As soon as we cast our eyes over a scene, we experience it as a full-color vista. The idea that we could look at something and not notice what color it was is a strange one.

But an interesting new study from researchers Michael A. Cohen and Jordan Rubenstein suggests that our vision contains less color information than you’d think.

Cohen and Rubenstein found that a large proportion of people failed to spot that an image contained major color distortions in their peripheral vision.

The participants, all of whom had normal vision, were shown a series of images. Their task was to focus on the center of each picture and look out for a certain feature of the image (either human faces, or indoor vs. outdoor scenes). Each picture was shown for 288 milliseconds.

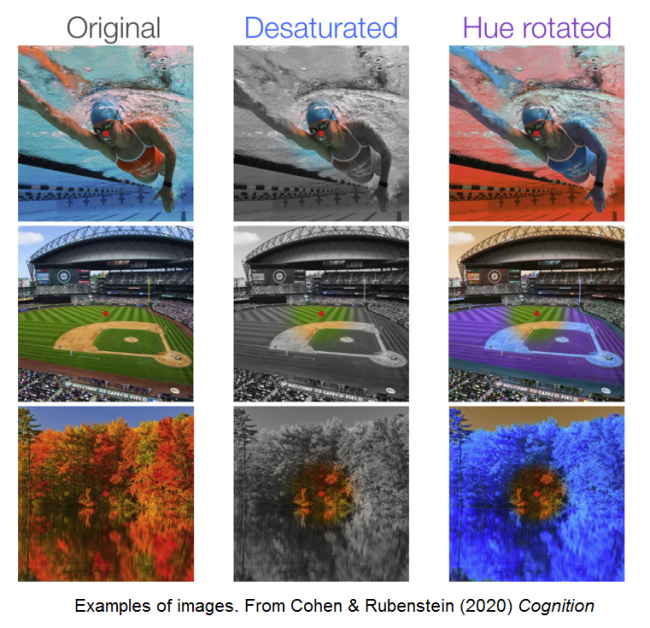

The trick was that the final image in each series was sometimes distorted. Sometimes, the colors were desaturated, leaving just shades of gray. Other images were “hue rotated,” creating bizarre effects such as a red swimming-pool or blue trees. A small patch in the center of the image was left unaltered.

Examples of original and recolored images. (Credit: Cohen & Rubenstein 2020 Cognition)

The researchers quizzed the participants immediately after they viewed the final image. Remarkably, few participants reported seeing anything odd. Both the desaturation and the hue rotation were equally hard to spot.

In the version of the task where the participants had to look for faces in the center of the images, 75 percent of people didn’t spot the distortion. Forty percent failed to spot the trick even during the indoor-vs.-outdoor scene task. The difference was probably due to the fact that the face task demanded more attention to the center of the image (where the color were normal).

The authors conclude that our moment-to-moment perception isn’t as colorful as it seems:

Here, we examined how much color information could be processed “in the blink of an eye” … these results highlight how the immediate percept of a single fixation is shockingly impoverished and lacks a surprising amount of color.

But is this just a laboratory trick? Probably not. Although a 288-millisecond view of an image might seem brief, the authors note that this is roughly the duration of the average gaze fixation when we’re viewing complex scenes.

In other words, a good proportion of our natural visual experience is composed of brief views like the pictures in this study. Yet in day-to-day life, we never suspect that much of our visual input is devoid of useful color information.

How, then, does the illusion of full technicolor vision arise? The authors raise the possibility that our brains essentially extrapolate, based on the limited color information that we do receive:

Under this view, although each independent sampling of the visual world lacks much color in the periphery, those samples are stitched together to create an experience of color across the visual world via color-percept integration.

This suggestion is not entirely new. Indeed, the question of how we experience a rich, stable and seamless visual world, despite our limited and ever-changing vision, is an old one.

Cohen’s and Rubenstein’s hue-distorted images are a new and, well, colorful demonstration of this old problem.