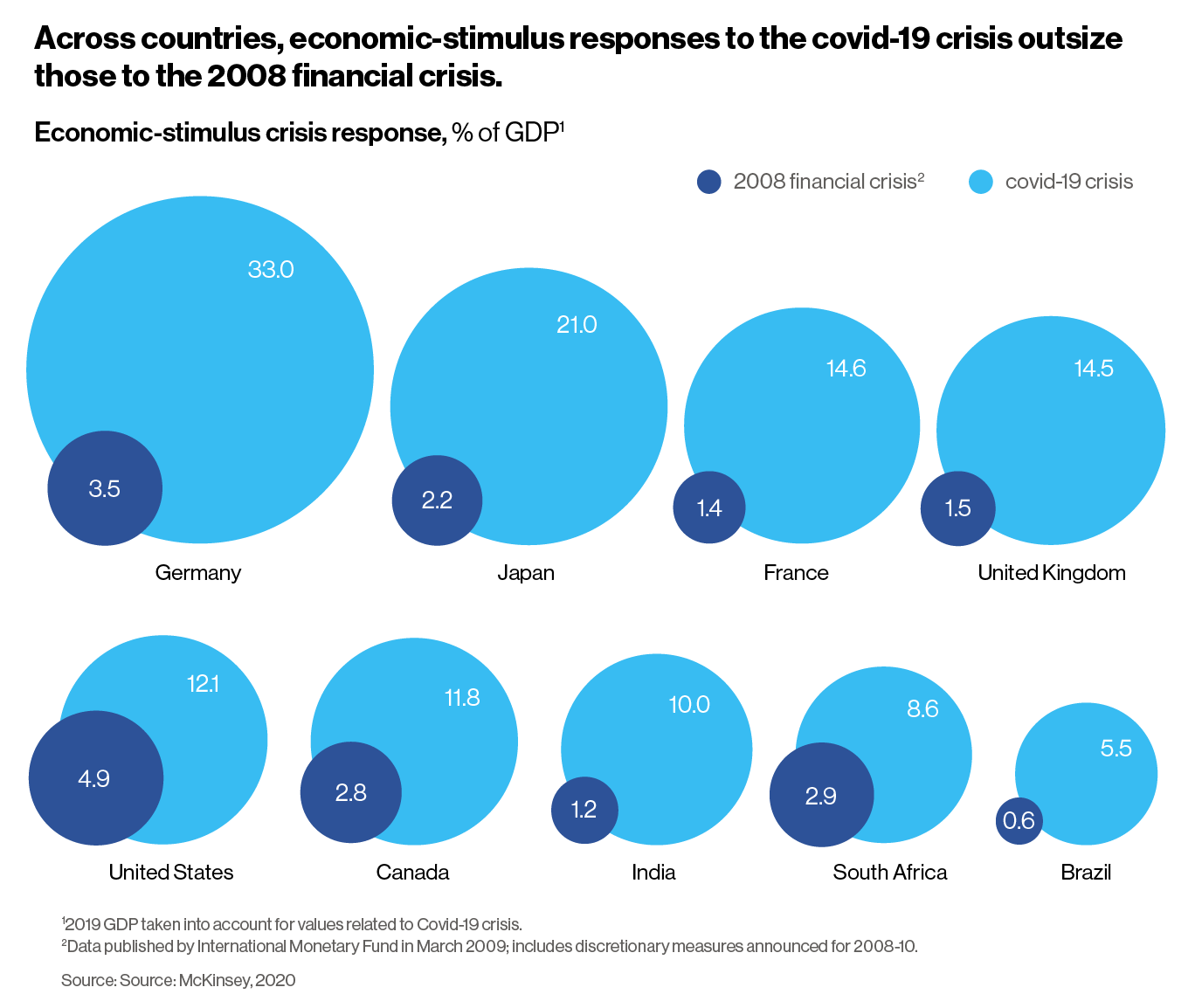

Over the past six months, central banks and governments have unlocked financial floodgates to deal with the economic fallout of covid-19. As early as April, 106 countries had introduced or adapted social protection programs, mostly cash transfers, to help those affected by the pandemic. A McKinsey analysis of 54 countries estimates that governments had committed $10 trillion by June, through grants, loans, and furlough payments to unemployment benefits and welfare. The quantities far outstrip the 2008 financial crisis (see chart).

This article was written by Insights, the custom content arm of MIT Technology Review. It was not produced by MIT Technology Review’s editorial staff.

Running parallel to this state spending spree is a full-bodied embrace of digital finance by citizens. Paper cash and coins are potential vectors for the virus (one municipal authority in India even banned the use of paper cash for home deliveries). The movement to online commerce helped millions of consumers grow accustomed to digital spending, and they will not likely return.

A once-in-a-generation cash infusion

Some forward-looking governments and central banks are combining the two, by using digital technology to disburse funds quickly and efficiently, and unlocking more data about the shape of the economic recovery. Experimental policymakers are using this once-in-a-generation cash infusion to reimagine how governments make payments to citizens.

In Hangzhou, China, municipal authorities are working with Alibaba, headquartered there, to launch a digital-coupon stimulus program via the Alipay platform. Coupon-based recovery initiatives are not new–the city used a paper scheme during the 2008 crisis–but releasing them digitally, in a real-time lottery, allows the government to analyze how coupons are spent, unearthing data about the economic recovery. Unlike paper, digital coupons are flexible; the number, value, and thresholds at which they are used are adjustable over time, allowing authorities to shift them to sectors most in need. The program has been replicated in more than 100 cities across China.

