When Gabrielle Diamond and her boyfriend, Brian Cox, showed up for eviction court on October 15, they were more than a little nervous.

The two had been renting a bedroom in transitional housing for veterans in Kansas City, Missouri, since January, paying $600 per month for their month-to-month lease. Almost as soon as they moved in, Diamond says, the issues started. The building was unclean and attracted mice, and the landlord would make unannounced weekly visits; at one point, the couple were asked to move out temporarily for house repairs without any assistance, financial or otherwise.

Then, this summer, they received a letter requesting that they move out in 30 days. But because of what they said were errors in the document, they continued to pay their rent and refused to leave. In September, their landlord escalated the issue, and they were served with court papers alleging they were in breach of their lease, and responsible for the uncleanliness and other damage. October 15 would be their first court hearing, and because of the pandemic, they were told to appear via video conference.

With the house’s poor internet service, which was so slow that Diamond jokingly referred to it as “McDonald’s Wi-Fi,” and their unfamiliarity with the Webex software they were told to use, it took them a few attempts to download the software and access the meeting.

Beyond the technical difficulties, though, Diamond was also afraid that a video conference meant she wouldn’t “be able to get out what I needed to get out,” she says. It would be much easier to express herself in person than when she was “talking to a piece of metal.”

Luckily, the conference ended abruptly after just 10 minutes—before they could appear. All of the day’s dockets were canceled, giving them a brief reprieve until their rescheduled hearing date in December.

Diamond and Cox are far from alone. The pandemic means that across America, eviction hearings that used to be handled only in physical courtrooms are now also taking place over video, or simply by phone conference. The result, say lawyers and tenants’ rights activists, is that an already problematic situation has become dramatically, tragically worse.

An unprecedented, imperfect moratorium

Before the pandemic, an average of 3.6 million Americans lost their homes to evictions every year, according to Princeton University’s Eviction Lab. By the end of 2020, this number could increase exponentially, with one report from the Aspen Institute estimating that, without further federal aid, between 30 to 40 million people may be at risk of eviction in the next several months. The financial hardship exacerbated by covid-19 has left many in a precarious situation.

In theory, this should not be the case. Earlier this year, the CARES Act provided some relief to tenants in properties backed by federal mortgages, by introducing a 120-day moratorium that made it illegal to evict people or charge them late fees for non-payment of rent. But this expired on July 24, and evictions, which were temporarily curbed, began restarting across the country.

On September 4, the CDC enacted another eviction moratorium by expanding protection to all renters facing financial hardship, not just those where mortgages were federally backed. “Housing stability helps protect public health,” the agency wrote. Evictions encouraged the spread of covid-19 by forcing people into homeless shelters where social distancing was hard, and increased the likelihood of severe illness.

In reality, however, the CDC protections were full of holes. They only protected evictions for people who were unable to pay their rent—and only then if tenants filed a formal declaration stating the pandemic’s financial impact on them. There were carve-outs for landlords, who were not required to inform the tenants they sought to evict about CDC protections, and could continue to accrue unpaid rent, due at the end of the moratorium. They could even start court proceedings as long as the actual, physical removal did not take place before January 1. They also allowed landlords to evict tenants for non-financial reasons: creating nuisances, breaching their leases, or a lease period ending. Such was the case with Diamond and Cox, who were accused of breaching their lease and told by their landlord that their month-to-month contract would not be renewed.

As a result, eviction courts are continuing across the country. In every state except Hawaii and Nebraska, they are now either allowed, required, or encouraged to be conducted by videoconference or phone dial-in.

National level data is not available, because there is no federal agency that tracks evictions across the state, Eviction Lab’s database, which monitors 26 cities, including Kansas City, has tracked nearly 115,000 evictions filed since the beginning of the pandemic. The nationwide figure—accounting for cities not on the list—is much higher. And then there are an unknown number of extra-legal evictions, where landlords simply intimidate, harass, or otherwise make living conditions unbearable for tenants until they leave.

While remote proceedings are meant to limit the spread of covid-19 in courtrooms, tenants’ rights advocates say that they do little to ensure due process during the hearings—and in fact make things worse by forcing people out of their homes and into unsafe situations.

“It’s a totally untenable situation,” says Lee Camp, a senior attorney with Arch City Defenders, a legal aid organization in St. Louis. “Appear by phone [or video] and have your due process rights violated, or go and risk your life.”

“A disadvantage to appear virtually”

Legal aid organizations across the country say they have observed worrying practices in remote hearings.

First, there is the lack of consistency. Housing courts across the country use a patchwork of services, including Webex, Zoom, BlueJeans, and others. In some places, like St. Louis, which has both city and county courts, the situation is split: one court uses Zoom and the other Webex. On top of this, some courts are fully virtual while others are hybrid, and others switch between virtual, hybrid, and in-person—sometimes during the same cases. This leads to many opportunities for confusion: Diamond, for example, says that she was required to appear in person for her second hearing, but the one after that is scheduled for Webex.)

