As a schoolboy growing up in New York City in the 1870s, Herman Hollerith often managed to sneak out of the schoolroom just before spelling lessons. His teacher noticed and one day locked the door; Hollerith responded by jumping out of the second-floor window. Difficult, easily bored, but clearly brilliant, Hollerith gained admission to the School of Mines of Columbia College (now the School of Engineering and Applied Science) and graduated with distinction and an engineering degree in 1879. He was 19.

One of his Columbia professors, William P. Trowbridge, invited Hollerith to join him in Washington, DC. Trowbridge had been appointed as a chief special agent for the 10th (1880) US Census and was responsible for the Report on Power and Machinery Employed in Manufactures. He hired Hollerith to write the section titled “Steam and Water Power Used in the Manufacture of Iron and Steel.”

But being the kind of person who easily got bored, Hollerith found that working on the report wasn’t enough. So in his spare time, he worked for John Shaw Billings, head of the census office’s Division of Vital Statistics. It was there that Hollerith got the idea to mechanize the repetitive tabulations involved in census work. Billings suggested that it might be possible to store information about people as notches in the sides of cards. This wasn’t such a revolutionary idea: the Jacquard loom used punch cards to control weaving patterns, Charles Babbage had envisioned using punch cards for his Analytical Engine, and a player piano that played music as dictated by holes in a long roll of paper had been demonstrated at the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia in 1876.

Hollerith thought a census machine might have great commercial potential, and he asked Billings to join him in a venture to develop and commercialize it. Billings declined; drawn to organizing information rather than mechanizing it, he would go on to become the first director of the New York Public Library. But Francis Amasa Walker, the head of the 10th census, likely found Hollerith’s idea extremely interesting.

Walker, who’d been born to a wealthy Boston family and went to Amherst, was highly regarded for his work in economics and had been appointed chief of the US Bureau of Statistics in 1869, after serving in the Civil War as an enlisted soldier and then a commissioned officer in the Union Army. Nominated to be superintendent of the ninth (1870) census at age 29, he set out to reform the census by making it more scientific and efficient–and by eliminating the influence of politics on the official statistics. He didn’t reach that last goal, but his work was so well respected that he was appointed superintendent of the 10th census in April 1879.

In the fall of 1881, Walker left government service to become the third president of MIT. The following year, he and George F. Swain, an instructor in civil engineering, persuaded Hollerith to join the MIT faculty. Hollerith taught a senior mechanical engineering course that “took in hydraulic motors, machine design, steam engineering, descriptive geometry, blacksmithing, strength of materials, and metallurgy, among other subjects,” according to his biographer, Geoffrey Austrian, who wrote Herman Hollerith: Forgotten Giant of Information Processing. The Tech called him “energetic and practical.”

