A new album documents the life and death of Victor Jara , a Chilean folk singer who became an international icon of resistance, writes Dorian Lynskey.

V

Victor Jara named his last song after the place where he spent his final days: Estadio Chile, an indoor sports complex in Santiago. He wrote it on 16 September 1973, five days after a military coup led by General Augusto Pinochet brought down the socialist government of Chile’s president Salvador Allende. Jara had been arrested the day after the coup and held in the stadium that had become an ad hoc detention centre for around 5,000 supporters of Allende’s Popular Unity alliance.

More like this:

– The images that fought Fascism

– Powerful images of Hong Kong protests

– Pop music’s greatest philosopher

There are many conflicting accounts of Jara’s last days but the 2019 Netflix documentary Massacre at the Stadium pieces together a convincing narrative. As a famous musician and prominent supporter of Allende, Jara was swiftly recognised on his way into the stadium. An army officer threw a lit cigarette on the ground, made Jara crawl for it, then stamped on his wrists. Jara was first separated from the other detainees, then beaten and tortured in the bowels of the stadium. At one point, he defiantly sang Venceremos (We Will Win), Allende’s 1970 election anthem, through split lips. On the morning of the 16th, according to a fellow detainee, Jara asked for a pen and notebook and scribbled the lyrics to Estadio Chile, which were later smuggled out of the stadium: “How hard it is to sing when I must sing of horror/ Horror which I am living, horror which I am dying.” Two hours later, he was shot dead, then his body was riddled with machine-gun bullets and dumped in the street. He was 40.

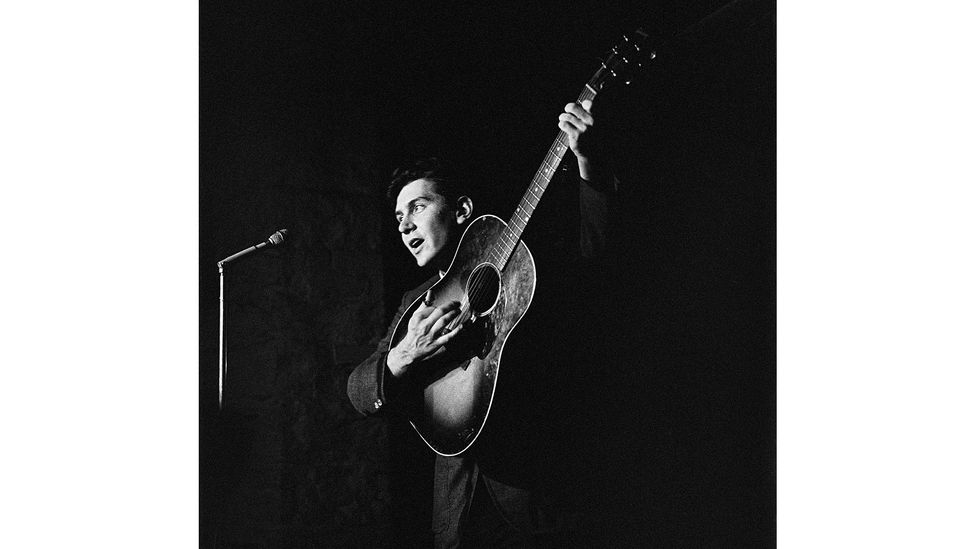

Jara (pictured right) wrote the song Venceremos, a Chilean socialist anthem that means ‘We Will Win’ (Credit: Getty Images)

Victor Lidio Jara Martinez didn’t sing in English, nor did his songs substantially influence Western music, but the manner of his death, the symbolic silencing of his music, made him an international symbol of resistance: “[a] cross between Bob Dylan and Martin Luther King,” as someone says in the Netflix documentary. Dylan himself headlined a tribute concert in New York a few months after the coup. Since then, Jara has been commemorated in dozens of songs in several languages, most famously The Clash’s Washington Bullets (“Please remember Victor Jara in the Santiago stadium”) and U2’s One Tree Hill (“You know his blood still cries from the ground”). Now James Dean Bradfield of the Manic Street Preachers has recorded a whole album about Jara’s life and death, Even in Exile, along with a three-part podcast series, Inspired by Jara, with guests including Charlie Burchill from Simple Minds, the Labour MP Kevin Brennan and Emma Thompson, who tried for years to make a biopic.

“He died defiantly but with grace, too,” Bradfield tells BBC Culture. “It takes your breath away every time.” Yet Bradfield wanted his songs, with lyrics by poet and playwright Patrick Jones, to illuminate Jara’s life as well as his death. “If you just focus on his death, you ignore the journey, you ignore the ambition, you ignore the songs, and you kind of ignore Chile. That immovable image of his murder can be a red herring.”

