Cameron Laux picks out reading that can help us focus our attention – and glimpse the sublime – including a quarantine list of reads from Zadie Smith.

T

There are many skeletons in our literary closets. Novels like Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace or Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick often put people off because of their length, and may linger on our reading lists for years, or decades. Others, like Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time or James Joyce’s Ulysses, have become a byword for daunting, modernist, experimental writing that is unintelligible without resorting to scholarly notes – pushing the novel form to its limit. Especially these days, who is going to question your desire to sit and binge on crime thrillers, if that’s what you want? And yet, what if we treat the current crisis as an opportunity to put aside our aversion to ‘the challenging read’? Is now the time for us to pay some attention to other things, including attention itself?

More like this:

– The best books of the year so far

– A 13th-Century poet’s lessons for today

– Short stories for every taste and mood

In her 2014 book Dept. of Speculation, Jenny Offill recounts an anecdote: “The Zen master Ikkyu was once asked to write a distillation of the highest wisdom. He wrote only one word: Attention. The visitor was displeased. ‘Is that all?’ So Ikkyu obliged him. Two words now: Attention. Attention.” Offill writes magnificent, terse, oracular books which enact the idea that worlds can be opened up by paying close heed to things. I propose that we consider the possibility of recalibrating our minds and focusing on demanding writers. Two key thinkers on this subject are Jenny Odell – whose revolutionary book How To Do Nothing encourages us to wake up to, and resist, all the petty 21st-Century demands on our attention – and Zadie Smith, who is a wonderful novelist, but also a patient and intelligent critic (she has even managed to write a collection of essays during lockdown, due to be published on 28 July). Odell encourages us to make space in which to think. Smith encourages us to use it.

By rethinking our ideas of contemplation, and shifting our attention, we can tackle more demanding books (Credit: Getty Images/Javier Hirschfeld)

Odell urges us to approach with strong scepticism the ‘attention economy’ that is manifested in our smartphones and is designed to attack the very ideas of contemplation and of personal space. Smith is an indefatigable contemplater. Her range of reference is huge, and she inspires me to broaden my own. For example, she turned my view of the famously daunting writer David Foster Wallace on its head. Not long after the US author committed suicide in 2008, Smith wrote The Difficult Gifts of David Foster Wallace (which is in her collection Changing My Mind). It helps us to reassess DFW, often regarded as an obscure, uncompromising, avant-garde geek who wrote impenetrable tracts. Smith says, “To appreciate Wallace you need to really read him – and then you need to reread him. For this reason – among many others – he was my favourite living writer.”

Wallace, who committed suicide at the age of 46, once said that good writing should help readers to “become less alone inside” (Credit: Getty Images)

