For more than 100 years, activists have drawn attention to the depiction of female nudes in art. Is it time to look at them with fresh eyes, asks Lizzie Enfield.

A

At the time the Black Lives Matter campaign in the UK was drawing the national spotlight to the statues of slave traders, another activist was highlighting the way women are represented in civic statuary. “Just look at what you are being socialised to accept as normal…” says the activist’s placard, focusing on a monument outside the Trafford Centre in Manchester. It shows a seated man bathing his feet surrounded by a clutch of fawning semi-naked women. Another sign beside a statue in Iowa, US – of a bronze topless woman arching her back and holding her breasts as if to deliberately enhance her cleavage – reads: “Iowa as a mother figure offering nourishment to her children? Yeah.”

More like this:

– Gauguin’s beautiful and ‘exploitative’ portraits

– How black women were whitewashed by art

– Is the Renaissance nude religious or erotic?

The placard bearer is ArtActivistBarbie, a Barbie doll posed in front of artworks and monuments, and the playful alter ego of Sarah Williamson, a senior lecturer at the University of Huddersfield. Williamson began the project as way to engage students with feminist ideas, and in particular the way women are portrayed in art. “This way, I can lead people gently into those conversations,” Williamson tells BBC Culture. “It’s a form of feminist ventriloquism – my voice, being spoken through a third party with AAB [ArtActivistBarbie] is the equivalent of a ventriloquist’s dummy.”

ArtActivistBarbie poses with a toy tiger in a parody of the 1889 painting Circe by Wright Barker, showing a topless woman surrounded by lions (Credit: Sarah Williamson/Twitter)

In a Twitter post, ArtActivistBarbie imagines the commissioning of the 1889 painting Circe by Wright Barker, which shows a topless woman surrounded by lions. “‘I’d like a seductive young beauty, half undressed, confined and with some big game,’ said the patron”, the Twitter post reads. “‘How about Circe, say with 5 or 6 tigers?'” said the artist. ‘Everyone will admire your scholarly interest in Greek Mythology.'” With her tongue firmly in her cheek, ArtActivistBarbie asks if this is the depiction of a classical scene or thinly veiled Victorian porn.

The classics professor Mary Beard asked a similar question in her TV series Shock of the Nude, which aired earlier this year in the UK. The programme explored the many ways male artists have tried to justify the existence of naked women in their paintings: reclining nudes are depicted as innocently ‘caught’, half-bathing or somehow sleepily compromised in a state of undress.

So is what we are looking at art or pornography?

“That is a complicated question and anyone who thinks they know the answer should reflect a bit harder!” Professor Beard tells BBC Culture. “My line is that the boundary between art and pornography is always a treacherous one and the point about the past is that we have to see it both in its own terms and ours. We have to learn to look the past and its faults in the eye.”

A contentious issue

For more than 100 years, feminists have drawn attention to sexist attitudes that exist within the art world. In 1914, the suffragist Mary Richardson attacked Velazquez’s Rokeby Venus with an axe. The painting portrays Venus looking in the mirror, turned away from the viewer with her bottom at the centre of the canvas. Richardson claimed her protest was partly at the way men gaped at the painting, which hangs in London’s National Gallery.

In 1914 the suffragist Mary Richardson attacked Velazquez’s Rokeby Venus in protest at its portrayal of the female nude (Credit: Getty Images)

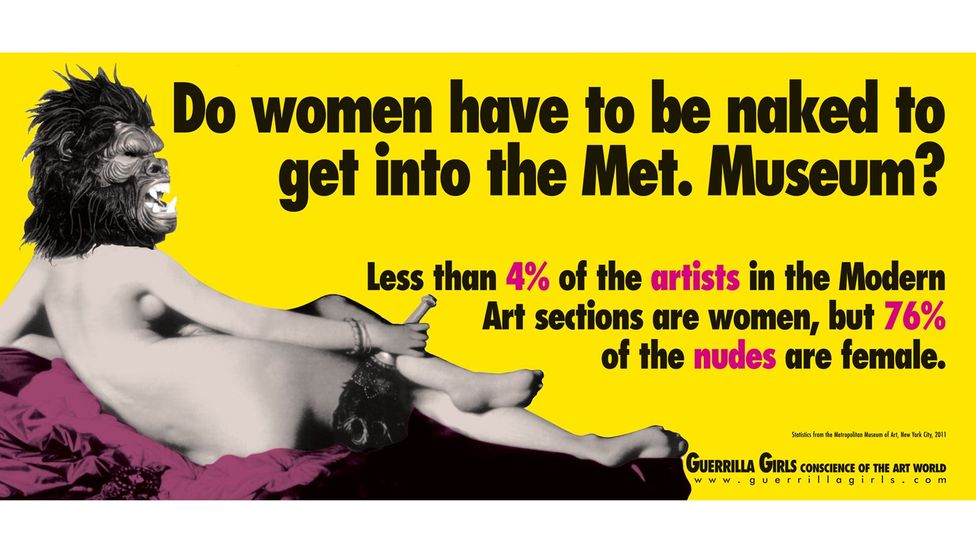

“Do women have to be naked to get into the Met Museum?” shouted one billboard poster put up by feminist art activists Guerrilla Girls in the 1980s. At the time it seemed they did – less than 4% of artists in the modern art section of the museum were by women, but 76% of the nudes were female. With smart, cutting messages delivered via large-scale billboard works, the Guerilla Girls sought to name and shame the art world for its unapologetic disregard for women and other minorities in art.