On top of this, notifications from Zoom or Webex can get lost in spam, leading to tenants missing court appearances and, in some cases, receiving default eviction judgments as a result.

Then there is the question of access. With so many services closed, including the libraries and schools that might provide free WiFi, some defendants have been unable to access the meetings at all. Others have had difficulties submitting documents either in person or via web upload.

Tenants with disabilities, like hearing loss, or those who require translation help, are limited even further. Camp says he was horrified by one case during which a tenant who was being evicted over a video conference had to rely on the same property manager evicting him to translate for the court. If the hearing was held in person, Camp says, the court would have been required to provide translation services.

Valerie Hartman, a public information officer for Jackson County’s 16th Circuit Court, which is not where the incident Camp described occurred, says that her court has made a number of accommodations for people with disabilities and provide interpreter’s services when requested. “All parties always have the option of reaching out to the judge to request that their hearing be held in person rather than virtually,” she says.

Studies from immigration courts, some of which have been virtual since 1996, have shown worse outcomes for defendants appearing by video. The most comprehensive study, from 2015, found that detained individuals were more likely to be deported over video conference than in person. Meanwhile, a survey of immigration judges found that half of them had changed evaluations of whether testimony was credible made during a video hearing after holding an in-person hearing.

Evidence from criminal proceedings support this. One study of criminal bail hearings found that defendants who appeared by video had bonds set up to 90% higher than similar defendants appearing in-person.

“There’s a fair question as to whether Zoom eviction hearings really provide the meaningful opportunity to be heard.”

Douglas Keith, Brennan Center for Justice

Advocates say that these determinations are just as important in housing court.

Douglas Keith, an attorney with the Brennan Center for Justice’s Democracy Program says that many protections the courts are supposed to provide are harder to achieve virtually.

“There is a right to due process, a right for a meaningful opportunity to be heard,” Keith says. “There’s a fair question as to whether Zoom eviction hearings really provide the meaningful opportunity to be heard.”

But as bad as video evictions are, advocates say that appearing by phone is even worse.

Dial-in conferences can be garbled or cut out, making it difficult for defendants representing themselves to advocate or even fully understand the proceedings.

This is worse if the defendant is the only one calling in, while others are on video or meeting in person. Camp, of Arch City Defenders, explains: “The judge is on screen. The attorney for their landlord is on the screen. They’re having a conversation, somewhat face to face, at least virtually. And the tenant is sitting here on the phone, not able to see what’s happening, not able to review anything that would be offered by the court.”

And that assumes that the phone line is clear.

Some judges recognize the challenges of call-in appearances. During a recent hearing in Jackson County, one judge advised a defendant, “it’s hard … to see documents on the phone, so I would recommend, if you can, to come in person.”

“I’m well aware that covid numbers are going up in Kansas City,” the judge added, but “it may put you at a disadvantage to appear virtually.”

But other judges only provide phone conference lines. If any wants to hold a videoconference, the requesting party must set up the call with their own account.

“Eviction proceedings were a farce”

When the wave of evictions hits in January and February, after the CDC moratorium expires, the displacement will not affect all Americans equally. Just as the pandemic has disproportionately sickened and killed people of color, one study in Missouri’s Jackson County, which includes most of Kansas City, found that Black individuals are far more likely to be evicted than their white counterparts, even when accounting for income.

Many of the evictions taking place will go through housing courts, which have historically had dismal outcomes for defendants. One analysis of all evictions filed in 2017, conducted by the Kansas City Eviction Project (which is affiliated with KC Tenants), showed landlords winning 99.7% of cases that made it to judgment. Tenants won in only 18 of those cases.

The difference in legal outcomes may be partially attributable to the vast disparity in representation. That same court data showed that 84% of landlords had lawyers, while only 1.3% of tenants had legal representation.

The group’s data showed that tenants didn’t appear in 48% of cases. Some of these were deliberate choices.

“The eviction proceedings were a farce, and the tenants knew it,” says John Pollock, coordinator of the National Coalition for a Civil Right to Counsel. “There was very little reason for them to participate, so they didn’t.”

For others, it was simply that the burden of appearing in court was too high.

“For some litigants, the courthouse is an hour bus ride away or they lack access to childcare or time off work that would enable appearance,” explains Emily Benfer, a visiting professor at Wake Forest University and one of the creators of Eviction Lab’s COVID-19 Housing Policy Scorecard. (The scorecard gave Missouri a 0/5 rating.)

“The eviction proceedings were a farce, and tenants knew it. There was very little reason for them to participate, so they didn’t.”

