She gives little away about her private life, and touts a cartoonish public image: how did Dolly Parton become one of the world’s most-loved celebrities? Dorian Lynskey explores the singer’s appeal.

L

Last month, it was revealed that Dolly Parton had donated $1m (GBP744,000) to Moderna’s successful effort to develop a vaccine for Covid-19. The news inspired a joke (“It’s 9-to-5 per cent effective”), a fond YouTube parody (Vaccine, to the tune of Jolene), and yet another outpouring of love for a woman who inspires as much affection as any celebrity on Earth.

More like this:

– The instrument that ‘aided espionage’

– The album that defined an era

– Pop’s most underestimated icon

I witnessed the Dolly effect first-hand at Glastonbury in 2014, when she drew one of the biggest crowds in the festival’s history, an achievement made all the more remarkable by the fact that only two of the songs she recorded – Jolene and the Kenny Rogers duet Islands in the Stream – have ever made the UK Top 40. Throw in the floor-filling 9 to 5 and the showstopping I Will Always Love You, and she still has just four undeniably famous songs in her vast catalogue: far fewer than Kylie Minogue, Barry Gibb or other artists to have played the Sunday afternoon legend slot in the past decade. Her between-song patter, polished to a high shine, was the primary source of delight. Festival-goers enjoyed the music but they loved the person even more.

Parton attracted a crowd of more than 180,000 when she headlined Glastonbury in 2014 (Credit: Getty Images)

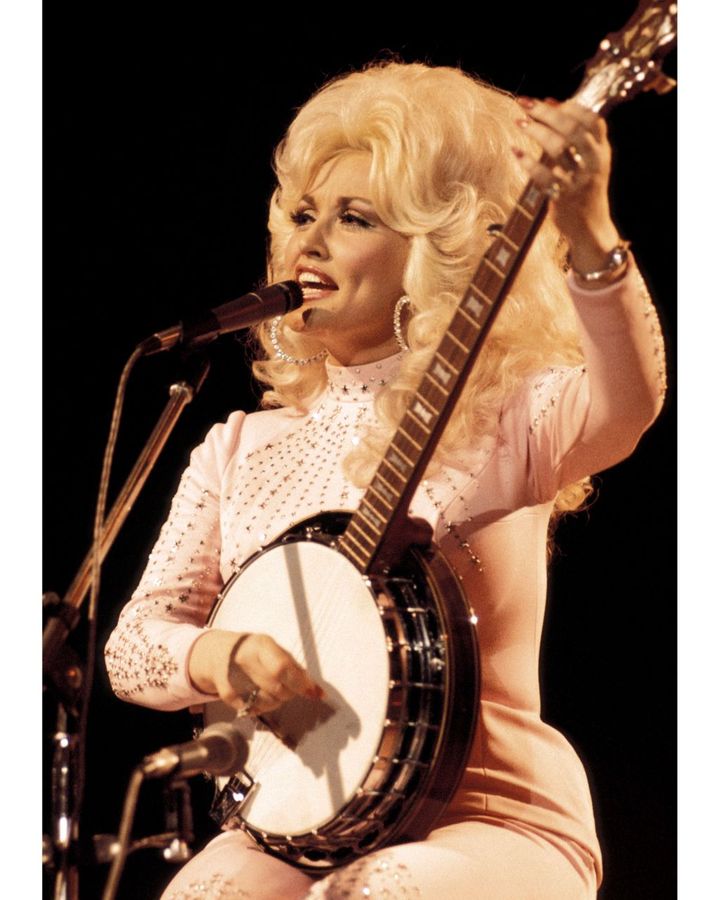

Parton’s fame used to have two distinct lanes. One was musical. As a writer and performer, she sits at country music’s top table with Hank Williams and Johnny Cash. She can play around 20 instruments, including the fiddle, dulcimer, mandolin and pan-flute. She has written, by her estimation, around 3000 songs, 175 of which are featured in a new book, Songteller: My Life in Lyrics. In the early 1970s she was on such a roll that a single session in 1973 yielded both Jolene and I Will Always Love You. “At the end of the day, I hope that I will be remembered as a good songwriter,” she writes in Songteller. “The songs are my legacy.”

