Published in 1900, Bushido: The Soul of Japan changed how the nation was perceived around the world, writes Michiyo Nakamoto.

T

The Last Samurai, a sweeping Hollywood epic, tells the story of Katsumoto, a rebel samurai who dedicates his life to fighting the forces he believes are corrupting Japan’s traditional values. As seen through the eyes of US Army Captain Nathan Algren – who is hired by Japan’s Imperial Army to help fight the rebels, but is taken into captivity by them – Katsumoto and his band of rebel samurai epitomise the honourable warrior: fearless, dedicated to their duty, hard-working and disciplined but also polite and benevolent towards their captive. After witnessing the noble ways of the samurai, Algren switches allegiance to help Katsumoto in his fateful mission.

More like this:

– Why embracing change is the key to a good life

– Is failure the new literary success?

– The best books of the year so far

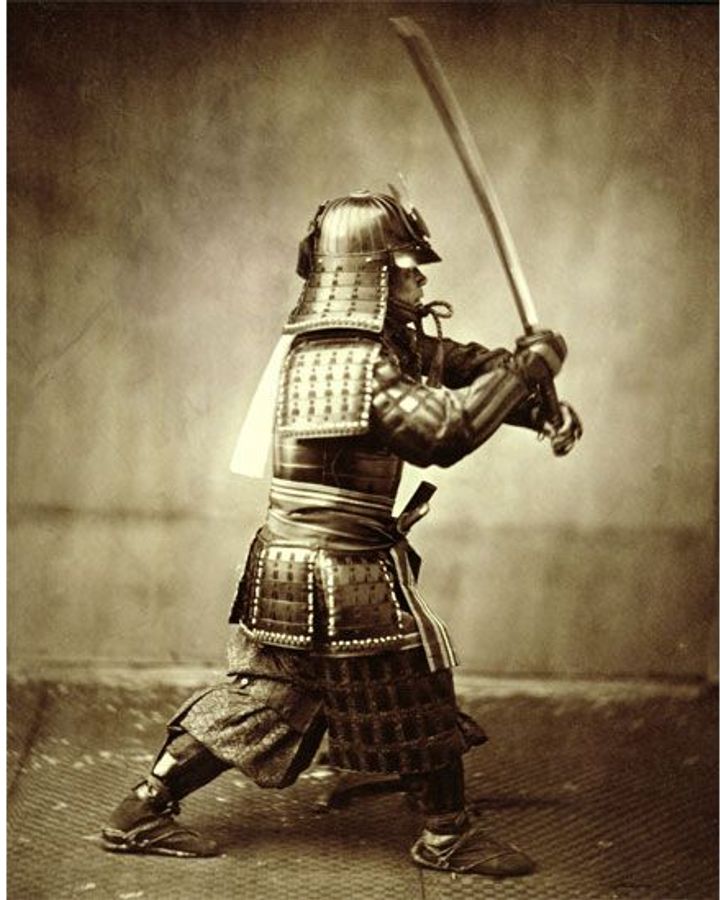

From Hollywood blockbusters to Japanese TV dramas, the samurai has been portrayed over the years as a model of both physical excellence and moral rectitude, for whom honour and loyalty are more valuable than life. This image of the samurai, though not historically accurate, is widely entrenched in the popular imagination, due in no small part to a slim volume written in English at the turn of the 20th Century by Inazo Nitobe.

(Credit: Historica Graphica Collection/Heritage Images/Getty Images)

Bushido: The Soul of Japan, which was first published in 1900 and became an international bestseller in its day, has just been republished as part of Penguin’s Great Ideas series. Although it is one of countless books written on bushido (‘the way of the warrior’), Nitobe’s book remains the most influential source for those seeking to understand a value system that continues to permeate many facets of Japanese society to this day.

How to be good

Through his book, Nitobe, an agricultural economist, educator, diplomat and Quaker convert who was Under-Secretary General of the League of Nations from 1919 to 1929, sought to explain to Westerners (including his American Quaker wife, Mary) the moral values underpinning Japanese culture.

Nitobe traced those values to bushido, which he defined as the samurai’s code of moral principles. Bushido, according to Nitobe, instructed the samurai to have a strong sense of justice and the courage to carry out that justice. It preached benevolence and politeness, truthfulness, honour and loyalty to a higher authority. “The sense of honour, implying a vivid consciousness of personal dignity and worth, could not fail to characterise the samurai…” Nitobe wrote.

The reality was somewhat different, and historians have criticised Nitobe’s description of the samurai as highly romanticised. “Samurai and daimyo (feudal lords) weren’t really living the life of honour and loyalty,” says Sven Saaler, professor of modern Japanese history at Sophia University in Tokyo. “If the opportunity arose, they would also kill their master and take his position.”

