You’ve probably heard of the Dead Sea Scrolls and seen King Tut’s mask. But if you want to beat your family at Jeopardy, you’d better learn their backstories. Here’s our cheat sheet for six iconic artifacts from the ancient world.

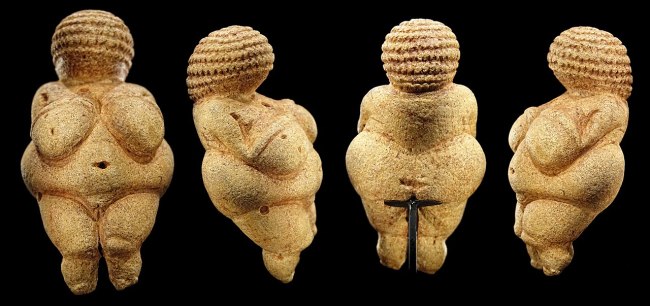

Venus of Willendorf

(Credit: Bjorn Christian Torrissen/Wikimedia Commons)

From: Around 30,000 years ago, Austria

Now: Natural History Museum Vienna in Austria

Short, fat and 30,000 years old, Venus of Willendorf is the female icon of the Ice Age. The four-inch-tall figurine bears pronounced breasts, buttocks, belly and vaginal lips, but lacks feet or facial features. Braids, or perhaps a knit cap, cover her head, and specks of pigment suggest the tan limestone artifact was once painted red.

Archaeologists found the figurine in 1908, about a week into excavations at Willendorf II, an Austrian site along the Danube River, roughly 50 miles from Vienna. Throughout the 1900s and 2000s, several other digs occurred there, with ever-improving methods, which unearthed two less-famous Venus figurines and hundreds of stone tools.

Across Europe, nearly 200 similar statuettes have surfaced from sites between 23,000 and 40,000 years old. Although modern scholars call these artifacts Venuses, after the Roman goddess of love and fertility, the actual sculptors lived at least 20 millennia before Classical Rome. It’s unclear why Ice Age people carved these figurines, with researchers proposing they served as fertility symbols, self-portraits or pornographic items. In any case, the supposed sex appeal didn’t last: On a 5 point scale from unattractive to extremely attractive, Venus of Willendorf received an average rating of 0.14 in a 2011 survey of 161 undergraduates.

Olmec Colossal Heads

(Credit: Fer Gregory/Shutterstock)

From: Starting about 3,400 years ago, Gulf Coast, Central America

Now: Several Mexican museums, including Mexico City’s National Museum of Anthropology

Sometimes called the mother culture of Mesoamerica, the Olmec civilization rose from the swampy forests of the Mexican Gulf Coast between about 400 and 1,400 B.C. Two millennia later, in A.D. 1862, a farmer digging the same land struck a colossal stone head. It was the first of 17 similar heads yet to be recovered, thought to be portraits of Olmec rulers.

The imposing statues stand between 5 and 10 feet tall, each weighing more than a full-grown elephant. They portray surly men with almond-shaped eyes, flat noses and plump lips. But each head wears a unique visage, expression and headdress, supporting the idea that the carved boulders depict particular leaders.

The first accidental discovery occurred at Tres Zapotes in the foothills of the Tuxtlas Mountains, which provided the basalt stone used to make them. But archaeologists later uncovered most of the heads nearly 60 miles from the basalt source, at the ancient capitals of San Lorenzo and La Venta. Though surely laborious, it remains unclear how the Olmec transported these massive boulders, eventually carved and displayed in central plazas. And, several heads seem to have been broken and buried long ago, leading some archaeologists to think ancient people deliberately destroyed old statues as new rulers seized power.

King Tut’s Funerary Mask

The burial mask of King Tut. (Credit: Mark Fischer/Flickr)

From: 3,300 years ago, Egypt’s New Kingdom

Now: The Egyptian Museum in Cairo, Egypt

Say pharaoh and most people will imagine the funerary mask of King Tutankhamun. The 24-pound facial replica capped the wrapped mummy of the Egyptian king, who died in 1324 B.C. at the age of 19, after ruling just 9 years. The solid gold base glints with lapis lazuli, turquoise and other semiprecious stones. The chin sprouts a tube-like beard, and the forehead displays a vulture and cobra, deities who together symbolized unification of Lower and Upper Egypt.

The mask reemerged to the modern world in 1922, when British archaeologist Howard Carter discovered King Tut’s nearly intact tomb in the Valley of the Kings, a royal burial ground along the Nile River. Over the ages, modern and ancient looters emptied most Egyptian royal tombs, so Tut’s burial chamber was the first to reveal the phenomenal wealth pharaohs took the grave.

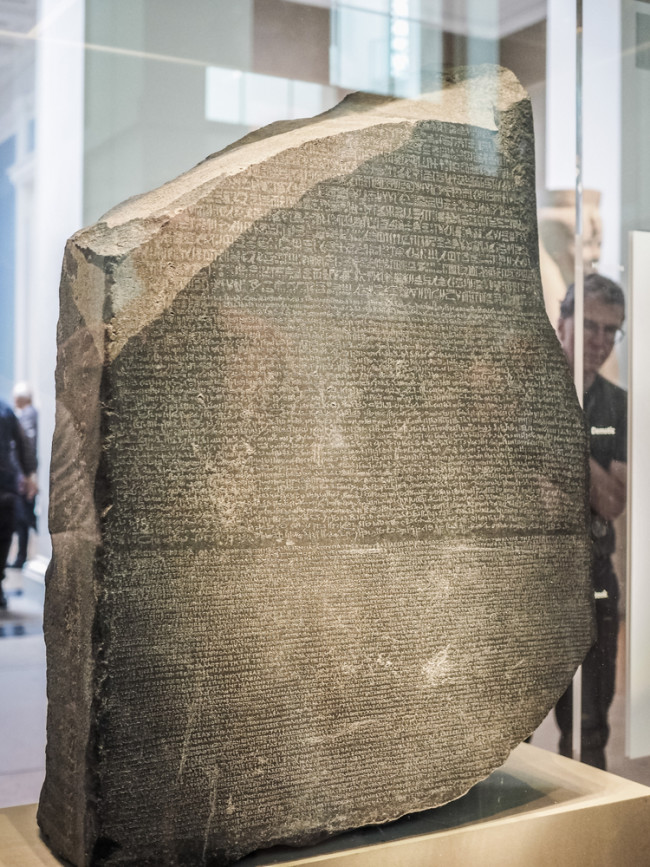

Rosetta Stone

(Credit: Claudio Divizia/Shutterstock)