The other Dolly, the one I grew up with, was a jovial, self-deprecating talk-show regular and spoofable symbol of US excess. One example of her pop-culture ubiquity is the 1981 Two Ronnies sketch in which Ronnie Barker donned a platinum-blonde wig and fake bosom to play “Polly Parton”. Jokes about Parton’s chest, many of which she made herself, became such a trope in British culture that when scientists cloned a sheep from a mammary gland cell in 1996, they called it Dolly. No wonder her songwriting chops were eclipsed.

In recent years, however, the two lanes have converged, and ascended to a higher plane of celebrity. Fuelled by her Glastonbury triumph, her 44th album, 2014’s Blue Smoke, became her most successful ever in the UK, while Netflix recently followed a drama series based on her songs, Dolly Parton’s Heartstrings, with a loving documentary, Here I Am, and a seasonal special, Dolly Parton’s Christmas on the Square. Last year, the hit nine-part podcast Dolly Parton’s America was predicated on the idea that she was a uniquely unifying figure in a divided nation. Even now that the discourse around music is hotly politicised, this 74-year-old red-state white woman has largely escaped being labelled “problematic”. She is worshipped by different sectors of her fanbase as a pioneering feminist heroine, a $500m (GBP371m) business phenomenon, an LGBTQ ally, a patriotic icon and a cultural ambassador for the working-class South.

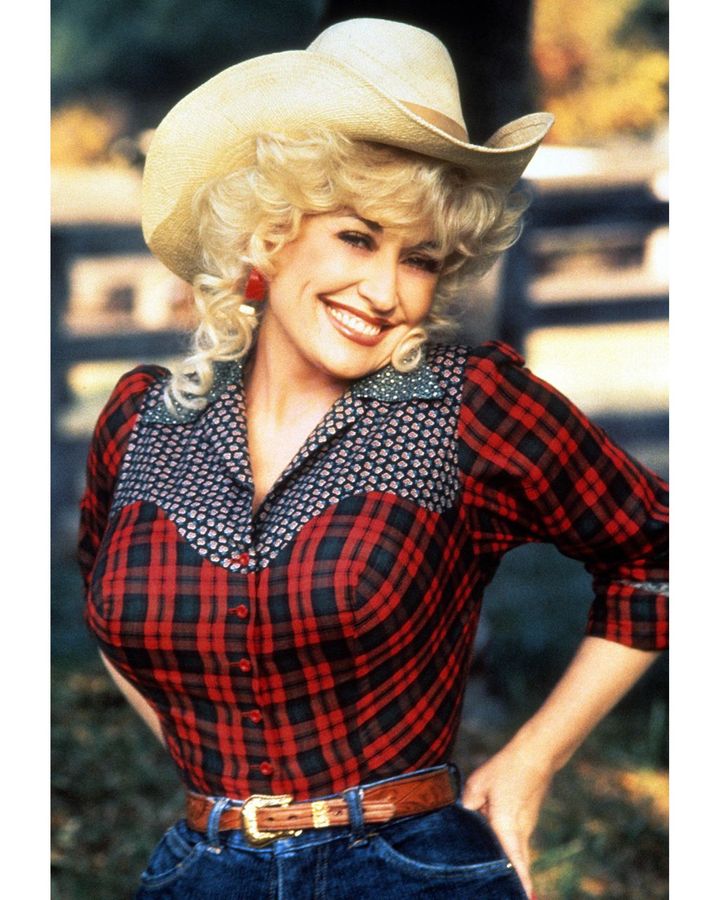

Parton combines country roots with being a pop culture icon (Credit: Alamy)

It helps that Parton is a black-belt interviewee, fully aware of her kitsch value, using humorous “Dollyisms” to sidestep anything that smells remotely of controversy and keep most of her private life and opinions under wraps. She is a master of distraction who wears her cartoonish public image like a suit of armour. “She gives away very little,” says her 9 to 5 co-star Lily Tomlin in Here I Am. “There’s a mystery about her.” Parton herself says: “People feel like they know me.” Both claims are true. Her Q Score, which measures the appeal of celebrity brands, is one of the highest in the world, with one of the lowest negative ratings. Not everybody loves Parton but very few people hate her. “I enjoy being loved,” she told the Guardian last year. How has Dolly Parton become the world’s sweetheart?