Bradfield first discovered Jara via The Clash as a teenager and learned more about the coup from the 1982 film Missing, so when he first heard one of his songs, Manifiesto, he was taken aback by its tenderness. “The truth isn’t rammed down your throat; it floats to you like a dream,” he says. “That wasn’t what I expected at all. He’s one of the only truly Marxist musicians but he doesn’t sound Marxist at all to me.”

James Dean Bradfield of the Manic Street Preachers has recorded an album about Jara’s life and death, Even in Exile (Credit: Getty Images)

In 2016 Patrick Jones, whose brother is Bradfield’s bandmate Nicky Wire, discovered two vinyl compilations of Jara songs in a Cardiff charity shop and became obsessed, writing dozens of poems about Jara’s life. The picture that emerged from documentaries and the 1983 memoir written by Jara’s widow Joan was of a charismatic revolutionary who was also a gentle family man. “I felt I knew him,” says Jones. “I felt he could come round and sing a song and then he’d be in the kitchen cooking.” The story of the coup, meanwhile, seemed to Jones to resonate with recent political upheavals. “I was thinking, I can’t believe it’s nearly 50 years since this happened and here we go again with the rise of the right in America, Hungary, Brazil…” After he shared his fascination with Bradfield, the poems evolved into songs and, eventually, an entire concept album which spans Jara’s life from his rural childhood (The Boy from the Plantation) to his final hours (The Last Song). “I started distilling these more universal, ranty poems into something a bit more personal,” says Jones.

Bradfield wonders if Jara’s counterintuitive blend of radicalism and sensitivity stemmed in part from the crucial influence of three women in his life. While his father was an illiterate farmer, his mother was a well-read musician who performed at local weddings, baptisms and funerals. After considering the priesthood, Jara studied theatre, which took him to Russia, Cuba, Britain and the US and introduced him to Joan, an English dance teacher living in Chile. At the same time, he pursued songwriting under the wing of the folklorist Violeta Parra, the mother of the Nueva Cancion Chilena (New Chilean Song) movement. Groups such as Inti-Illimani and Quilapayun combined traditional Chilean folk music with topical political messages. Music replaced theatre as Jara’s vocation. At the first Nueva Cancion Chilena festival in 1969, held in the same stadium where he would later die, he won first prize.

‘A naked truth’

“We’ve had enough of that music that doesn’t speak to us, that entertains us only for a moment but leaves us empty,” Jara once said. “We began to create a new kind of song. It was music that was born out of total necessity.” He may have been blessed with a rock star’s good looks and charisma but he scorned Western protest singers, compromised by money and fame in a trivialised, commercialised culture. A dedicated communist, he preferred the term ‘revolutionary song’.

“They didn’t respect that rock ‘n’ roll culture,” Bradfield says of the Nueva Cancion movement. “They said these protest singers are false prophets. So when you’re making a record like mine you think, ‘God this is something they probably wouldn’t like!’ But you can’t let that stop you, can you?”

Joan Jara – pictured in 2017 – described her husband in her 1983 memoir as a gentle family man as well as a charismatic revolutionary (Credit: Getty Images)

Some of Jara’s songs were sharply topical. In Preguntas por Puerto Montt (Questions About Puerto Montt), he bravely called out the Minister of the Interior after Chilean police killed 10 villagers during a brutal eviction of squatters in 1969. Other songs, such as Bradfield’s favourite Luchin, were tender, empathetic stories of rural working-class lives. Manifiesto, one of Jara’s last recordings, was an anthem that sounded like a ballad and became a prophecy: “A song has meaning/ When it beats in the veins/ Of a man who will die singing.”

“When I listen to him, even through the language barrier, I get hypnotised,” says Bradfield. “There’s a naked truth that’s hard to beat.” Still, he says, the contrast between the form and content of Jara’s songs can be disorientating. He cites El Derecho de Vivir en Paz (The Right to Live in Peace), which Jara dedicated to the North Vietnamese leader Ho Chi Minh. “You get entranced and then think, ‘Ho Chi Minh?!'” he laughs. “I feel like he emotionally tricked me into it with his music.”

Jara was a polarising figure in a polarised country. At one university show he was pelted with stones and pursued by an anti-communist mob, but he was hugely popular with Allende and his supporters, writing Venceremos for Popular Unity’s election campaign. After winning the presidency in September 1970, Allende made a victory speech in front of a banner reading: ‘You can’t have a revolution without songs’. That isn’t always true but it was true in Chile. “They were on the radio and they were on the television,” Joan Jara told the NME in 1975. “The song movement was a tremendous weapon… in the fight to make people aware.”