In his seminal work, Nitobe, who came from a family of samurai, also claimed that the samurai’s values were shared by all in Japan. “(The) spirit of bushido permeated all social classes,” Nitobe wrote. Contrary to Nitobe’s claim, by the Edo period (1603-1868) samurai came to be reviled for abusing their privileges at a time when their martial skills had become obsolete due to two centuries of social stability.

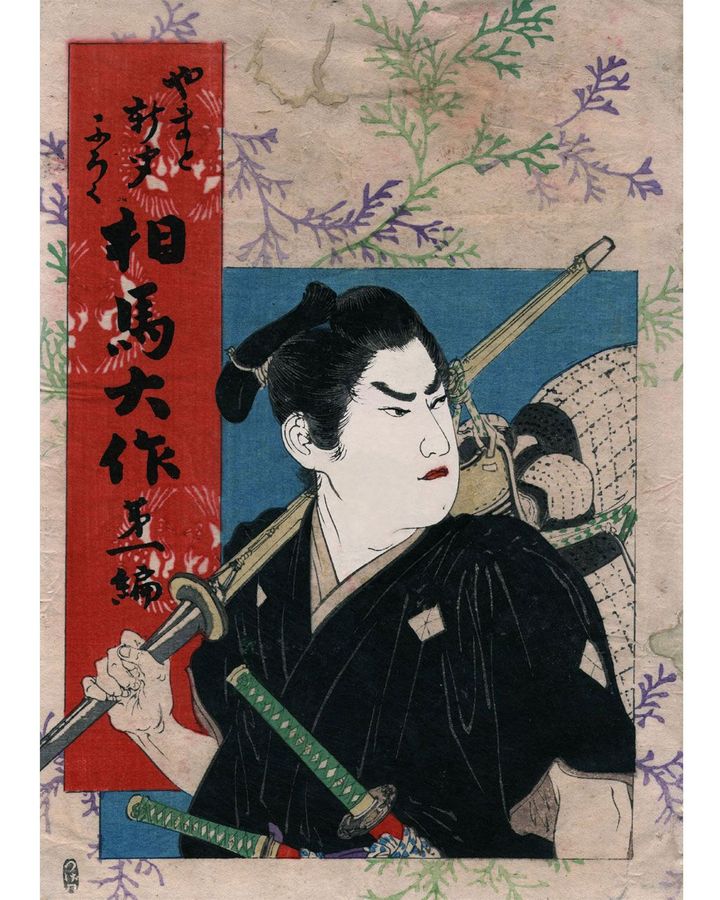

(Credit: Kusakabe Kimbei/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

However, Nitobe’s aim in writing his book was not to provide a historically accurate account of the samurai, but to show the outside world that Japan had a value system that was similar to Christian morality. As such, Nitobe made constant references to European philosophy and literature and likened bushido to the chivalry of European knights.

“Chivalry is a flower, no less indigenous to the soil of Japan than its emblem, the cherry blossom….” Nitobe wrote. According to Saaler, Nitobe sought to counter racism and fears in the West of the ‘Yellow Peril’ by shaping the image of the samurai, and by extension, the Japanese, as not only brave but also chivalrous. Just four years before his book’s publication, Japan had emerged victorious in its war against China from 1894 to 1895. That military success, which stunned the Western powers of the time, was quickly followed by Japan’s victory in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904 and 1905.

Staking a claim

Nitobe’s book aimed to counter fears that Japan would one day become a threat to Europe and “to construct a very positive image of Japan as a militarily strong but civilised country that behaved in a civilised way in war,” says Saaler. According to Eri Hotta, a historian and author of Japan 1941: Countdown to Infamy, the book was also “an attempt to place Japan on an equal footing with the best of the Western powers so that they could claim a right to be masters of colonies”.

