Miriam was only 21 when she met Nick. She was a photographer, fresh out of college, waiting tables. He was 16 years her senior and a local business owner who had worked in finance. He was charming and charismatic; he took her out on fancy dates and paid for everything. She quickly fell into his orbit.

It began with one credit card. At the time, it was the only one she had. Nick would max it out with $5,000 worth of business purchases and promptly pay it off the next day. Miriam, who asked me not to use their real names for fear of interfering with their ongoing divorce proceedings, discovered that this was boosting her credit score. Having grown up with a single dad in a low-income household, she trusted Nick’s know-how over her own. He readily encouraged the dynamic, telling her she didn’t understand finance. She opened up more credit cards for him under her name.

The trouble started three years in. Nick asked her to quit her job to help out with his business. She did. He told her to go to grad school and not worry about compounding her existing student debt. She did. He promised to take care of everything, and she believed him. Soon after, he stopped settling her credit card balances. Her score began to crater.

Still, Miriam stayed with him. They got married. They had three kids. Then one day, the FBI came to their house and arrested him. In federal court, the judge convicted him on nearly $250,000 of wire fraud. Miriam discovered the full extent of the tens of thousands of dollars in debt he’d racked up in her name. “The day that he went to prison, I had $250 cash, a house in foreclosure, a car up for repossession, three kids,” she says. “I went within a month from having a nanny and living in a nice house and everything to just really abject poverty.”

Miriam is a survivor of what’s known as “coerced debt,” a form of abuse usually perpetrated by an intimate partner or family member. While economic abuse is a long-standing problem, digital banking has made it easier to open accounts and take out loans in a victim’s name, says Carla Sanchez-Adams, an attorney at Texas RioGrande Legal Aid. In the era of automated credit-scoring algorithms, the repercussions can also be far more devastating.