After the US singer-songwriter Phil Ochs met Jara in Chile in 1971, he told his brother: ‘I just met the real thing (Credit: Getty Images)

Jara’s courage and conviction were daunting even before his death. After the US singer-songwriter Phil Ochs met Jara in Chile in 1971, he told his brother: “I just met the real thing. Pete Seeger and I are nothing compared to this. I mean, here’s a man who really is what he’s saying.” While US protest singers could be heckled or censored for their music and activism, Jara was murdered for his. “It’s almost too much to take on board isn’t it?” says Jones. “We think we have protest and oppression in Britain but when you think you could be literally pulled off the street and imprisoned and killed…”

‘A warning from history’

While making Even in Exile, Bradfield was reminded of Nicky Wire’s original lyrics for the Manic Street Preachers’ 1998 hit If You Tolerate This Your Children Will Be Next.”It started out as a self-accusation: you may engage in politics, you may write about it, but there’s no way you will ever be able to sacrifice what these people sacrificed so look in the mirror and remember that. How many convictions do you have, truly? [Jara] actually did die for what he believed in.” He discusses this sense of inferiority on the podcast with the veteran singer-songwriter and activist Holly Near. “She said, ‘Oh he had an ego, don’t worry about it’. That brought him back down to being a normal person again. Of course, nobody is ever a saint.”

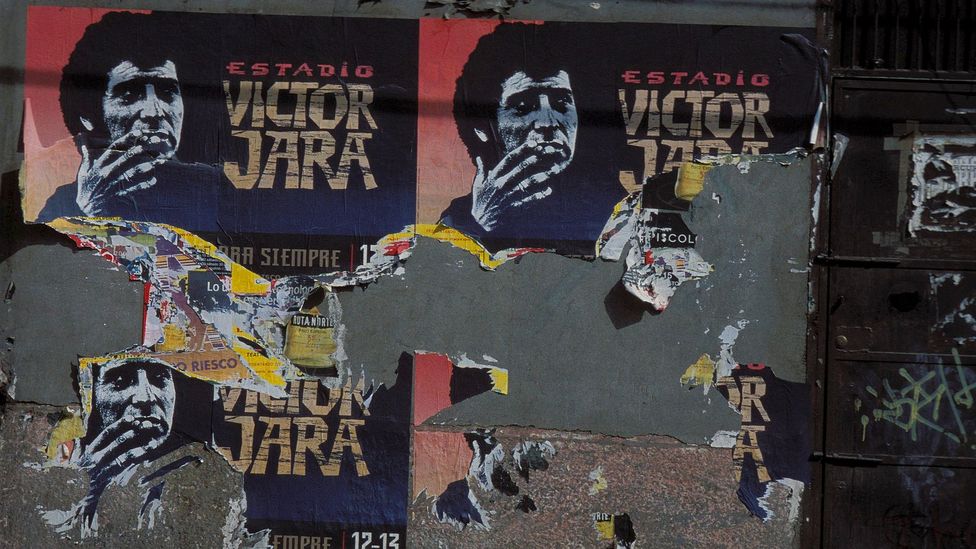

In Chile, Victor Jara remains an icon and his death an unforgettable episode in a national trauma. In 2003, 13 years after Pinochet left office, Estadio Chile was renamed Estadio Victor Jara. In 2009, following new investigations into his murder, Victor’s body was reburied in a public funeral attended by thousands of mourners. In 2016, former Chilean army officer Pedro Barrientos was found liable for Jara’s death in a Florida civil court. In 2018, eight more retired officers were convicted and jailed for their involvement. After 45 years, justice had finally arrived. “I am one of the lucky ones” 91-year-old Joan Jara said following the verdict. “So many people here in Chile, so many families, they still don’t know the destiny of their loved ones. That is the worst fate.”

Victor Jara remains an icon in Chile, and in 2003 its national stadium was named after him (Credit: Getty Images)

Unusually cruel and brutal though Jara’s plight was, Jones thinks it would be a mistake to think of it as unique. “To me, Victor’s story is a warning from history. Look at the images coming from Portland in America: people pulling protesters off the streets. These forces haven’t gone away. Power is always afraid of those who stand up and say ‘no, there’s another way’.”

Just as Bradfield discovered Jara through The Clash, he hopes that his album and podcast will introduce new listeners to this extraordinary character. “My gateway to Victor Jara was music, and then I kept hearing the echo time and time again,” he says. “I wanted to show that here’s an echo that doesn’t die.”

Even in Exile is released on 14 August. The first and second episodes of Inspired by Jara are out now.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.