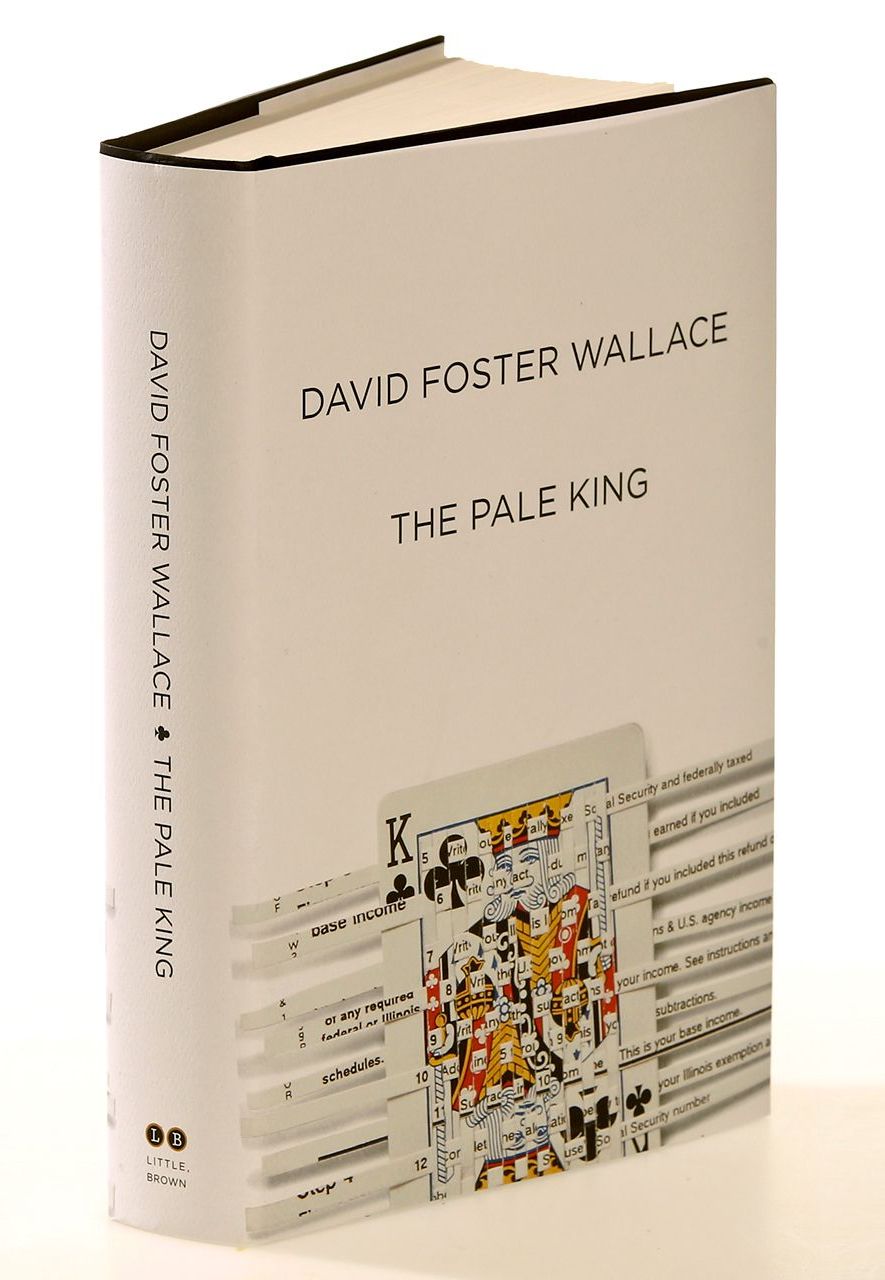

Smith is captivated by the short stories in DFW’s Brief Interviews with Hideous Men (1999). I never ‘got’ DFW until I started reading The Pale King (2011), the book he was working on when he died, and which was published posthumously. Then I had an epiphany. This is a book about the heroism of late capitalist boredom, an exquisite appreciation of dullness. It is set in, and steeped in the culture of, an Internal Revenue Service centre. The structure of the book is polyphonic and fragmentary: I suggest you try chapter 19, in which people trapped on an elevator have a civics discussion, or the formally mind-blowing chapter 25, in which nothing happens but the turning of pages, and yet there are ghosts, and everything happens. At this moment I can’t think of a better example than The Pale King of what the contemporary novel can do when it throws caution to the wind.

Smith’s 2008 essay Two Paths for the Novel (reproduced in her collection of essays Changing My Mind) dented my view of realism in fiction. In it, Smith suggested that a certain predictable “lyrical realism” had become the acceptable face of contemporary fiction (she takes Joseph O’Neill’s Netherland, 2008, as an example) at the expense of a more stringent metafictional tradition (eg Virginia Woolf, Joyce, and Samuel Beckett), which poses difficult questions about reality and human psychology, and the ability of words to describe them (she uses Tom McCarthy’s Remainder, 2005, as an example).

Often viewed as impenetrable, Joyce’s Ulysses is nevertheless so admired that it’s part of Dublin’s tourist trail (Credit: Getty Images)

Smith says that lyrical, realist novels offer “the nostalgic pleasure of returning to a narrative time when symbols and mottoes were full of meaning and novels weren’t neurotic, but could aim themselves simply and purely at transcendent feeling”. In other words, the author projects themselves poetically, the more poetically the better, on to their subject, and mistakes the procedure for meaning. In O’Neill’s book, which is set in post-9/11 New York, the destruction of the Twin Towers portends the collapse of a marriage, among other things. Books like this don’t always require our full attention. Of course there is also much to be said for permitting your mind to surf on a book, as there is for letting your mind move over any art form and pick up sparks from it.