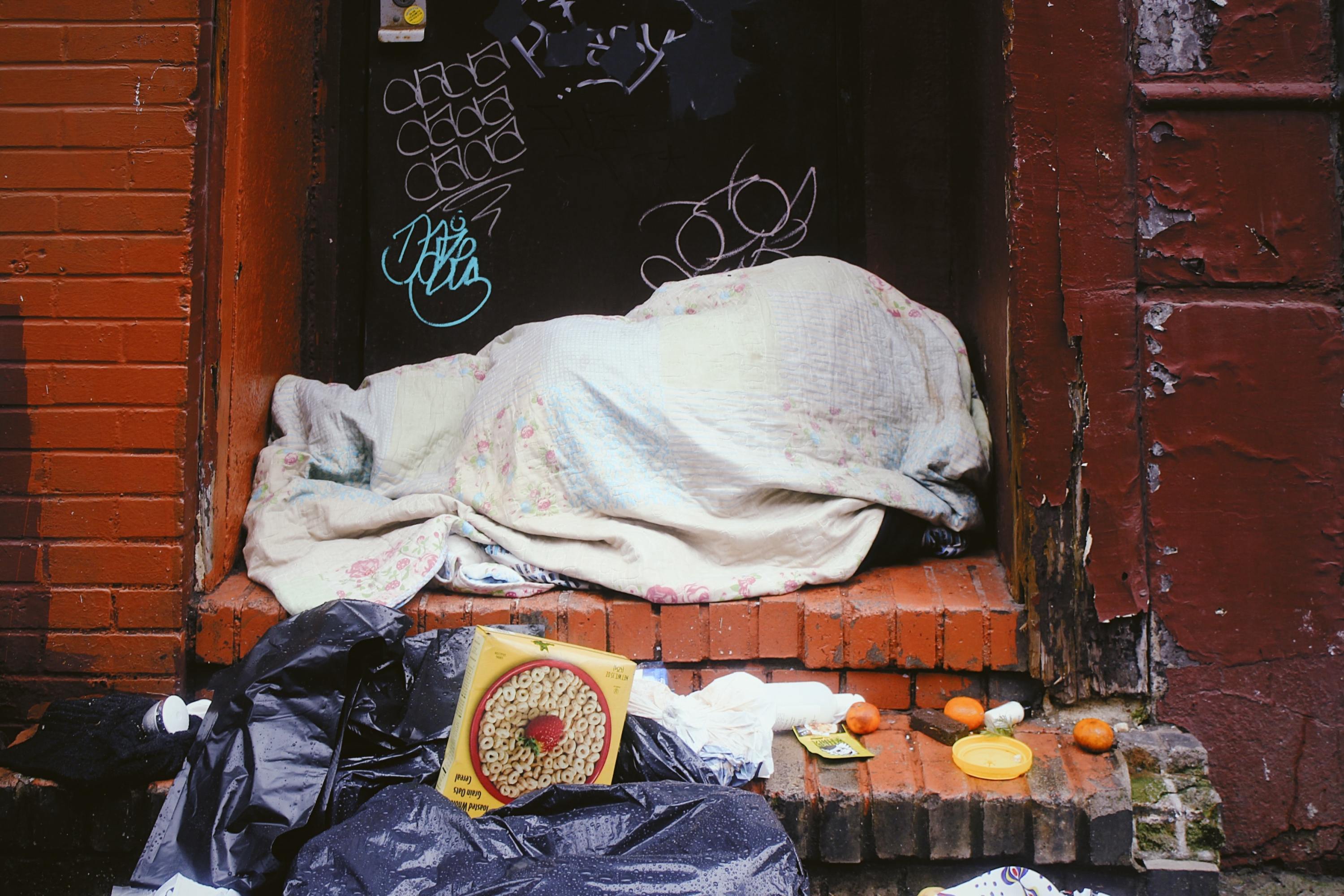

Credit scores have been used for decades to assess consumer creditworthiness, but their scope is far greater now that they are powered by algorithms: not only do they consider vastly more data, in both volume and type, but they increasingly affect whether you can buy a car, rent an apartment, or get a full-time job. Their comprehensive influence means that if your score is ruined, it can be nearly impossible to recover. Worse, the algorithms are owned by private companies that don’t divulge how they come to their decisions. Victims can be sent in a downward spiral that sometimes ends in homelessness or a return to their abuser.

Credit-scoring algorithms are not the only ones that affect people’s economic well-being and access to basic services. Algorithms now decide which children enter foster care, which patients receive medical care, which families get access to stable housing. Those of us with means can pass our lives unaware of any of this. But for low-income individuals, the rapid growth and adoption of automated decision-making systems has created a hidden web of interlocking traps.

Fortunately, a growing group of civil lawyers are beginning to organize around this issue. Borrowing a playbook from the criminal defense world’s pushback against risk-assessment algorithms, they’re seeking to educate themselves on these systems, build a community, and develop litigation strategies. “Basically every civil lawyer is starting to deal with this stuff, because all of our clients are in some way or another being touched by these systems,” says Michele Gilman, a clinical law professor at the University of Baltimore. “We need to wake up, get training. If we want to be really good holistic lawyers, we need to be aware of that.”

“Am I going to cross-examine an algorithm?”

Gilman has been practicing law in Baltimore for 20 years. In her work as a civil lawyer and a poverty lawyer, her cases have always come down to the same things: representing people who’ve lost access to basic needs, like housing, food, education, work, or health care. Sometimes that means facing off with a government agency. Other times it’s with a credit reporting agency, or a landlord. Increasingly, the fight over a client’s eligibility now involves some kind of algorithm.

“This is happening across the board to our clients,” she says. “They’re enmeshed in so many different algorithms that are barring them from basic services. And the clients may not be aware of that, because a lot of these systems are invisible.”

JON TYSON / UNSPLASH

She doesn’t remember exactly when she realized that some eligibility decisions were being made by algorithms. But when that transition first started happening, it was rarely obvious. Once, she was representing an elderly, disabled client who had inexplicably been cut off from her Medicaid-funded home health-care assistance. “We couldn’t find out why,” Gilman remembers. “She was getting sicker, and normally if you get sicker, you get more hours, not less.”

Not until they were standing in the courtroom in the middle of a hearing did the witness representing the state reveal that the government had just adopted a new algorithm. The witness, a nurse, couldn’t explain anything about it. “Of course not–they bought it off the shelf,” Gilman says. “She’s a nurse, not a computer scientist. She couldn’t answer what factors go into it. How is it weighted? What are the outcomes that you’re looking for? So there I am with my student attorney, who’s in my clinic with me, and it’s like, ‘Oh, am I going to cross-examine an algorithm?'”

For Kevin De Liban, an attorney at Legal Aid of Arkansas, the change was equally insidious. In 2014, his state also instituted a new system for distributing Medicaid-funded in-home assistance, cutting off a whole host of people who had previously been eligible. At the time, he and his colleagues couldn’t identify the root problem. They only knew that something was different. “We could recognize that there was a change in assessment systems from a 20-question paper questionnaire to a 283-question electronic questionnaire,” he says.

It was two years later, when an error in the algorithm once again brought it under legal scrutiny, that De Liban finally got to the bottom of the issue. He realized that nurses were telling patients, “Well, the computer did it–it’s not me.” “That’s what tipped us off,” he says. “If I had known what I knew in 2016, I would have probably done a better job advocating in 2014,” he adds.