China was already a frontrunner in digital finance. The digital yuan is on track to be the world’s first sovereign digital currency and is currently in pilot mode with four state-owned commercial banks. But many other countries are funneling stimulus funds through digital pipes. Malaysia’s federal government disbursed $110 million to almost half the population via three e-wallets–Grab, Boost, and Touch ‘n Go–helping jumpstart the digital payments industry.

Ghana, the first country to launch a covid-related digital financial services policy, has removed fees on low-value remittances, relaxed transaction and wallet size limits for mobile money, enabled authentication processes to be transferable from SIM registrations, and cut rates on interbank transactions. Neighboring Togo built a digital cash transfer program called Novissi, providing monthly aid to informal sector workers. Cash transfers are paid out every two weeks into a mobile money account, at $21 for women and $19 for men. Despite the challenges of reaching beneficiaries who, by definition, lack paperwork and authentication documents, the project was assembled in just 10 days, using the national voter database, to serve 12% of the population. It has since evolved to focus more on specific parts of the country, unfolding policy choices like district-level movement restrictions.

Just as Togo used existing assets such as the voter database, other countries have built covid payments on infrastructures already in place. In Chile, a national ID-linked service, CuentaRut, supports low-income people, and it has been used to channel payments of the government’s “Bono covid-19” emergency assistance funds into the bank accounts of more than 2 million citizens. Peru is scaling up its government-to-citizen system to increase payments to existing and new beneficiaries, working with new financial service providers, including private banks and mobile money companies.

This all stands in contrast to the United States, the world’s largest, most technologically sophisticated economy, which has remained in the payments dark ages; an estimated 70 million American families turned to bank overdrafts, payday loans, and check cashers while they waited for paper checks to arrive in the mail.

Governments are also reducing the frictions, fees, and charges that bog down the system. In Italy, from July 2020, merchants below a revenue threshold of EUR400,000 ($471,000) are entitled to a tax credit equal to 30% of the commissions on electronic payments, while Egypt’s central bank has raised the limit for electronic payments via mobile phones for individuals and companies.

Nongovernmental organizations and companies are helping. Kenya’s Safaricom has partnered with public transport companies to let them accept cashless payments through M-Pesa, the country’s ubiquitous mobile wallet. SumUp, a fintech specializing in payment solutions for small and medium-sized businesses, signed an agreement with the Italian Red Cross to supply SumUp card readers throughout the country. Paga, a Nigerian mobile payments company, has waived fees for merchants. Anything that quickens the movement of money will have far-reaching effects at a time when businesses exist on a solvency knife edge.

Hayek, meet Keynes

Untangling the short- from long-term changes wrought by covid-19 is difficult. Some reforms, such as government reimbursement of telehealth consultations, may be reversed when the crisis abates. But there will be some fundamental shifts in the financial landscape, particularly with the pandemic adding momentum to major financial reforms already underway: the development of central bank digital currencies (CBDCs).

These digital fiat currencies have many appealing features. They could support citizens more efficiently, quickly, and flexibly than current approaches like check payments or tax relief. They are programmable and adjustable to control how, when, and where funds are used. A CBDC could function as an account that a person holds with a central bank, with tech companies, fintechs, or intermediaries developing user-friendly interfaces.

Other benefits include the production of real-time data about economic activity, more accurate and timely data for gross domestic product estimates, near-instantaneous payment settlement, and greater traceability for tackling corruption and financial crime. CBDCs effectively afford all of the efficiency gains of digital finance, such as speed and reduced processing, without ceding regulatory controls. They could also address two big concerns about private cryptocurrencies: money laundering and tax evasion. In fact, they might assist treasuries in combatting nonpayment of some taxes, augmenting their revenues.

Best thought of as a regulated cryptocurrency, the idea has attracted interest from central banks and policymakers in the Netherlands, France, Canada, and Singapore, as well as the International Monetary Fund. Dutch bank ING reckons covid-19 makes CBDCs “more likely” and the Facebook-affiliated Libra Association’s “Plan 2.0,” published in April 2020, argued that CBDCs could be integrated with the Libra global digital currency network.

The key, says Zhiguo He, Fuji Bank and Heller Professor of Finance at the University of Chicago, is to use digitally delivered state money in a sophisticated and market-oriented way. “Government-to-person payments are exactly what happened in 1950-to-1970s China, during the planned economy. We know it went badly and that markets are the solution. Payment itself is therefore not the key for economic stimulation: information is.”

Professor He, who serves on the academic committee of the Luohan Academy, expects social protection and stimulus payments prompted by the pandemic to permanently upgrade the digital delivery of government-to-person payments, but he also argues that digital currencies are best viewed as a means, not an end. “From the perspective of an economist, the ‘first best’ is to have a system where we have all the information to calculate the fiscal multiplier for that person–how much GDP can be generated by giving one dollar to that person, taking into account of savings, the goods he/she is purchasing and so on–and send the first dollar to those with the highest multipliers. The digital currency itself is just a small part of this ideal world.”

Policymakers’ first concern is to get financial aid to those who need it. Using digital technology could help them not just give money away faster and more efficiently, it could also help them understand the state of the economy and adjust support measures to target the critical trouble spots.

______________________________

The Luohan Academy‘s mission is to understand how digital technology can help achieve the common good and build a broad academic community for systematic and in-depth research into solving first-order problems in the digital society. Visit the website for analysis and ideas covering issues including pandemic-era policymaking, fintech, and country analysis.