John Pollock, National Coalition for a Civil Right to Counsel

In theory, Benfer adds, moving housing court to a virtual format could make it easier. “If additional supports to increase accessibility of remote hearings were put in place, remote hearings could increase appearance rates and decrease default judgements.”

And court representatives and legal aid attorneys alike point to anecdotal evidence suggesting that defendants are appearing more frequently.

Hartman, from Jackson County’s 16th Circuit Court, says that while they don’t have concrete data, “our impression is that more defendants are appearing for the landlord tenant docket now that they have the option of appearing by phone, WebEx, or in person.”

But that’s the wrong metric, says Pollock. “Whether someone shows up as the metric of whether or not things are working, that’s not justice. That’s an empty gesture,” he says. “If everyone shows up and exactly the same thing happens, it makes you wonder what the point of this system is.”

Video-bombing the courts

When Gabrielle Diamond and Brian Cox had their hearing postponed, it wasn’t because of a missing notification or a technical glitch. It was the result of a direct intervention: videobombing.

She and her boyfriend had been logged into the meeting room for less than 10 minutes when activists dialed in and took it over. In some cases, they had gained access by pretending to be tenants with scheduled hearings.

“No one should be evicted during a pandemic,” one said. “This is not justice. This is not due process. This is violence. All evictions must end. People are dying.”

The speech came out in bits and pieces, with the judge muting each speaker’s line before another activist would jump in, continuing where his/her predecessor was cut off:

“Tenants on the line, this is not your fault. You deserve a decent home. You deserve shelter during the pandemic. You are not alone. KC Tenants has your back. Judge, you are complicit with every eviction that you hear. You are making people homeless during a pandemic. You are killing people. It does not have to be this way. You have a choice. End evictions. People are dying.”

Diamond and Cox were on mute, but “we were cheering,” she recalls.

“Like, ‘Yes! Someone has our back!’ ”