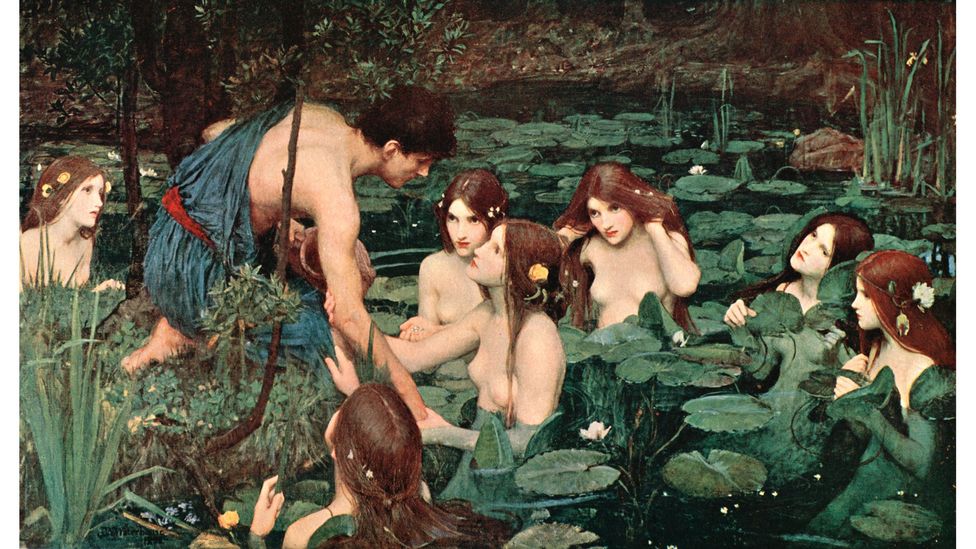

In 2018, British artist Sonia Boyce took a different approach when she staged a removal, in front of an audience, of Hylas and the Nymphs by John William Waterhouse from Manchester Art Gallery. The space on the wall, where the painting depicting a clutch of semi-naked young girls luring Hylas into a lily pond had hung, was left empty for a week. “My aim was to draw attention to – and question – the ways in which museums make decisions about what visitors see, in what context and with what labelling,” Boyce said after the move provoked a furious backlash with accusations of censorship, political correctness and feminist extremism. “Taking the picture down was about starting a discussion, not provoking a media storm.” It did both. The issue of art and pornography is a contentious one.

In the 1980s, feminist art activists Guerilla Girls famously asked ‘Do women have to be naked to get into the Met Museum?’ (Credit: Guerilla Girls)

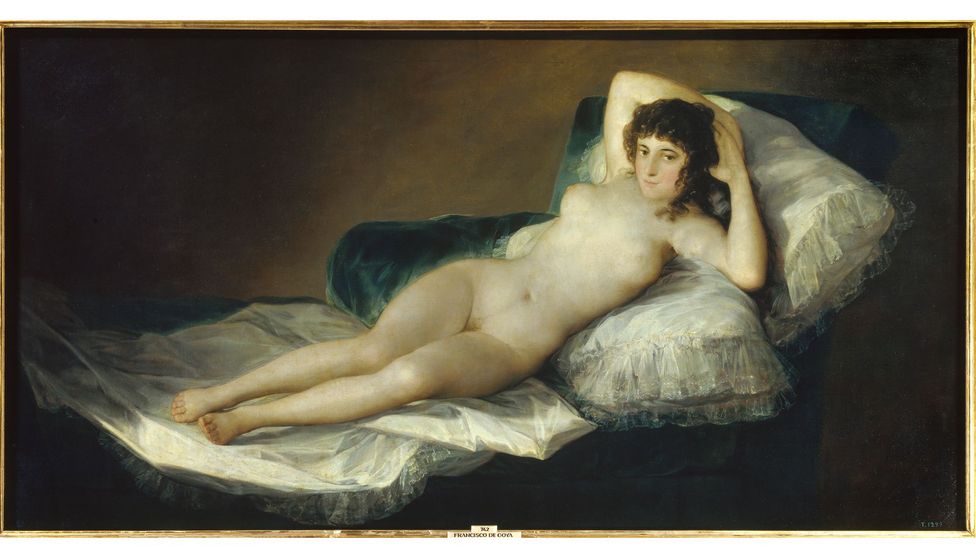

“The boundaries have always been blurred,” says Hans Maes, a lecturer in art history at Kent University who has written extensively on the subject. “It’s generally assumed that pornography has two key characteristics: it’s sexually explicit and its aim is to sexually arouse the viewer. Well, throughout history and across cultures you can find great works of art that share those very characteristics. Think of some of the mosaics in Pompeii, Kama Sutra sculptures or some of Gustav Klimt’s explicit drawings. If you want, compare Goya’s Naked Maja to a Playboy centrefold and tell me the line is not blurred.”

