The theatrical life and death 50 years ago of one of Japan’s most celebrated and controversial authors created an enduring – but troubling myth, writes Thomas Graham.

S

Standing on a balcony, as if on stage, the small, immaculate figure appeals to the army assembled below. The figure is Yukio Mishima, real name Kimitake Hiraoka. He was Japan’s most famous living novelist when, on 25 November 1970, he went to an army base in Tokyo, kidnapped the commander, had him assemble the garrison, then tried to start a coup. He railed against the US-backed state and constitution, berated the soldiers for their submissiveness and challenged them to return the Emperor to his pre-war position as living god and national leader. The audience, at first politely quiet, or just stunned into silence, soon drowned him out with jeers. Mishima stepped back inside and said: “I don’t think they heard me.” Then he knelt down and killed himself by seppuku, the Samurai’s ritual suicide.

More like this:

– The mysterious appeal of the labyrinth

– Why don’t we appreciate funny writing?

Mishima’s death shocked the Japanese public. He was a literary celebrity, a macho and provocative but also rather ridiculous character, perhaps akin to Norman Mailer in the US, or Michel Houellebecq in today’s France. But what had seemed to be posturing had suddenly become very real. It was the morning of the opening of the 64th session of the Diet, Japan’s parliament, and the Emperor himself was present. The prime minister’s speech on the government agenda for the coming year was somewhat overshadowed. No one had died by seppuku since the last days of World War Two.

This photograph – taken a few days before his death – shows Mishima with his loyal cadets (Credit: Getty Images)

“Some thought he had gone mad, others that this was the last in a series of exhibitionistic acts, one more expression of the desire to shock for which he had become notorious,” wrote the Japanese philosopher Hide Ishiguro in a 1975 essay for The New York Review. “A few people on the political right saw his death as a patriotic gesture of protest against present-day Japan. Others believed that it was a despairing, gruesome farce contrived by a talented man who had been an enfant terrible and who could not bear to live on into middle age and mediocrity.” For his part, Mishima once told his wife that “even if I am not immediately understood, it’s OK, because I’ll be understood by the Japan of 50 or 100 years’ time.”

In 1949, Mishima arrived on Japan’s literary scene with Confessions of a Mask, a kind of autobiography, thinly veiled as a novel, that made him famous in his early twenties. It tells the story of a delicate, sensitive boy who is all but held captive by his grandmother. She is ill and he is made to nurse her. Rather than playing outside with other boys, he is confined with her for years in the sickly-sweet smelling darkness of her bedroom.

