The Cascade volcanoes that run from northern California to southern British Columbia aren’t exactly the most active volcanoes on Earth. While other places like Kamchatka in Russia and Indonesia tend to have multiple volcanoes erupting each day, only two volcanoes have erupted in the Cascades since 1900: Mount St. Helens in Washington and Lassen Peak in California.

Yet, for a volcanic arc like the Cascades, 120 years is nothing. In order to really understand what is happening in such a place, we need to look at longer timescales because the geologic processes of the Cascades work on deep time.

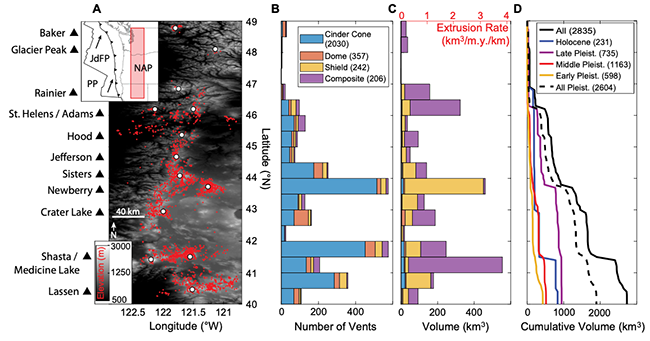

A new study in Geology by University of Oregon graduate student Daniel O’Hara and colleagues tries to do just that. They set out to examine the long history of Cascade volcanoes and really count the number of volcanic vents from north to south. They also compiled the volumes of stuff that has erupted along that stretch as well over the last 2.6 million years (also know as the Quaternary Period). What they found was two places really dominate the eruptions of the Cascades, and they are both changing in different ways.

In the study, O’Hara and his co-workers, University of Oregon professor Leif Karlstrom and USGS geologist David Ramsey, used existing data that could be used to identify the locations and ages of volcanoes all along the Cascades. They started by examining over 2,100 separate volcanoes, some massive composite volcanoes like Mount Shasta and some tiny cinder cones. They found that when you add up all the volume of these volcanic features, you get ~650 cubic miles (2,730 cubic kilometers) of stuff erupted from the Cascades over the last 2.6 million years.

So, how much is that? It works out to be, on average, about 0.4 cubic miles per mile of Cascades per million years (or 1.05 cubic kilometers per kilometer per million years). In other words, every mile from the Washington border with Canada to Lassen in northern California produced enough material to cover all of Manhattan 92 feet deep every million years. That’s pretty good! And that’s only the preserved parts. Some estimates put the total erupted volume at over 1,500 cubic miles (6,400 cubic kilometers), if you count all the eroded material and ash that drifted away during eruptions.

The vent numbers and volumes erupted from the Cascades, from O’Hara and others (2020). Credit: Geology.

It isn’t evenly distributed, though. There are places along the Cascades where there are more eruptions. O’Hara and colleagues identified two places where eruptions have piled up more stuff: central Oregon around Three Sisters and Newberry, and northern California around Mount Shasta and Medicine Lake. Each of these areas have erupted over 100 cubic miles (400 cubic kilometers) alone.

Yet, they aren’t erupting it the same way. In the Oregon Cascades, the volume of erupted material is dominated by shield volcanoes such as Newberry. It is also a place where there are hundreds of tiny cinder cone volcanoes as well.

Compare that with northern California, where the beast of Mount Shasta dominates the volume of volcanic material. There are still lots of cinder cones, though, which seem to be a hallmark of Cascade volcanism.

Three Sisters in Oregon. Credit: USGS

This has changed over time as well. In the most recent 10,000 years (the Holocene), we’ve seen the most eruptions by volume in northern California, accounting for close to half of the nearly 250 cubic miles of erupted material identified in O’Hara’s study. On the other hand, if you look back at ~11,000 to 129,000 years ago, it is the central Oregon Cascades that contribute the most.

The other trait that O’Hara and his colleagues identified was whether each area had a more focused location for eruptions or a more distributed. This more or less means that a focused location might be a single volcano or cluster of volcanoes while distributed suggests lots of smaller vents over a wide area.

It turns out that Northern California seems to be trending toward a more focused pattern, all coalescing around Mount Shasta. On the other hand, central Oregon is going the other way, trending toward more distributed locations. I think it is anyone’s guess why that is, but it is an interesting observatory of how volcanic areas might change over time.

In all, O’Hara study adds some more context to the story of the Cascades. Even though we can be lulled into a sense of complacency about the Cascade volcanoes, they have been active for millions of years and will continue to be so. Now we have a better picture of just have the activity is spread over time and space.