Then: 2,200 years ago, ancient Egyptian city of Rosetta

Now: The British Museum, England

Honestly, the Rosetta Stone is a boring read, a priestly decree issued in 196 B.C., affirming the divine cult of King Ptolemy V on the first anniversary of his coronation. But its scribe chiseled the message into the black slab three times in a row in different scripts: Ancient Greek, Ancient Egypt’s formal hieroglyphs and its more casual, cursive demotic script. And that bilingual, tri-script inscription enabled decipherment of Egyptian hieroglyphs, unlocking all of the ancient civilization’s writings.

Discovered in 1799 by French soldiers during Napoleon’s campaign in Egypt, the artifact wound up in London after British troops defeated the French there in 1801. Ancient Greek was understood, so scholars and the public immediately recognized the stone’s potential for deciphering hieroglyphs. But it would be another 20 years before Jean-Francois Champollion successfully cracked the code.

The most popular item in the British Museum today, the relic measures 3 feet 9 inches and weighs 1,680 pounds, though about a third is missing, knocked off over the ages. The full text is still known, however, because other monuments bear the same decree.

Terracotta Army

From: 2,200 years ago, Shaanxi Province, China

Now: Museum erected at the site, Emperor Qinshihuang’s Mausoleum Site Museum

Imagine building your tomb for more than 30 years — fueled by limitless power, resources and yearning for immorality. Even then your mausoleum might not compare to the complex commissioned by Qin Shihuang, the first emperor to rule a unified China from 210 to 221 B.C. According to ancient Chinese texts, more than 700,000 laborers worked for the site, which sprawls 22 square miles, far more land than most college campuses (all but three in the U.S., in fact).

The site features statues of dancers and acrobats, gold-embellished carriages and bronze waterfowl in diorama-like canals. But it’s perhaps best known for the Terracotta Army, thousands of life-sized clay warriors, lining trenches in military formation. In 1974, farmers digging a well discovered the first statue. Since, three major excavations have uncovered 2,000 additional soldiers, although another 6,000 likely remain buried. Each statue seems to portray a real soldier in Qin Shihuang’s force, based on their individual hairdos, caps, tunics, facial hair and functioning bronze weapons, which remain remarkably sharp to this day. Even their ears are unique, according to a 2014 study in the Journal of Archaeological Science.

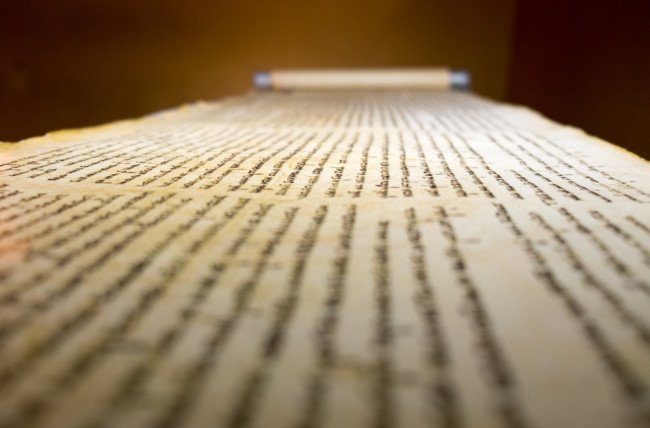

Dead Sea Scrolls

(Credit: Lerner Vadim/Shutterstock)

From: About 2,000 years ago, Dead Sea shores in West Bank and Israel

Now: The Israel Museum, Jerusalem

In 1947, Muhammed ed-Dib, a Bedouin shepherd, went searching for a stray goat along craggy cliffs banking the Dead Sea. What began as a goat pursuit resulted in one of the greatest archaeological discoveries of the 20th century: In a narrow cave, ed-Dib discovered clay jars stuffed with ancient scrolls — the first of nearly 1,000 tattered texts written between 200 B.C. and A.D. 65 that comprise the Dead Sea Scrolls.

About 200 of the scrolls transcribe stories in the Hebrew Bible or Christianity’s Old Testament — though these copies likely predate the Bible’s compilation. The rest contain other religious texts, like prayers, hymns and rules. Though mostly written in Hebrew, the archive also features older paleo-Hebrew, several Aramaic dialects, Greek, Latin and Arabic.

Over the years, archaeologists have recovered many more scrolls from 12 caves near the first trove and a few more distant spots. Thanks to the briny desert conditions, some scrolls aged intact. But most deteriorated, constituting a corpus of more than 25,000 bits of parchment and papyrus. Like a jigsaw puzzle — with innumerable missing pieces — fragments have been painstakingly reassembled by matching handwriting and materials. In the future, DNA sequencing could help because many scrolls are made of animal skins. The method, tested on 26 fragments in a 2020 Cell paper, successfully matched scraps from the same creature.

From what can be read, researchers debate the scrolls’ authors. Some say the texts came from diverse sources; others attribute them all to a Jewish sect that lived near the 12 caves in the first century A.D.