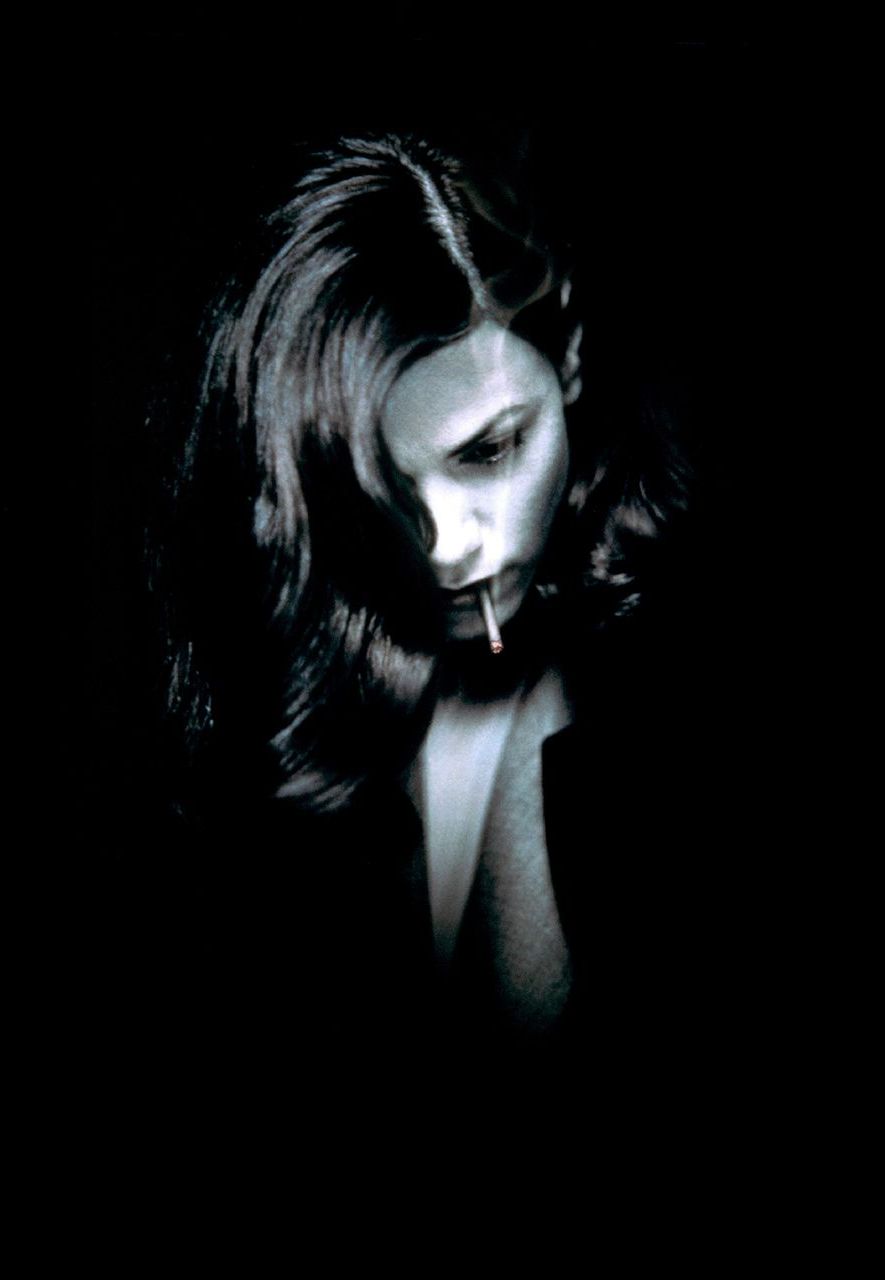

Although The Last Seduction went straight to TV at first, it gained a cult following and was later released in cinemas (Credit: Alamy)

The Last Seduction’s journey to the screen started smoothly, says Stacy Kramer, the film’s executive in charge of development. “I was sent this script out of the blue. It was by a writer none of us had heard of, but the script was perfect, it was kind of amazing. Steve had done all the work. We were able to move forward into pre-production without a lot of pre-writing and stars came aboard immediately. Everybody loved it, so it was one of those projects that seemed blessed from the beginning. Then things got a little hairy…”

The company she was working for was taken over by a businessman who wanted to pull the project. “He really didn’t understand moviemaking at all. He decided we weren’t gonna make it. He decided it was getting too expensive… he wanted to scrap it, and I basically burst into tears in his office because it seemed like the only way to really impact him. It was very manipulative, but it worked.”

In control

Calculated tears are a move worthy of the film’s lead character Bridget, a quick-thinking profiler who knows exactly how to get results from the person in front of her. She issues orders to Mike in the manner of a dominatrix (in and out of bed), but she also knows when he needs to feel manly – so she feigns vulnerability. City slicker Bridget exploits everyone’s weaknesses and prejudices, even harnessing the casual racism of small-town cops to shake off a black private investigator on her tail. She is what lawyer Frank (JT Walsh) calls “a self-serving bitch” – a ruthless, superior psychologist who knows she’s smarter than everyone else in the room.

