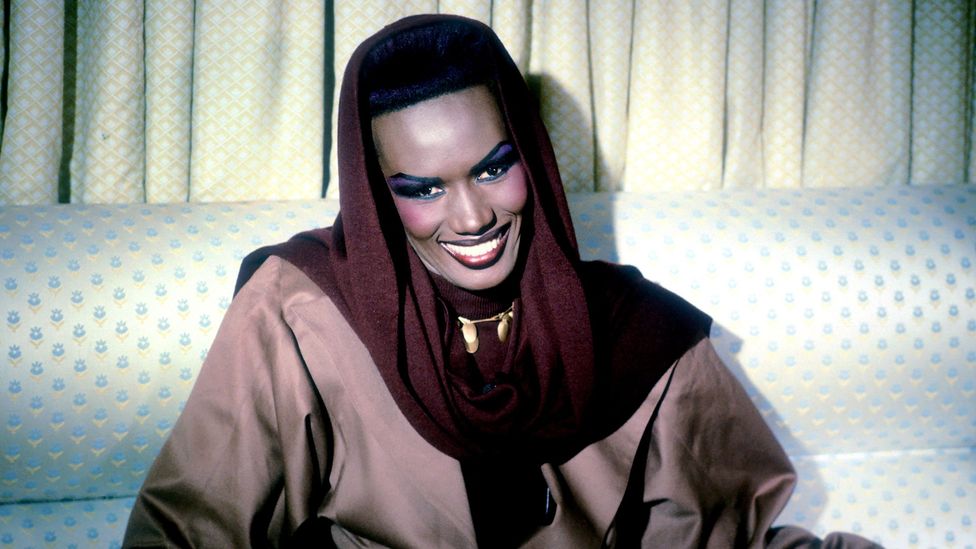

She may be a style icon and all-round star. But 40 years on from her seminal LP Warm Leatherette, she should be recognised foremost as a musical trailblazer, writes Nick Levine.

I

It’s difficult to describe Grace Jones without using words that have been dulled into cliche, but the revered Jamaican performer really is iconic, unique and visionary. It’s equally tricky to sum up succinctly what she does: since she began flexing her creative muscles in the late 1960s, Jones has been a stage actress, high-fashion model, disco singer, photographer’s muse, new wave musician, film star and perennial trend-setter. Clearly, Jones’s chameleon-like qualities are a key part of her appeal. “She takes you to higher vibrations through her presence alone – she frees you completely because she is free herself,” says Honey Dijon, an internationally renowned DJ-producer who counts Jones as a major inspiration.

More like this:

– The Picassos of modern music

– Is Lady Gaga a genius or copycat?