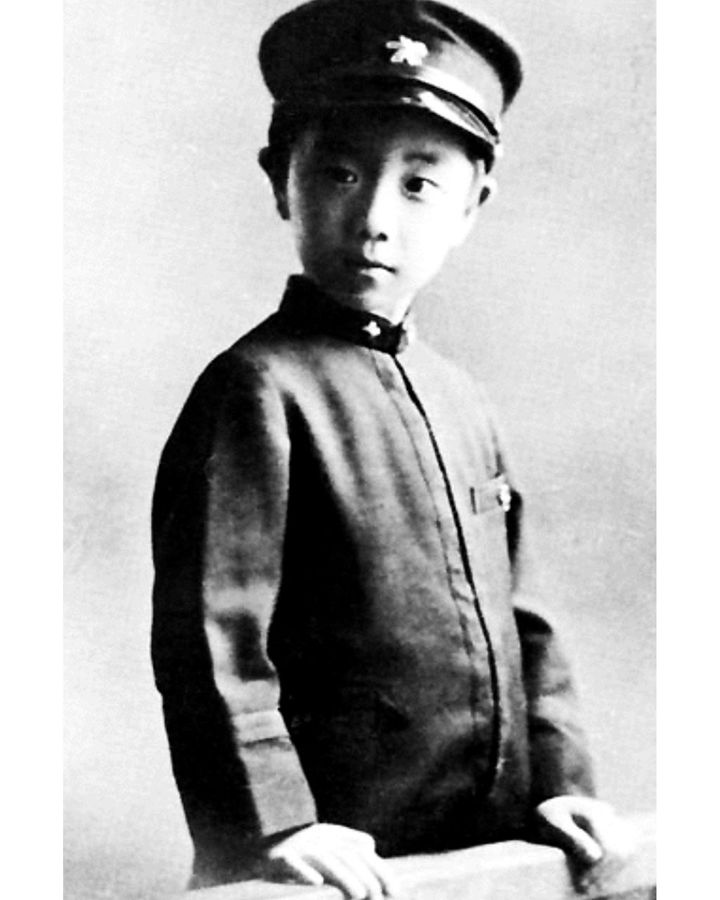

Mishima spent part of his childhood living with his grandmother – an experience that he immortalised in the 1949 novel Confessions of a Mask (Credit: Alamy)

The boy’s mind develops in that room. Fantasy and reality are never quite separated; fantasy, the stronger twin, grows dominant. By the time the grandmother dies and the boy emerges, he has developed a fixation with roleplaying, with life as theatre. He cannot resist layering fantasies over life around him. Men and boys, especially muscular, straightforward ones, are assigned roles in his vivid, often violent daydreams. Meanwhile he obsesses over his own deviance and appearing normal. He learns how to play his own role: “The reluctant masquerade had begun.”

Beauty and destruction

Confessions of a Mask continues up to the end of the boy’s adolescence, detailing the entwined evolution of his internal and external lives and his homosexual awakening. In many ways, it is the key to understanding Mishima’s later life and works. It reveals the roots of the aesthetic sensibility, so tied to his sexuality, which proved to be Mishima’s steering obsession. The narrator writes that he “sensuously accepted the creed of death that was popular during the war”, when conscription and self-sacrifice seemed certain and imminent, and indeed Mishima was forever fixated on the idea that beauty is most beautiful when it is transient – and above all on the cusp of destruction. This creed mingles with admiration for the male form, a form the frail narrator lacks, to produce fantasies of brave warriors and their bloody demises. This private world of “Night and Blood and Death” was filled with the “most sophisticated of cruelties and the most exquisite of crimes”, all recounted with a cool detachment.

But then Confessions of a Mask also suggests the slippery interplay between performance and reality that characterised everything Mishima did and wrote. It gave the impression of revealing the author locked in some dark struggle with himself – while also suggesting it may just be a masterful manipulation of media and publicity. Mishima had it both ways, scandalising society while retaining a wisp of deniability.

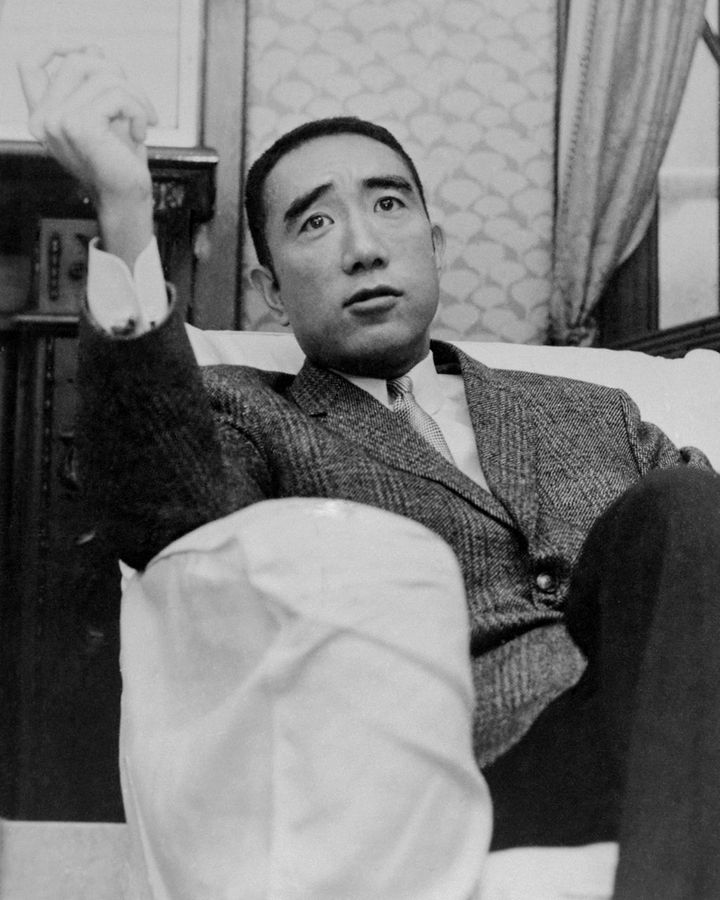

Mishima was strongly influenced by European culture and philosophy, including Nietzsche and the late Romantics (Credit: Getty Images)