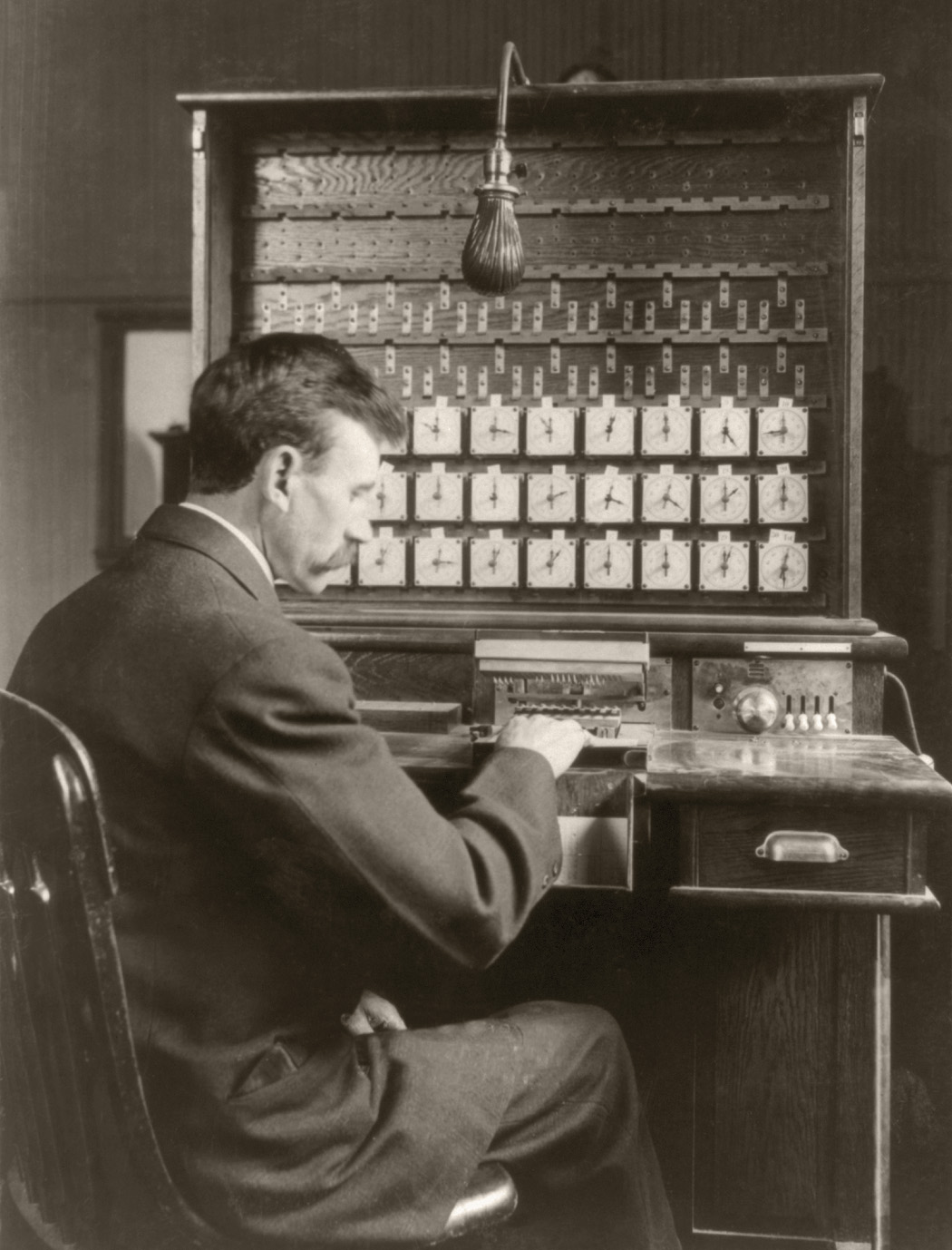

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

While at MIT, Hollerith made what he would later call his “first crude experiments” on the census machine. Like the player-piano roll, his first approach involved punching holes in a long strip of paper, in this case with one row for each person.

But Hollerith wasn’t cut out for academia. Not wanting to teach the same course a second time, he left the Institute at the end of the spring semester, accepting an appointment as an assistant examiner at the US Patent Office in May 1883. He likely took the job to learn firsthand how the US patent system worked. Hollerith resigned his appointment less than a year later, on March 31, 1884, and set up his own office as an “Expert and Solicitor of Patents.” That September, he filed patent application 143,805, “Art of Compiling Statistics.”

Hollerith’s original patent application focused on the idea of storing data on a long strip of paper. But at some point–the timing is unclear–he had taken a trip out West and noticed a train conductor punching each rider’s ticket to indicate that person’s sex and hairstyle, a clever strategy to prevent the sharing of multi-ride tickets. That idea of creating what was called a “punch photograph” stuck with him. And by the time his patent was issued on January 8, 1889, Hollerith had settled on using cards made out of stiff paper instead of paper strips. His three “foundation” patents–all issued on the same day in 1889–describe a complete system for mechanizing the computation of statistics, including a device for punching cards in such a way that the punches correspond to a person’s age, race, marital status, and so on, and a device for electrically counting and sorting the cards using wires that descend through the holes into little cups filled with mercury, activating relays to open and close doors on a sorting cabinet. Electromechanical counters tracked the number of cards that matched particular criteria.

The system was first used to compile health statistics by the City of Baltimore, the US Office of the Surgeon General, and the New York Health Department–all opportunities probably secured with the help of Billings.

In 1889, the census office held a competition for a contract to deliver machines that would be used to tabulate the 11th (1890) census: Hollerith’s system won. As the work on that census progressed, Hollerith worked out the basics of a business plan that would last for more than a century. Because he didn’t want poorly maintained machines to give his company a bad name, he rented the machines to his customers and included both service and support. After the census office used inferior paper cards that left fibers in the mercury, Hollerith required his customers to purchase his own high-quality cards.

Hollerith incorporated his company as the Tabulating Machine Company in 1896; in 1911 he sold it for $2.3 million to the financier Charles R. Flint, who combined it with three of its competitors to create the Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company (CTR). In 1914 CTR hired Thomas J. Watson Sr. as its general manager. Eight years later, Watson renamed the company International Business Machines.