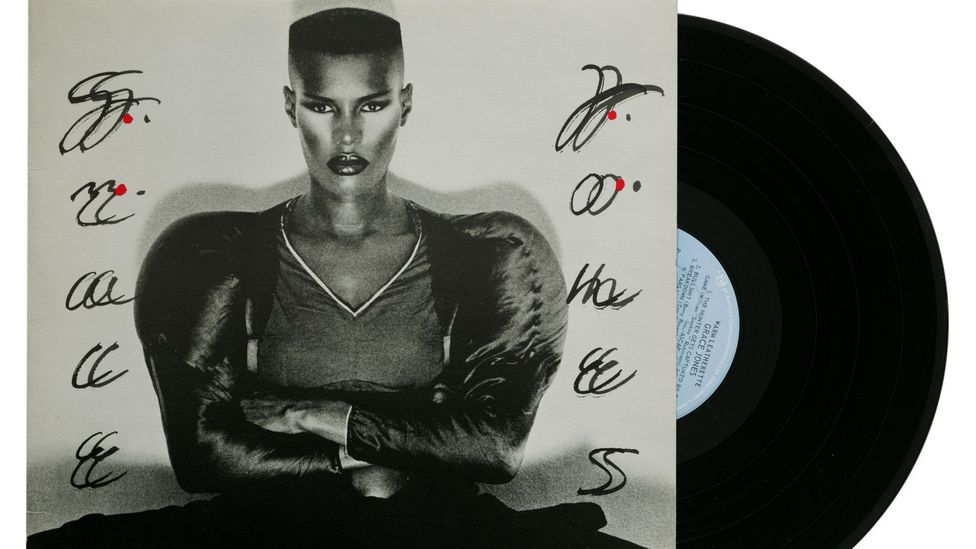

At the same time, Jones’s incredible creative fluidity means her achievements in certain fields – especially music – are easy to underestimate. The dazzling, androgynous looks she’s created for photo shoots and album covers are rightly acclaimed – Vogue calls her “the ultimate fashion muse”, while Dazed has hailed her “revolutionary style moments” – but at the expense, perhaps, of her musical legacy. Warm Leatherette, the album that introduced Jones’s distinctive, reggae-flecked take on new wave, has just turned 40 years old, so it’s an apt time to reassess her contribution as a singer, songwriter and genre-blending innovator. Featuring punky covers of songs by artists as varied as Tom Petty, Smokey Robinson and Roxy Music, all sung in Jones’s majestically detached style, it’s a record as fearless and singular as Jones herself. And also like Jones, it’s strangely ageless, sounding almost as fresh today as it did in 1980.

40 years old this year, Jones’s album Warm Leatherette introduced her distinctive sound, a reggae-flecked take on new wave (Credit: Alamy)

Admittedly, in recent years Jones hasn’t shown much interest in adding to this musical legacy – 2008’s Hurricane is the only album she’s released in the past 30 years – but plenty of artists are celebrated long after their output grounds to a halt. Dr Kirsty Fairclough from the School of Arts and Media at the University of Salford says Jones’s “expression of self through several art forms” has “reframed our understanding of the pop performer”, but hasn’t been “fully recognised in pop culture” yet. She points to “echoes” of Jones’s work in musicians as varied as Nicki Minaj, Lady Gaga, Rihanna, FKA twigs, Grimes, Roisin Murphy and Janelle Monae.

Because Jones has so successfully subverted gender norms – the famous cover art for her 1985 compilation album Island Life, created by her then-partner and frequent collaborator Jean-Paul Goude, presents her as an almost impossible paragon of athleticism – she’s also an enduring queer icon. “She taught me not to be afraid of anything – that life is a stage, and the stage is the place for the extravaganza that comes from within,” says queer Belgian performance artist and pop musician Dolly Bing Bing. Zebra Katz, a pioneer of the queer rap genre, says Jones has “been one of the key figures in stabilising a creative bar for most of my work”, hailing her ability to “shine through in whatever she presents” – from “acting in Hollywood films to walking runways in Paris and creating some of the world’s most unique and identifiable music”.

Jones’s influence as a musician was due to be celebrated at this month’s Meltdown festival in London, which she was asked to curate by the Southbank Centre, Europe’s largest arts institution. “She was the first artist who made me feel that I could express myself, be whatever I wanted to be, and not be afraid of what the world might say,” said Bengi Unsal, Southbank Centre’s head of contemporary music, when Jones was announced as curator in November. Though this year’s festival obviously won’t be going ahead because of coronavirus, Southbank Centre has confirmed that Jones will take charge of the 2021 festival instead. When she does, she’ll become the first black woman to oversee the 10-day event, which has previously been curated by the likes of David Bowie, Yoko Ono and David Byrne.

A milestone month

Even with her Meltdown festival on hold, June 2020 is something of a milestone month for Jones because it marks the 40th anniversary of her first British hit. On 27 June 1980, around six weeks after Warm Leatherette was released, Jones dropped its third single: a thrillingly minimal cover of The Pretenders’ Private Life which cracked the UK top 20 and introduced her to a wider audience when she performed it, magnificently, on Top of the Pops. Zebra Katz says it’s his favourite song on Warm Leatherette – “Grace’s voice has such a relaxed and controlled attitude and the track itself is just so incredibly lush” – and The Pretenders’ Chrissie Hynde is also a big fan. “When I first heard Grace’s version I thought ‘Now that’s how it’s supposed to sound!'” she wrote in the liner notes for Jones’s 1998 compilation Private Life: The Compass Point Sessions.