The formula worked. It turned Mishima into the enfant terrible of postwar Japanese literature and won him a broad readership at home. He was, though decadent, a disciplined and prolific writer, churning out reams of popular fiction alongside high literature and dozens of Noh plays. He worked himself into Tokyo high society with the same focus, cultivating a dandyish image. His face, with its rugged bones and soft eyes, photographed well. And he was a friend to foreign bureaux and their correspondents, ingratiating himself and doing what he could to extend his celebrity across the Pacific – with some success. “If Sony’s Akio Morita was the most famous Japanese abroad,” wrote John Nathan, a translator and later a biographer of Mishima’s, “Mishima ran a close second.”

Mishima’s novels during the 50s mostly mined the same suggestively autobiographical vein as Confessions of a Mask. In Forbidden Colours (1951), an ageing writer manipulates a young gay man who has become engaged for convenience and financial security. In Temple of the Golden Pavilion (1956), an acolyte at the temple is transfixed by its beauty in the belief that it will be destroyed by the bombing raids – and when it survives the war, he takes it on himself to destroy it. And in Kyoko’s House (1959), a boxer takes up right-wing politics, while an actor becomes involved in a sado-masochistic sexual relationship that ends in a double suicide.

Mishima’s subject matter was his own, but in style, at least, he was held to be a protege of the Nobel-prize winner Yasunari Kawabata, who saw the function of literature as artistic, not propagandistic. Much of Mishima’s writing seems to cleave to this belief absolutely, with its formal, almost traditional style focusing on intensely sensual description above all else. Turned to bodies, clothes and scent, this selective depiction is almost fetishistic. “The shocking embrace of sheer nylon and the imitation damask of the couch gave the room a sense of agitation… The sharp hiss of the sash unwinding, like a serpent’s warning, was followed by a softer swishing sound as the kimono slipped to the floor.” (From The Sailor Who Fell From Grace with the Sea, 1963)