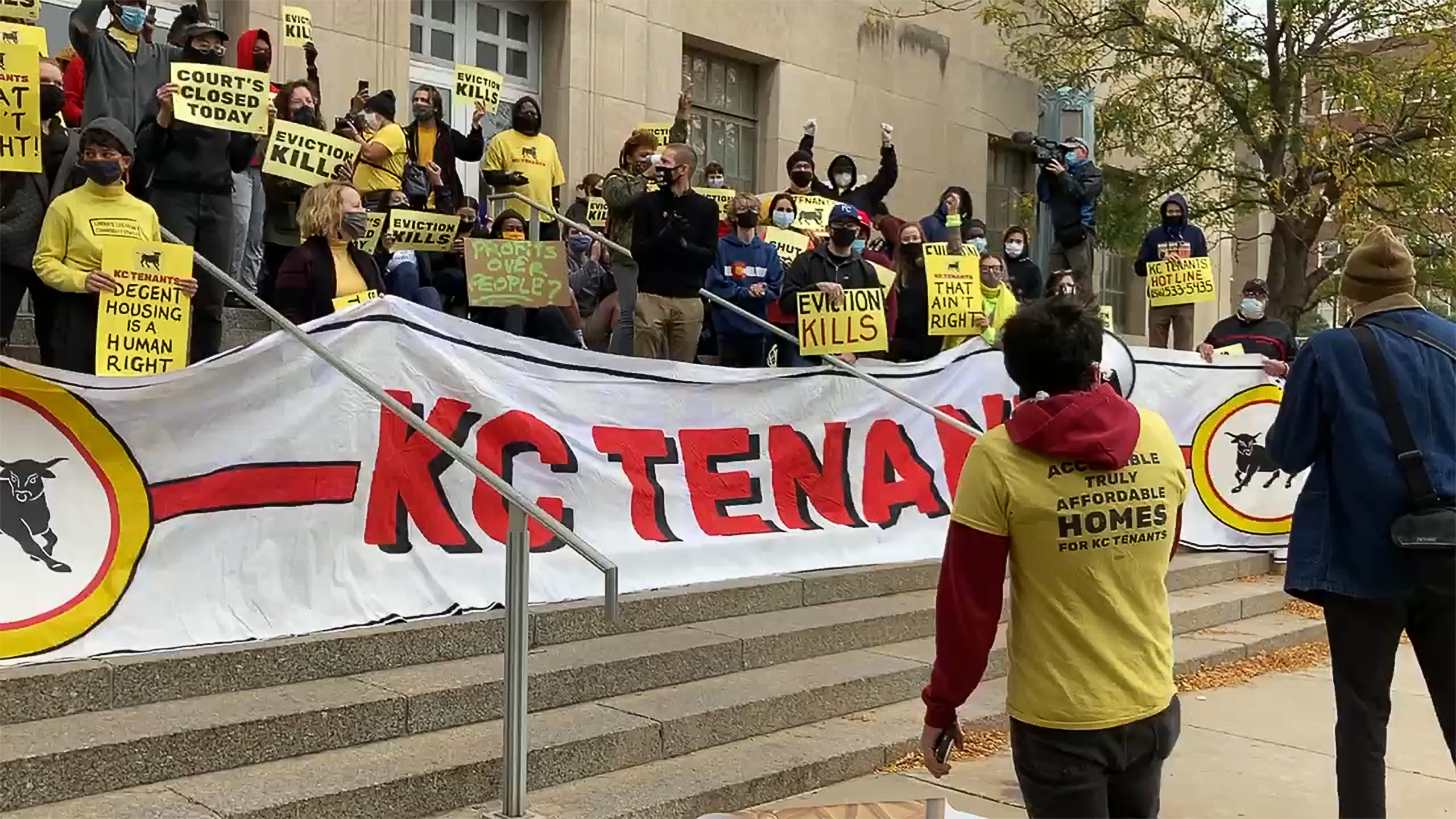

By their own count, KC Tenants has disrupted 138 evictions in October and 155 in November, including all of the dockets scheduled on the day that Diamond and her boyfriend were to appear, giving beleaguered tenants a little more time to remain in their homes and come up with a plan.

The group is also taking more traditional routes to protect tenants: With the help of the ACLU, KC Tenants has filed a lawsuit against the Jackson County Circuit Court for allowing evictions to continue in defiance of the CDC moratorium. (In late November, a federal judge denied their request for a preliminary injunction on eviction proceedings.) But video bombing has been an effective stall tactic.

“Every single eviction is an act of violence,” says Tara Raghuveer, the organization’s founding director. “With every eviction that we allow right now, we’re prioritizing a landlord’s profit over a tenant’s life, period.”

As a result of KC Tenants’ efforts, at least one Jackson County judge overseeing housing courts has moved all of her remaining cases to in-person only, which Raghuveer says is another step in ending evictions completely.

Meanwhile, other attorneys and advocates say that, if remote evictions must continue—and most agree that they should not—they should be redesigned with tenants’ needs first. Keith, from the Brennan Center, says that the focus should be on “ensuring that they [eviction hearings] are fair at their core, and that courts are not prioritizing efficiency over fairness.”

That requires reorienting how courts think about adopting new technologies to focus on how “unrepresented people are able to navigate these newly created systems, not how attorneys are able to do so,” he adds.

Camp, meanwhile, wonders whether the technology companies could be held accountable. “Did they ever think that their platform could be used to carry out courtroom business, particularly something as dangerous as evictions at this moment?”

Private companies have taken political and social stances. Cisco, the parent company of Webex, is especially proud of its reputation for corporate social responsibility: its CEO, Chuck Robbins, has spoken out against the family separation policy, and has committed $50 million to help end homelessness in Santa Clara County, where the company is based.

In an emailed statement, a company representative said, “Cisco Webex helps facilitate secure, reliable communication for people regardless of where they may be. If our customers have users who require support to use our products, we are committed to providing it.”

He did not respond to a specific question on whether the company saw a conflict between the use of its platform in contributing to homelessness and its commitment to ending homelessness in its own backyard, but said “we recognize we have an opportunity and responsibility to support the most vulnerable among us. We have made financial and technology commitments to nonprofit organizations that are focused on meaningful change and recently increased that support to help at-risk individuals and families, given the ongoing crisis.”

For Pollock, the accessibility issues presented by Webex, Zoom, and other conferencing platforms could be resolved if all tenants had access to legal representation. “Attorneys have the knowledge and experience with eviction proceedings, and are comfortable enough with the technology,” he says.

But only a few cities and states have passed bills guaranteeing counsel in civil cases, and in the meantime, there is no national relief on the horizon. At the federal level, there have yet to be any serious proposals to either expand the CDC moratoria or pass another stimulus package with broader rental assistance.

“We’ve done nothing but kick the can down the road,” says Camp. And without significant federal financial support, he adds, come January and February, “a house of cards … will begin to fall.”

Others worry that courts will continue the use of video after the pandemic, without challenge or scrutiny.

There was this understanding, says Keith, of the Brennan Center, early on in the pandemic that “the courts [were] trying to figure it out, build this place as they’re flying,” but now, he adds, it’s “no longer … an emergency situation,” and courts should no longer get that same benefit of the doubt.

Gabrielle Diamond and her partner have more immediate concerns, however. When they return to the housing court, their hearing will once again be held by Webex. This time, at least, they’ll be represented by counsel. She dreams of the day that this will all be over: “I just want us to have our own apartment, with decent jobs, not having to worry about all the stressful things of evictions.”