Bridget was an unusual character: a female allowed to be evil and strong (Credit: Alamy)

With brazen self-confidence, a knowing smile and a husky voice, Linda Fiorentino spoke to audiences seeking an unconventional heroine. It was a ‘dream role’ for the actress, according to a 1995 interview with Roger Ebert. “After I read that script, I was in Arizona and I got in a car and drove six hours to get to the meeting because I had never read anything so unique in terms of a female character. And I walked in the meeting with John Dahl, the director, and I said, ‘John, you are not allowed to hire anyone but me for this film.’ And I wasn’t kidding.”

“Linda captured the role,” agrees Kramer. “We had been to a whole list of people before actually settling on Linda – they had wanted to get a huge star. A lot of those people said no because they thought that character was too unlikable. So at that time in the 90s, we were just not gonna get an actress who was willing to take that kind of role. That’s one of the problems facing women in the industry – men can toggle back and forth between unlikable: think of the Russell Crowes. But those women have to take those things into consideration when taking a role.”

Fiorentino thought differently. “I think there is a certain catharsis in being as evil as you can and getting away with it, and getting paid for it,” she told Ebert. “But I think I’ve done it enough now.”

“It’s just so rare to see such a powerful character that just was so charismatic – you really couldn’t take your eyes off her,” says Kramer. “I still can’t even think of that many female characters like that. She was so complex, she was evil, but it was so nuanced in so many ways. She could be sort of evil with glee. It’s just so rare to see female antagonists. We’re not really allowed to just have them – they get punished. But she was able to be strong.”

While Bridget was a powerful female character unlike many others, The Last Seduction’s writer never meant her to be a feminist icon (Credit: Alamy)

Among those fighting to keep the film’s triumphant ending was writer Barancik. He tells me when he knew Bridget had become a cult figure. “In the early days of the internet, I noticed women online who were taking Bridget Gregory as their screen name,” he says. “There were other hints that some women were taking inspiration from her, shall we say, choices. Those may have been early indications that the movie had struck some sort of cultish nerve.”

It’s here that I have to admit that my own screen name was once Wendy Kroy – Bridget’s pseudonym inspired by New York in mirror writing. But while I remain in awe of her sharp mind and cool decisiveness, I have felt a little uncomfortable about this femme fatale as a feminist icon. In moral terms, she’s no role model and you’d imagine she’d be as ready to use women as men if she had to, although other women rarely come into the picture.

It turns out Barancik shares my reservations. “I’d be lying if I said I intended my soulless, murdering character to turn into a feminist icon,” he says. “Here’s the feminist part of it I intended: I wrote her to be the protagonist, not the femme fatale seen through the sex-struck, lovesick sap’s eyes. I realised halfway through the drafting process that it was a lot more interesting being privy to her machinations than blind to them.”

Although some thought Fiorentino’s performance was worthy of an Oscar nomination, she was ineligible, because the film was shown on TV before being released in cinemas

He’s hit the nail on the head. And it’s what Kramer was fighting for. “It was exhilarating, but it was a fight. It was a fight with a lot of white men, who didn’t really understand the role at all. I was 29 at the time and I had to fight for every last crumb.” You can imagine Kramer’s dismay when the film she’d intended for theatrical releases was sold to HBO, making it ineligible for Oscar glory, too. “I didn’t even know. They didn’t tell me. I ran the creative team, but largely the business team operated completely separately. Nobody was watching movies on HBO and I thought it was a death knell, you know? We just assumed it was going to fade into oblivion.”

But of course, it did not. And the love for this cult film lives on. Only last year, The Last Seduction featured in the BFI’s ‘Playing the Bitch’ season, alongside Gone Girl and Death Becomes Her. When I chose to discuss The Last Seduction in an episode of Girls On Film podcast, I had an unusually rapturous response from my younger film critic guests. “Fiorentino in this film is Barbara Stanwyck and Bette Davis and Lauren Bacall and Veronica Lake wrapped into one, with some weaponry,” raved Pamela Hutchinson. “It’s neo-noir and it shows how one of the most interesting spaces for female-led film has been reinterpretations of film noir where you give women more agency in the film.” As Kramer says, “I don’t think I’ve ever been part of anything [else] like that.”

So where are the cast and crew now? Fiorentino appeared in Men in Black and Dogma but has largely dropped out of the public eye – her last movie was 2009’s Once More with Feeling. Berg became a Hollywood director, making macho films such as Friday Night Lights, Battleship and Deepwater Horizon. Pullman is still busy acting with that mischievous glint in his eye. Dahl directs in television, while Kramer is a writer and producer. After The Last Seduction, she went to work at Fox, where she hired Barancik to write two screenplays – both “amazing”. Fox decided not to make either. The man who created Bridget Gregory went on to write children’s books, and modestly says, “I’m just a former screenwriter who teaches school in Tucson, Arizona.” But he will always have The Last Seduction – and so will we.

Love film and TV? Join BBC Culture Film and TV Club on Facebook, a community for cinephiles all over the world.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.