Laser ranging only gives you a location window that’s up to several thousand kilometers in distance. For better predictions, debris trackers can also measure the reflection of sunlight off these objects, which can be used to narrow those windows to just a few meters. But these sunlight reflections can only be observed around dawn or twilight, when the ground stations are still dark but the satellites themselves are illuminated.

A team of European researchers think they’ve finally gotten around this problem, according to a new paper published in Nature Communications. A team led by Michael Steindorfer, a space debris researcher from the Austrian Academy of Sciences, has figured out a way to visualize space debris during broad daylight against a blue sky background. Instead of measuring sunlight reflections the old fashioned way, the new daylight technique uses a specialized filter, telescope, and camera system to observe stars in the sky during daylight (when they are 10 times harder to spot). This gives you a background that contrasts with the space junk, which reflect light more brightly since they’re closer to Earth, so you no longer have to wait till twilight or pre-dawn to get sunlight reflection measurements. In addition, the team designed new software that automatically corrects object location predictions in real-time more accurately than previous systems.

The team tested out this new “daylight system” during the daytime on four different rocket bodies moving through orbit just under 1,000 kilometers above Earth’s surface, pinpointing their locations down to a range of about one meter or so. They later validated the system through observations of 40 other objects. Altogether, the researchers believe the new daylight system can make a laser ranging system more accurate for between 6 and 22 hours a day, depending on the season. It should be well within the means for a tracking station to set up such a system.

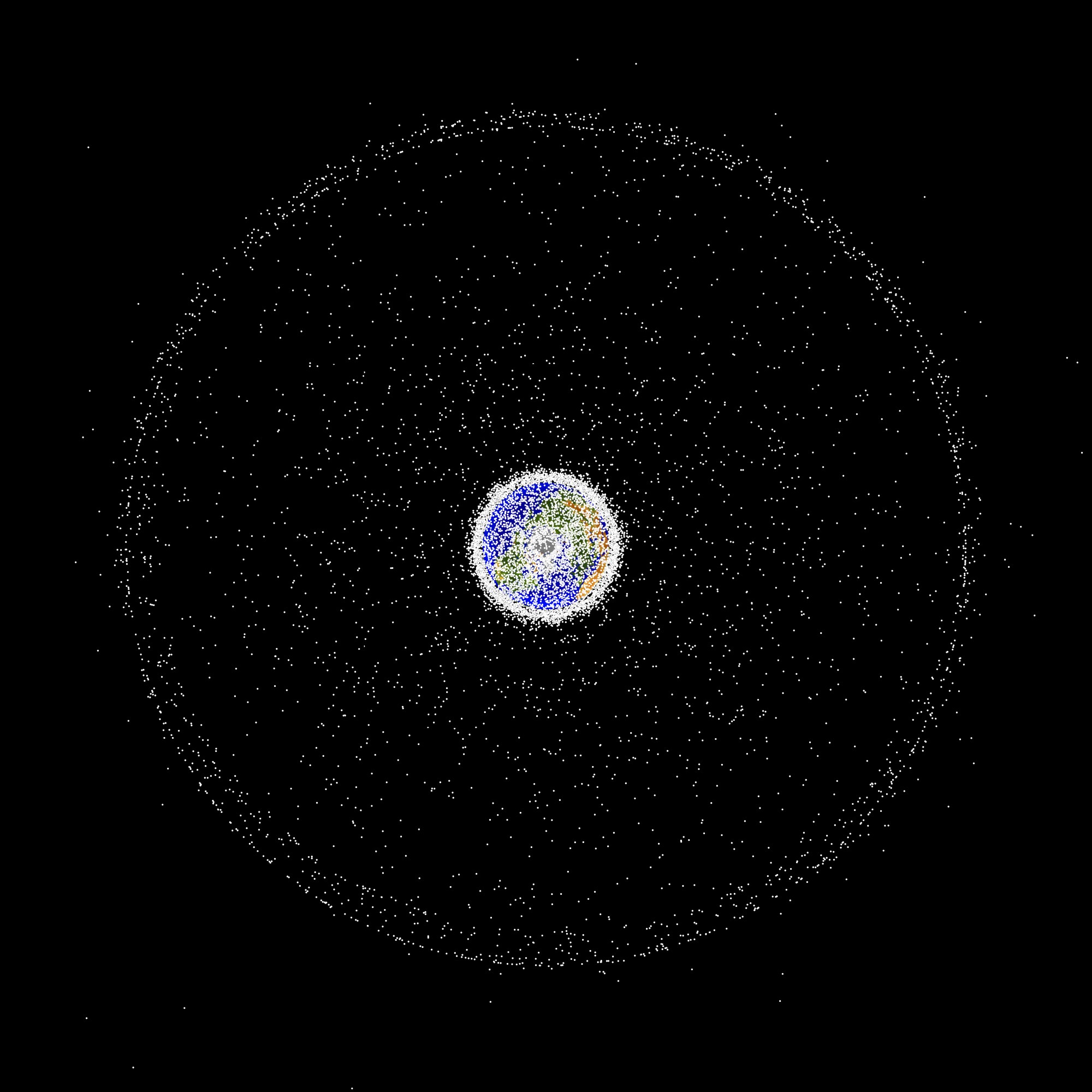

Work in progress

NASA ODPO

Conducting observations in daylight does have its drawbacks, however, and Steindorfer allows that reflections from other objects could easily interfere with debris tracking. Both the hardware and software need to be improved over time to reduce inaccurate predictions, and Steindorfer argues that the whole system needs to be thought of as a continued work in progress. Frueh, who did not work on the new study, also adds that daylight tracking is already possible with radar, and daylight optical observations have also been used to detect the movement of particularly bright debris.

But combining these telescope observations with laser ranging measurements does provide “a significant improvement to the current accuracies of catalogued objects, especially in high altitude orbits, which are not radar tracked,” says Frueh. She cautions it cannot serve as an end-all solution for scanning debris of all sizes and altitudes–but should make for another useful tool in the debris tracking toolbelt.

Steindorfer is naturally more optimistic about the impact of the new daylight system. He believes it could help foster a more organized network of debris tracking stations around the world, working together in a way that “significantly improves orbital predictions and provides better warnings of possible collisions, or even inform future space debris removal missions.” Given how bad the space junk problem is getting, any new solutions are more than welcome at this point.