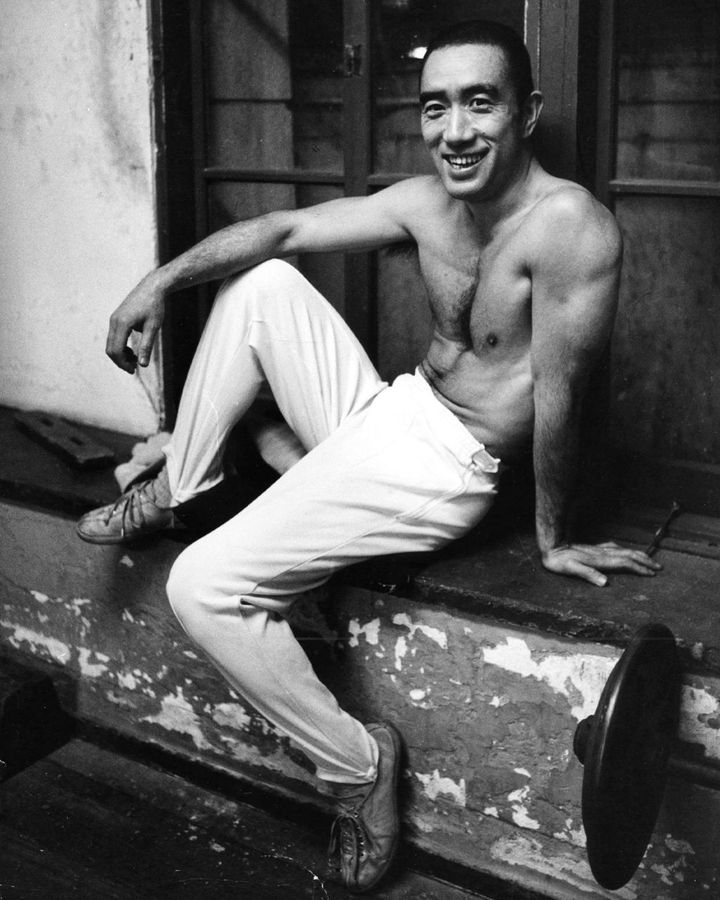

But then something changed, and in the 60s the political phase of Mishima’s life might be said to begin. Having portrayed himself as a pure aesthete, a decadent romantic, in the last 10 years of his life Mishima underwent a transformation. It was then that he took up bodybuilding, working out in the gym for two hours a day to add muscle to his frail, 5ft-3in frame. He began bronzing himself in the sun, too, and set up a group of right-wing male university students that he led through workout routines. The stated purpose of this Shield Society was to assist the army in the event of a communist revolution.

In his later years, Mishima took up bodybuilding to add bulk to his frail physique (Credit: Getty Images)

Behind this transformation was a rationale which was, if not distilled, at least accumulated in Sun and Steel” Art, Action and Ritual Death, an enigmatic essay published in 1968, two years before his death. Looking back, he saw that he had been corroded and weakened by an excess of fantasy and words, and a paucity of materiality and action. “In the average person, I imagine, the body precedes language,” Mishima writes. “In my case, words came first of all; then – belatedly, with every appearance of extreme reluctance, and already clothed in concepts – came the flesh. It was already, as goes without saying, sadly wasted by words.” He sought to rebalance himself and revived an old Samurai concept, the “harmony of pen and sword”. He longed to be seen as, to become, a “man of action”.

A final burst of creativity

Mishima was by now in his forties and acutely aware of his age. “The beautiful should die young, and everyone else should live as long as possible,” he wrote, in a piece on the early death of the actor James Dean. “Unfortunately, 95% of people get it backwards, with gorgeous people lingering into their eighties and hideous fools dropping dead at 21.” Mishima felt his moment was passing and began plotting his final act.

Everyone, at some point, sees life as a stage. But few live and choreograph their lives as theatre, and fewer still would use seppuku to close out their performance. For Mishima, though, it was the culmination of a lifelong fantasy. The elements had been there from the very start, in Confessions of a Mask: soldiers, death and blood. The self-transformation into a warrior had made him into the object of his desire: something beautiful, something worth destroying. And the fixation on seppuku had grown in plain sight. Mishima even wrote and starred in a short film, Patriotism, in which he acted it out in detail. Perhaps Mishima’s final act was a political protest, too – but it was certainly death as art.

On 25 November 1970, Mishima gave a speech to the army assembled below him, before taking his own life (Credit: Getty Images)

On the morning of his last day, Mishima posted the final book of his tetralogy, The Sea of Fertility, to his publisher. These four books, written in a frantic burst of creativity, were something new. Starting in 1912, shortly after the Russo-Japanese War, and ending in 1975, they span a period of extraordinary change: from the ascendance of the Imperial Japan, through the annihilation of World War Two, and to the emergence of a capitalist, consumerist Japan. They are held together by one character, Honda – perhaps a stand-in for Mishima – and the repeated reincarnation of his boyhood friend, an enduring soul surrounded by change and decline.

Compared to Mishima’s early works, The Sea of Fertility contains much dense philosophising. And, after the second, the volumes feel rushed, becoming increasingly slim. Mishima wrote most of the final volume, The Decay of the Angel, during a seaside family holiday in August 1970. In a letter dated 18 November, 1970, to a mentor of his, Fumio Kiyomizu, Mishima wrote, “To me, finishing this [book] is nothing more than the end of the world.” The last lines of The Decay of the Angel are very still.

“It was a bright, quiet garden, without striking features. Like a rosary rubbed between the hands, the shrilling of cicadas held sway.

There was no other sound. The garden was empty. He had come, thought Honda, to a place that had no memories, nothing.

The noontide sun of summer flowed over the still garden.”

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.