Parton’s origin story is the stuff of country songs, including some of her own, such as Coat of Many Colors and My Tennessee Mountain Home. Born in 1946, she grew up “dirt poor” in a one-room cabin on the banks of Tennessee’s Little Pigeon River with six brothers and five sisters. As a kid, she used to imagine that the chickens in the yard were her fans. She became a child star on local radio and TV, recording her first single at 13 and moving to Nashville the day after she graduated from high school. There she wrote several hits for other artists while still in her teens, before scoring her first solo hit in 1966 with Dumb Blonde. Right from the start, she was neutering criticism by owning it.

Ballads of woe

Songteller may surprise some casual fans with the bleakness of her early output. Starting with Hello, I’m Dolly in 1967, Parton’s first few albums specialised in what she calls “sad ass songs”: empathetic stories about horribly mistreated working-class women spiced with the bloody melodrama of the Appalachian folk ballads that had soundtracked her childhood. Subjects included suicide, miscarriage, alcoholism, drug addiction, homelessness, incarceration, murder, arson and potential incest. Although Parton herself has been married to Carl Dean since 1966, she expressed the pain of invisible women in a voice that rang pure and true. In the heyday of feminist country songs by women who didn’t call themselves feminists – Loretta Lynn, Tammy Wynette, Jeannie C Riley – she sang, in 1968’s Just Because I’m a Woman, “My mistakes are no worse than yours/ Just because I’m a woman.”

Parton took on a more glamorous image and more commercial material in the mid-1970s (Credit: Getty Images)

Parton really hit her songwriting stride in the mid-1970s, when her controlling mentor Porter Wagoner, a Nashville singer and impresario 19 years her senior with whom she sang as part of a duo, encouraged her to develop a more glamorous image and more commercial material. Jolene was a radical twist on the “cheating” genre, making the narrator desperate and helpless rather than vengeful, and entranced by the woman who threatens to ruin her life. It has since been covered by hundreds of artists, including the White Stripes and Miley Cyrus (Parton’s god-daughter), and was one of Nelson Mandela’s favourite songs. I Will Always Love You turned her split from Wagoner into a timeless break-up song, later made famous by Whitney Houston. The Bargain Store is an expertly extended metaphor about a woman whose life is piled high with broken dreams, painful memories and things in need of mending.

Parton was enough of a draw to headline the annual country festival at Wembley Arena in 1976 but the following year she transformed herself into a pop superstar with her first US platinum album, Here You Come Again. This crossover phase rolled on into the 1980s with her starring role and Oscar-nominated title song in the workplace satire 9 to 5 and Islands in the Stream. Like most of her pop hits, that wasn’t one of her compositions – her celebrity was overtaking her songwriting.

Parton stayed close to her 9 to 5 co-stars Lily Tomlin and Jane Fonda; the film was later made into a musical (Credit: Alamy)

“People thought I had sold out,” she told Rolling Stone in 1980. But those pop albums “got me where I wanted to be”. The journalist agreed: “If ever somebody figured out the American dream and made it work, it’s Dolly Parton.” That’s when she hit the talk-show circuit with a vengeance, responding to depressingly predictable jokes about her breasts by cracking better ones: she once quipped that when she burned her bra, it took the fire department three days to extinguish the flames. In retrospect, the tittering misogyny is appalling but Parton shrewdly decided that if she was going to be a punchline, then she was going to write it herself.