In 2014, performance artist Deborah de Robertis sought to make just this point by exposing herself in front of Gustave Courbet’s The Origin of the World painting in the Musee d’Orsay in Paris to reproduce the close-up image of a woman’s genitals. She was subsequently arrested for posing naked in front of Manet’s Olympia, also in the Musee d’Orsay. Her point was to raise the question: why is one representation of the human body defined as art and another as pornography?

Goya’s Naked Maja (above), Courbet’s The Origin of the World and Klimt’s explicit drawings are works that some historians and activists think ‘blur lines’ (Credit: Getty Images)

In the past, censorship of explicit images was often motivated by conservative and religious values and fears of moral corruption. By contrast, feminists who challenge objectifying sexual imagery want equal rights for women, and they fear the spread of objectifying images is detrimental to that cause. At the time of Boyce’s intervention in Manchester, a fourth wave of feminism was surging amid the wave of accusations against Harvey Weinstein and Jeffrey Epstein and others, and there was a surge of anxiety about how to deal with art made under different ethical conditions from our own.

You don’t have to look very far to find examples. Benvenuto Cellini insisted on using young virgins as models and ‘deflowering’ them once he had finished painting them. Eric Gill used his own daughters as models and sexually abused them. “We should perhaps distinguish between the context of appreciation and the context of creation,” Maes tells BBC Culture. “If we know that an artist abused women and his abusive attitudes are also manifest in the work, then that does affect the status of the work. The work itself will come to appear seedy and morally problematic, once you become aware.”

In 2018, the artist Sonia Boyce staged a removal of John William Waterhouse’s Hylas and the Nymphs from Manchester Art Gallery (Credit: Getty Images)

In the recent Jeffrey Epstein documentary on Netflix, one of the arresting police officers comments on the sheer volume of nudes on display in the sex offender’s mansion. In a gallery, similar nudes might be objects of admiration.

“Well it does make you think,” agrees Sarah Williamson. “There are many paintings in our public art galleries of young pubescent girls, which make for uncomfortable viewing. The Syrinx by Arthur Hacker on display in Manchester Art Gallery for example, shows a young girl, naked, looking vulnerable and scared and it makes me feel very uncomfortable to view it. But there’s a type of reverence to these institutions with their language of Old Masters and masterpieces which we absorb unconsciously and acceptingly.”

‘Naked’ or ‘nude’?

Life drawing from nude models is still the mainstay of a fine art education and the vast majority of models are women; yet in the ‘sanctity’ of the life-drawing room, these women are not naked but ‘nude’, and they don’t strip but ‘disrobe’.

“But of course, the male gaze exists in the life-drawing class,” says Mary Beard, who herself posed as part of her investigation in Shock of the Nude. “There are various ways culture tries to remove it and those linguistic devices are used to try to desexualise the encounter. But it’s there.”

“Posing virtually was something I had hoped to avoid,” model Fra Beecher wrote in a blog about life modelling online during lockdown, which illustrated her own awareness of the male gaze. “I never allow photographs to be taken of myself when I am modelling. I wondered if it would be possible to reconcile my feelings regarding nude photography with my fear of appearing nude online.” Another life model expressed a blunter concern: that away from the confines of the life-drawing room, participants were free to masturbate rather than draw.

Another of ArtActivistBarbie’s subjects is Manet’s Le Dejeuner sur l’Herbe, where a female nude is accompanied by two fully-clothed men (Credit: Getty Images)

Both women’s concerns show how fine the line between art and pornography is and how tricky trying to negotiate it is. Mary Beard’s claim in an interview that the nude is always in danger of being “soft porn for the elite” was met with abusive messages in the article comments and on Twitter. Like Boyce, she discovered that trying to start a discussion on the subject tends to inspire hostility rather than interest.

Which is why ArtActivistBarbie, subverting a plastic doll widely vilified by feminists for being a gender stereotype, was a stroke of genius on her creator’s part. “The issue is discussion and starting to view things differently,” says Sarah Williamson. “AAB provides a fun and playful way of doing this and, in doing so, trying to create a world in which there is more equality for women and where they are not just the subject of the male gaze.”

In one of ArtActivistBarbie’s most commented-on posts, she poses on the floor of a gallery in front of Manet’s Le Dejeuner sur l’herbe. In the first picture, Barbie is naked like the woman in the picture and her two male companions are fully clothed. But then the set-up is reversed and Barbie appears in her glad rags while the two men are naked.

It’s an interesting juxtaposition and one that certainly makes you think.

ArtActivistBarbie is on Twitter @barbiereports.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.