Rethinking ‘reality’

The approach of a McCarthy novel, in contrast, is more dicey. A writer and artist, steeped in 20th-Century French thought, he issues ironic, artistic edicts, such as calling for “all cults of authenticity to be abandoned”. (Don’t worry, McCarthy has a sense of humour.) Book reviews have called him a latter-day Franz Kafka and a new Thomas Pynchon. I always think: okay, but what was wrong with the old ones?

In Two Paths, Smith says that McCarthy’s project is “to rid the self of its sacredness” – a campaign that so far extends over four novels. She calls Remainder “one of the great English novels of the past ten years”. It is written with a sparse elegance that makes few traditional concessions to the reader. The book’s main character, who isn’t named, suffers a blow to the head in an unspecified accident, and after seeing a crack in the plaster of a bathroom wall, begins to obsess about whether reality is real. He uses his large insurance settlement in increasingly elaborate attempts to stage an authentic reality. We never have a sense of who he is because he doesn’t know who he is, and never finds out.

In a 2014 article called Writing Machines: On Realism and the Real, McCarthy protests that “Time and again we hear about a new desire for the real, about a realism which is realistic set against an avant-garde which isn’t”. He goes on to argue that a writer (artist, etc) can never know the real; that what they imagine to be the real is always inauthentic; and that the real can only assert itself as “rupture” of our expectations. It is in the nature of art to crack and fragment; acknowledging the unreliability of our perception might be a good thing.

David Cronenberg adapted JG Ballard’s novel Crash into a film in 1996 (Credit: Getty Images)

Both Smith and McCarthy are drawn to JG Ballard’s novel Crash (1973), an intriguingly warped book about the intersection of sex, death, technology, psychology and loss of meaning, that provoked the establishment of the time to froth at the mouth about pornography. It is now seen as a classic. In her introduction to the 2009 re-issue, Smith talks about how radically the book reverses the relationship between man and technology: instead of the former using the latter, the latter uses and defines (and empties) the former. For all that, Crash is an oddly humane book. It is definitely not comfort reading.

And its characters are a puzzle; we can’t ever entirely know them. This is a characteristic of what are loosely called the postmodern novelists (in the sense that postmodern means being self-conscious about the business of being an author). Some people find this lack of narrative bearings frustrating, but I find it inspiring. I am happy to get lost in these books and work for my glimpses of the sublime. If you’re patient, they always deliver. Vladimir Nabokov is one of the fathers of playful, humane metafiction. Everyone talks about Lolita, but in many ways he is at his best in Pnin – which Smith also cites as one of her favourite books. The gradual sketching in of the main character, Timofey Pnin, is a confusing delight.

Harold Bloom, one of the greatest of literary critics, who died last year, talks about a canon of the “American sublime” that encompasses the great postmodern writers: Cormac McCarthy, Don DeLillo, Thomas Pynchon, Philip Roth. Bloom especially settles on Pynchon, grand master of the glorious, writerly tailspin, the first author sleepy readers say they want to avoid. There will be no surfing on Pynchon. Either you control your breathing and give his sentences your full attention, or you put the book down, pick up some genre fiction (my poison is epic fantasy at the moment), and come back to him another day. Bloom loved all of Pynchon, but he singled out the novella The Crying of Lot 49 as an important artefact, and that may be the best place to start.

Of course, there are those who disagree. In a now-famous essay, the high-profile critic James Wood sets out to damn the likes of Pynchon, DeLillo, DFW, and Salman Rushdie. He implies these writers, with their vertiginous lack of artistic boundaries, are dysfunctional and need to seek treatment. (This move: I’m not crazy, you’re the one who’s crazy!) He says: “An excess of storytelling has become the contemporary way of shrouding, in majesty, a lack; it is the Sun King principle. That lack is the human.”

A second version of Wood’s essay, published in The Guardian, blames DeLillo for everything: “Lately, any young American writer of any ambition has been imitating DeLillo”; his technical virtuosity in extremis, his fiddling while Rome burns. The Rome in question is the US after 9/11. Yet no writer has anatomised the US since World War Two more convincingly and devastatingly than DeLillo: its paranoia, violence, egotism, consumerism.