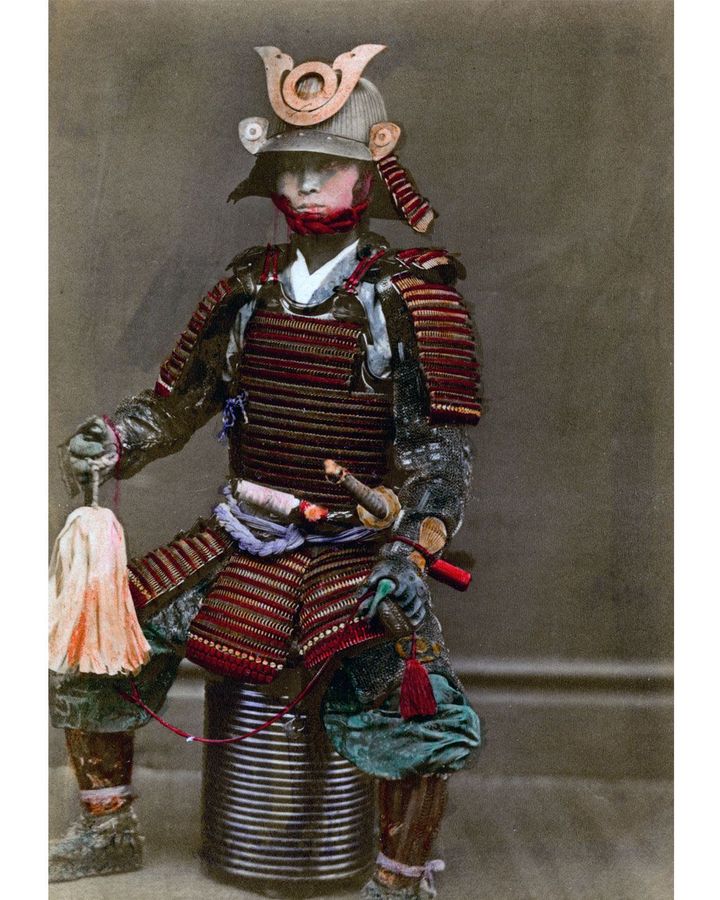

(Credit: Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

The international acclaim that greeted his book suggests Nitobe succeeded in his objective of documenting Japanese values and thereby improving the country’s image in the West. Appearing at a time when interest in Japan was growing, following its military victories over China and Russia, Nitobe’s book found a willing audience among Western readers who were both impressed and mystified by Japan’s stunning rise.

To Western readers, the courage, moral rectitude and other values of bushido described in Nitobe’s book provided a compelling explanation for how a small, and hitherto unknown, country could defeat its much larger and seemingly more powerful neighbours. “Nitobe’s book offered a way to explain the source of Japan’s growing power,” says Lance Gatling, author of the upcoming The Kano Chronicles, about Jigoro Kano, the founder of judo. “It was one of the first Western books on Japanese culture, and it sold like crazy.” Gatling found a copy of Bushido in the Arkansas Public Library that had been printed in 1904, just four years after its initial publication.

The allure of bushido as a moral code even caught the attention of the then US President, Theodore Roosevelt, who was a keen judo practitioner. In a letter to the diplomat and politician, Count Kentaro Kaneko, dated 13 April, 1904, Roosevelt wrote: “I was most impressed by the little volume on Bushido. I have learned not a little from what I have read of the fine Samurai spirit…”

(Credit: Sean Sexton/Getty Images)

Robert Baden-Powell, founder of the Boy Scouts, wrote that one aim of the Boy Scouts scheme was “to revive some of the rules of the knights of old, which did so much for the moral tone of our race, just as …Bushido… has done, and is still doing, for Japan.” In contrast to the rapturous reception it received overseas, the book was widely criticised in Japan as inaccurate, according to Oleg Benesch in his book Inventing the Way of the Samurai.

Nevertheless, its international success was celebrated in Japan, and by planting the idea that Japan’s moral rectitude gave it the right to join the privileged group of Western colonial nations, Nitobe’s book “made Japanese believe that they were all inheritors of superior values and that they had a claim to right the wrong,” noted Hotta. “It was important for the Japanese self-image.”

(Credit: The Print Collector/Print Collector/Getty Images)

After World War Two, bushido, which was associated with Japan’s militarism, became “a target of popular resentment” within Japan, wrote Benesch. More recently, bushido has seen renewed interest and Nitobe’s book gained international recognition again in the 1980s, when the world sought to understand the source of modern Japan’s rapid economic and technological advances. Lee Teng-hui, the recently deceased former President of Taiwan, reminded the Japanese public of the book’s significance in a 2006 memoir detailing how it influenced his own life and thinking.

Yet, apart from such intermittent bursts of interest, Nitobe and his former best-seller are not household names in Japan. Even those who remember Nitobe identify him more often as the face on the 5,000 yen note from 1984 to 2004.

Many of the values he identified as the teachings of bushido – politeness towards others, a high regard for personal honour, self-control and loyalty to a higher authority – remain core to the Japanese view of proper behaviour. Bushido is widely invoked in sports, with the Japanese national baseball team nicknamed ‘Samurai Japan’, and the national men’s football team called ‘Samurai Blue’.

But the prevalence of bushido values in Japanese society is a reflection of the continuing influence of Confucianism rather than Nitobe’s book, according to Yukiko Yuasa, assistant professor at Teikyo Heisei University in Tokyo. “Many of the teachings that appear in Nitobe’s book are part of Japanese behaviour, so people don’t have to read the book to learn about those values,” she says.

Nevertheless, Nitobe’s book continues to inform the outside world of values that remain core to Japanese society. As such, Bushido: The Soul of Japan can be expected to help shape the world’s understanding of Japan for many years to come.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.