FKA Twigs is one of countless pop musicians to bear the influence of Jones (Credit: Alamy)

Musically, Warm Leatherette was a bold volte-face after Jones had launched her recording career with a trio of disco albums – 1977’s Portfolio, 1978’s Fame and 1979’s Muse – produced by remix pioneer Tom Moulton. Jones’s disco era was moderately successful and proved she wasn’t just a fashionista dabbling in music. By this point, she’d already defied industry expectation to establish herself as a high-fashion model. Jones, who moved from Jamaica to Syracuse, New York, as a teenager, signed her first modelling contract at the age of 18. She then walked runways for Yves Saint Laurent, Kenzo and Azzedine Alaia during a successful spell in Paris in the early 1970s, when she shared a flat with Jerry Hall and Jessica Lange. In her 2015 book I’ll Never Write my Memoirs, Jones recalls being confronted by blatant racism when she arrived in the French capital. A leading agent told her that “selling a black model in Paris is like trying to sell them an old car nobody wants to buy”, but Jones wasn’t put off, replying prophetically: “I’m going to make you eat those words”.

Still, Jones was never too enamoured with her modelling career, which she describes in I’ll Never Write my Memoirs as “throwaway”, so she soon parlayed her growing visibility into a viable music career. Her club-ready cover of Edith Piaf’s La Vie en Rose became a big hit in continental Europe in 1977; shortly after, a remixed version of her 1975 debut single I Need a Man hit number one on the Billboard dance chart, consolidating her popularity on the gay scene in the process.

However, Jones’s disco-diva phase drew to a natural close as the genre’s popularity began to diminish. After 1979’s Muse album sold poorly, Island Records founder Chris Blackwell encouraged Jones to radically reinvent her sound to reflect her forceful personality and diverse musical influences. At Compass Point Studios in Nassau, Bahamas, he assembled an innovative, genre-fusing band centred around revered reggae musicians Sly Dunbar and Robbie Shakespeare. “Chris took all my different worlds and stuck them all together to create the Compass Point All Stars – the erotic French side, the acid tripping rock ‘n’ roller, the Jamaican drum and bass, the androgynous android electronics,” Jones recalls in I’ll Never Write my Memoirs.

A unique voice

At the same time, Jones began to really embrace her imposing voice. “After the disco albums, I had decided that I was going to sing in my way, not try and become a conventional pop singer,” she writes in her book. She also says Blackwell “didn’t care that I sounded like a man or an entity”, and acknowledges that her strange vocal technique – “somewhere between half-speaking and half-singing” – perfectly complimented the androgynous visual style she was developing. Warm Leatherette was the first Jones album to have cover art designed by Goude, who would play an integral part in the startling way she presented herself to the world. The cover image shows Jones wearing heavy, almost drag-like makeup and a flattop hairstyle; it’s an early example of what Fairclough calls her ability to “celebrate and subvert conventional notions of the female form”.

In the mid-Eighties, Jones made a shift from music to movie stardom with films like A View to a Kill (Credit: Alamy)

Jones is often referred to as Goude’s ‘muse’, but he should be credited with helping to refine and elevate her aesthetic, not inventing it in the first place. Recalling Jones’s performance at a New York gay club in 1977, three years before Warm Leatherette, music critic Barry Walters wrote in 2015: “She was as queer as a relatively straight person could get. Her image celebrated blackness and subverted gender norms; she presented something we had never seen before in pop performance – a woman who was lithe, sexy, and hyperfeminine while also exuding a ribald, butch swagger.” More than 40 years later, Dolly Bing Bing says Jones still inspires the way she presents herself because “my muscles make me look androgynous and yet I play with my female sexuality” – a paradox Jones ushered into the mainstream.