Now 83, DeLillo has been described by The Guardian as “America’s weathervane, its Geiger counter, mapping the landscape in pin-sharp prose” (Credit: Getty Images)

One way into DeLillo’s work is via his 1997 magnum opus, Underworld: parts of it previously appeared as short stories. Instead of trying to swallow the whole thing, like a snake eating a buffalo, it is possible to sample the book instead. The Prologue, about baseball, is one of the great bravura performances of modern prose. But Part One, Long Tall Sally, is more accessible, and more likely to pull you in. The sustained pitch of his imagination, of poetry, throughout the book is just astonishing. In a love letter to DeLillo about Underworld, DFW wrote that it was a book “in which absolutely nothing is skimped or shirked or tossed off or played for the easy laugh, and where… you’ve taken some truly ballsy personal risks and exposed parts of yourself and hit a level of emotion you’ve never even tried for elsewhere” (his praise for the novel continued for two pages).

One of the best recent examples of this kind of risk-taking is in a novel that Smith herself wrote. In 2012 she published NW, perhaps the most experimental of her books so far and, it could be argued, one of the defining novels of its time. NW is also polyphonic – it shifts through multiple points of view in multiple authorial styles. The book is a collaboration between Charles Dickens and Woolf, with Smith providing a marvelous ear for dialogue. It is a complicated combination of serious and funny, what Smith calls “laughter in the dark”, quoting Nabokov. (She talks about her reference points in a rejoinder to Wood that comes from the heart.) NW gently unfolds a partial picture of the lives of its characters. The effect is devastating. It is a ‘challenging read’, a subtle and beautiful book, that is worth picking up – even if it demands your full attention.

In her 2007 essay Fail Better, Smith argued that, in reading, “both the writer and the reader must undergo an ethical expansion – allow me to call it an expansion of the heart”

This is increasingly a stumbling block for many of these more demanding books. In the digital era, fragmentation has become a way of life. The attention economy, aided by our smartphones, is geared to destroy mental focus. There are ways we can opt out, of course. Odell warns of the “context collapse” fostered by social media, and enjoins us to turn away and open up “contemplative space”. She quotes the composer John Cage: “If something is boring after two minutes, try it for four. If still boring, then eight. Then sixteen. Then thirty-two. Eventually one discovers that it is not boring at all.”

Finding a focus

Odell’s How to Do Nothing is a great, radical book. Who would have thought that sitting in a rose garden and listening to the birds, as Odell talks about doing, could become such a political act? One of Cage’s most famous pieces, 4’33”, consists of a pianist playing nothing: it dares the audience to sit still and listen to the texture of collective life: coughing, farting, snoring, fidgeting, whatever. Phones going off. Odell says: “Unless we are vigilant, the current design of much of our technology will block us every step of the way, deliberately creating false targets for self-reflection, curiosity, and a desire to belong to a community.”

Being aware of the quality of one’s attention, and regaining control of it, are good first steps in approaching challenging fiction. It is also a good idea not to bite off more than you can chew. One reader got through Roberto Bolano’s hefty masterpiece 2666 by reading a few pages a day over the course of months. As with many of the experimentalists, parts of that book seem designed to test and break one’s patience, and yet the reward for opening your mind is a glimpse of some kind of sublime.

I asked Smith for her retrospective thoughts on Two Paths. She said “I wish I hadn’t used Joseph [O’Neill] as a straw man”. She called the essay “a provocation which, like provocations, has its limitations and excitements”. She also said this: “I don’t think in those terms any more. Even as you list the supposed forms of the ‘avant-garde’, the excitement drains out of me and I’m left only with ‘genres’, fixed modes etc. There is no fixed mode for unusual or interesting writing – perhaps the very definition of fresh writing is that it is sui generis [one of a kind]. With that in mind, so far in quarantine I’ve found these books very interestingly shaped: Humiliation by Paulina Flores, Stick out your Tongue by Ma Jian, Annie John by Jamaica Kincaid, New Waves by Kevin Nguyen, Endgame by Beckett, most of the stories in the anthologies Sudden Fiction and Sudden Fiction International, Catholics by Brian Moore, The Collected Grace Paley, the stories of Tillie Olsen, and Ma’am Darling: 99 Glimpses of Princess Margaret by Craig Brown. I am aware that… many of [these people] would not think of themselves as ‘experimental’. But in the structure of all of them, there’s something curiously shaped and unexpected and, to me, beautiful.”

Love books? Join BBC Culture Book Club on Facebook, a community for literature fanatics all over the world.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.