“One person walks through so many systems on a day-to-day basis”

Gilman has since grown a lot more savvy. From her vantage point representing clients with a range of issues, she’s observed the rise and collision of two algorithmic webs. The first consists of credit-reporting algorithms, like the ones that snared Miriam, which affect access to private goods and services like cars, homes, and employment. The second encompasses algorithms adopted by government agencies, which affect access to public benefits like health care, unemployment, and child support services.

On the credit-reporting side, the growth of algorithms has been driven by the proliferation of data, which is easier than ever to collect and share. Credit reports aren’t new, but these days their footprint is far more expansive. Consumer reporting agencies, including credit bureaus, tenant screening companies, or check verification services, amass this information from a wide range of sources: public records, social media, web browsing, banking activity, app usage, and more. The algorithms then assign people “worthiness” scores, which figure heavily into background checks performed by lenders, employers, landlords, even schools.

Government agencies, on the other hand, are driven to adopt algorithms when they want to modernize their systems. The push to adopt web-based apps and digital tools began in the early 2000s and has continued with a move toward more data-driven automated systems and AI. There are good reasons to seek these changes. During the pandemic, many unemployment benefit systems struggled to handle the massive volume of new requests, leading to significant delays. Modernizing these legacy systems promises faster and more reliable results.

But the software procurement process is rarely transparent, and thus lacks accountability. Public agencies often buy automated decision-making tools directly from private vendors. The result is that when systems go awry, the individuals affected—-and their lawyers–are left in the dark. “They don’t advertise it anywhere,” says Julia Simon-Mishel, an attorney at Philadelphia Legal Assistance. “It’s often not written in any sort of policy guides or policy manuals. We’re at a disadvantage.”

The lack of public vetting also makes the systems more prone to error. One of the most egregious malfunctions happened in Michigan in 2013. After a big effort to automate the state’s unemployment benefits system, the algorithm incorrectly flagged over 34,000 people for fraud. “It caused a massive loss of benefits,” Simon-Mishel says. “There were bankruptcies; there were unfortunately suicides. It was a whole mess.”

SCOTT HEINS/GETTY IMAGES

Low-income individuals bear the brunt of the shift toward algorithms. They are the people most vulnerable to temporary economic hardships that get codified into consumer reports, and the ones who need and seek public benefits. Over the years, Gilman has seen more and more cases where clients risk entering a vicious cycle. “One person walks through so many systems on a day-to-day basis,” she says. “I mean, we all do. But the consequences of it are much more harsh for poor people and minorities.”

She brings up a current case in her clinic as an example. A family member lost work because of the pandemic and was denied unemployment benefits because of an automated system failure. The family then fell behind on rent payments, which led their landlord to sue them for eviction. While the eviction won’t be legal because of the CDC’s moratorium, the lawsuit will still be logged in public records. Those records could then feed into tenant-screening algorithms, which could make it harder for the family to find stable housing in the future. Their failure to pay rent and utilities could also be a ding on their credit score, which once again has repercussions. “If they are trying to set up cell-phone service or take out a loan or buy a car or apply for a job, it just has these cascading ripple effects,” Gilman says.

“Every case is going to turn into an algorithm case”

In September, Gilman, who is currently a faculty fellow at the Data and Society research institute, released a report documenting all the various algorithms that poverty lawyers might encounter. Called Poverty Lawgorithms, it’s meant to be a guide for her colleagues in the field. Divided into specific practice areas like consumer law, family law, housing, and public benefits, it explains how to deal with issues raised by algorithms and other data-driven technologies within the scope of existing laws.

If a client is denied an apartment because of a poor credit score, for example, the report recommends that a lawyer first check whether the data being fed into the scoring system is accurate. Under the Fair Credit Reporting Act, reporting agencies are required to ensure the validity of their information, but this doesn’t always happen. Disputing any faulty claims could help restore the client’s credit and, thus, access to housing. The report acknowledges, however, that existing laws can only go so far. There are still regulatory gaps to fill, Gilman says.

Gilman hopes the report will be a wake-up call. Many of her colleagues still don’t realize any of this is going on, and they aren’t able to ask the right questions to uncover the algorithms. Those who are aware of the problem are scattered around the US, learning about, navigating, and fighting these systems in isolation. She sees an opportunity to connect them and create a broader community of people who can help one another. “We all need more training, more knowledge–not just in the law, but in these systems,” she says. “Ultimately it’s like every case is going to turn into an algorithm case.”