Even before the hits dried up in the 90s, Parton was turning herself into a heavyweight brand, opening the Dollywood theme park in Pigeon Forge, Tennessee in 1986. She had another memorable movie role in Steel Magnolias while, behind the scenes, her company Sandollar Productions was responsible for Buffy the Vampire Slayer. She also became a beloved philanthropist, funding scholarships, wildlife charities, hospitals and a literacy program that has given away more than 100 million books to children. After a back-to-her-roots bluegrass phase, Parton made a successful effort to revive her sales, starting in 2008 with the self-referential Backwoods Barbie: “I’m just a backwoods Barbie in a push-up bra and heels/ I might look artificial but where it counts, I’m real.” It’s a good line but to younger fans, the fact that authentic talent can coexist with presentational artifice doesn’t need spelling out like it did in the days of second-wave feminism. At 74, her reputation is practically bulletproof.

Parton combines a love of glamour with an ability to skewer herself; she has said “I look fake, but my world is real to me” (Credit: Alamy)

You can learn a lot about Parton from how she has navigated the Trump era. These past four years, celebrities have found it hard to duck the question, “Which side are you on?” Taylor Swift, like Parton, has a typical Nashville aversion to controversy but she was labelled everything from a coward to a closet white supremacist for her neutral stance until she finally came out as a Democrat in 2018. Parton, however, remains publicly apolitical at a time when it would seem impossible to be apolitical. Even when her 9 to 5 co-stars Jane Fonda and Lily Tomlin were savaging Trump right next to her on the stage at the 2017 Emmy Awards, Parton changed the subject with a trusty boob joke. When the topic came up on Dolly Parton’s America, she flatly shut it down: “I don’t do politics. I have too many fans on both sides of the fence.”

The easy explanation is that she puts business before principle, but for Parton those two instincts aren’t in opposition. She is by nature a bridge-builder and unifier, with a talent for smoothing troubled waters. Until recently, one of Dollywood’s main attractions was the Dixie Stampede, a dinner-theatre spectacle which divided the room into North and South before bringing both sides together in a frenzy of patriotic hogwash. In 2017, Slate’s Aisha Harris, who is black, published a critical piece headlined ‘Springtime for the Confederacy‘. Harris called the Dixie Stampede “the Lost Cause of the Confederacy meets Cirque du Soleil. It’s a lily-white kitsch extravaganza that play-acts the Civil War but never once mentions slavery.” With Parton’s blessing, Dollywood’s management promptly reinvented the show by dropping the Dixie label and the blue-and-grey uniforms. When conservative fans protested that she was erasing history, as if the Civil War had involved stunt-riding and unlimited lemonade, Parton responded that she just didn’t want to make anyone feel bad.

Parton does politics in her own way. In 2005, she outraged some of those same fans by writing a song for Transamerica, a movie about a trans woman, and donating another to Love Rocks, a LGBTQ benefit album. It might seem strange to champion minorities while refusing to condemn a president who persecutes those minorities but to Parton, whose Christianity is summed up by the line “Judge not lest ye be judged”, the distinction was clear: she prefers bringing people in to calling them out. It’s the same reason that she acts in a feminist manner yet recoils from that F-word. It’s why, in 1980, she insisted that 9 to 5 wasn’t “women’s lib”, yet staunchly defended Jane Fonda against people who had never forgiven her for her strident anti-war activism. In her life, as in so many of her songs, Parton celebrates understanding and forgiveness as a means of transcending rancour and shame. Her inclusivity is limitless.

Parton can walk this political tightrope because she displays good intentions in everything from her songs to her philanthropy, and her fans fundamentally believe in them. “I’ve never seen the devotion her fans have for her in anyone else,” Fonda says in Here I Am. “It’s quite extraordinary.” In her teaser video for A Holly Dolly Christmas Special, which aired last night to mark her first Christmas album in 30 years, Parton says: “I think that music is a great connector, just is that universal language that everybody enjoys. Right now, during this time, it’s important to put as much love, as much light, and as much joy, as you can out there to the people.” In May, she released a new song called When Life Is Good Again to raise spirits during the pandemic. The song positions her as a healer, promising not only better times to come but a better, warmer, kinder way of living with one another, summed up by this quintessential Parton lyric: “Let’s open up our hearts/ And let the whole world in.” Perhaps it’s a sappy sentiment – but when it comes from Dolly Parton, the great includer, you know it’s not just moonshine.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.