As Dijon points out, Jones was always a true original who used her distinctive image to enrich her equally distinctive music. Walking in the Rain, a song by Australian new wave band Flash in the Pan, which she covered on 1981’s Nightclubbing album, her follow-up to Warm Leatherette, almost sounds like a manifesto for Jones. “Feeling like a woman, looking like a man, sounding like a no-no, mating when I can,” she sings with a cool, confident ennui. “This tune was a game-changer – she said it loud and clear about her presentation and it was animalistic and sexual and self-aware,” Dijon says, adding: “It made me feel free to be myself in all of its complex dimensions – she gave me joy and hope.”

Cleverly chosen cover versions were as integral to the success of Warm Leatherette and Nightclubbing as Jones’s new, genre-fusing sound and unapologetic singing technique. Instead of suggesting show tunes like Send in the Clowns and Tomorrow, which she recorded during her disco phase, Blackwell encouraged Jones to put her own stamp on “unusual pop” songs by Roxy Music (Love Is the Drug), Iggy Pop (Nightclubbing) and Joy Division (She’s Lost Control). The results had the dramatic, avant-garde edge of her image. “When I sing a song I need to get into character, because it is all theatre to me,” Jones writes in I’ll Never Write my Memoirs, where she also admits that she can’t listen to her version of She’s Lost Control because she interpreted it literally and “lost control to such an extent I scared myself”.

During this period, Jones also began to hone her songwriting skills. Released as Nightclubbing’s third single, the self-penned Pull Up to the Bumper pivots on a double entendre that perhaps only Jones could pull off – in 2008, she said coyly that it wasn’t “necessarily” about anal sex. Either way, it’s become one of her signature songs and a staple of her fabulous live shows. Jones then co-wrote all but one song on 1982’s Living My Life, the final album she made at Compass Point Studios. Standout tracks include My Jamaican Guy, which Jones sings largely in Jamaican Patois, and Nipple to the Bottle, which offers a bracingly honest account of breastfeeding and motherhood. “When you don’t get what you want, you scream and you shout, you’re still a baby,” Jones sings witheringly.

Jones continues to serve up brilliant live shows, though her last album was 2008’s Hurricane (Credit: Getty Images)

After Living My Life, Jones cemented her status as an ’80s pop culture icon by transitioning into acting with roles opposite Arnold Schwarzenegger in 1984’s Conan the Destroyer and Roger Moore in the 1985 Bond film A View to a Kill. That year, she also scored one of her biggest hits with Slave to the Rhythm, a bombastic dance song produced by Frankie Goes to Hollywood collaborator Trevor Horn. By this point, she’d definitely earned the famous grand introduction afforded to her on the song by actor Ian McShane: “Ladies and Gentlemen… Miss Grace Jones.”

Her subsequent musical output has been sparing, but often very impressive. Jones’s most recent album, 2008’s Hurricane, features what could be her most affecting song: Williams’ Blood. On this gospel-flecked ballad, Jones explores the dichotomy between her family’s religious beliefs – her father Robert was a Pentecostal minister – and her own rebellious nature, by aligning with her paternal grandfather, a musician who “womanised” as he “went from town to town” touring with Nat King Cole. Together with the 2015 book I’ll Never Write My Memoirs and Sophie Fiennes’s 2017 documentary Bloodlight and Bami, it shows a more human side to Jones – who was famously presented as a cyborg-like racer in a car advert directed by Goude. In Fiennes’s film, she says she developed her formidable side by imitating her disciplinarian step-grandfather, saying: “That’s why I’m scary. That’s the male dominant scary person I become.”

Then again, Jones seems to know never to give too much away because a certain amount of enigma enhances her appeal. Forty years after she released her first great album, Warm Leatherette, she remains as impossible to pigeonhole as the music which Dijon describes as a mix of “reggae, dub, disco, French ballads, rock, punk and rap”, while the advice she dishes out on the album’s biggest single – “Your private life drama, baby, leave it out” – is something she herself pays heed to. Jones’s own private life drama is for her alone to navigate; she’ll let us in only as much as she wants to.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.