Why do certain gems hold such an emotional significance for so many? Talismanic adornments are in demand, writes Andrea Marechal Watson, and have an intriguing history.

S

Special powers have always been attributed to gems. Early humans believed that the strange bright stones they found in mountains and on river beds, created by mysterious underground forces, were godlike. Countless legends spanning cultures – from Ancient Greek to Aboriginal – share the notion that jewels are of divine or superhuman origin. Amethyst was said to have been created from the tears of the Greek god Dionysus, and onyx from the fingernails of Venus, while for the Aboriginals of southern Australia opals were created when their ancestral God came to Earth in a rainbow.

More like this:

– The ultimate power adornment?

– The story of the ‘queen of flowers’

– A new way of living and dressing

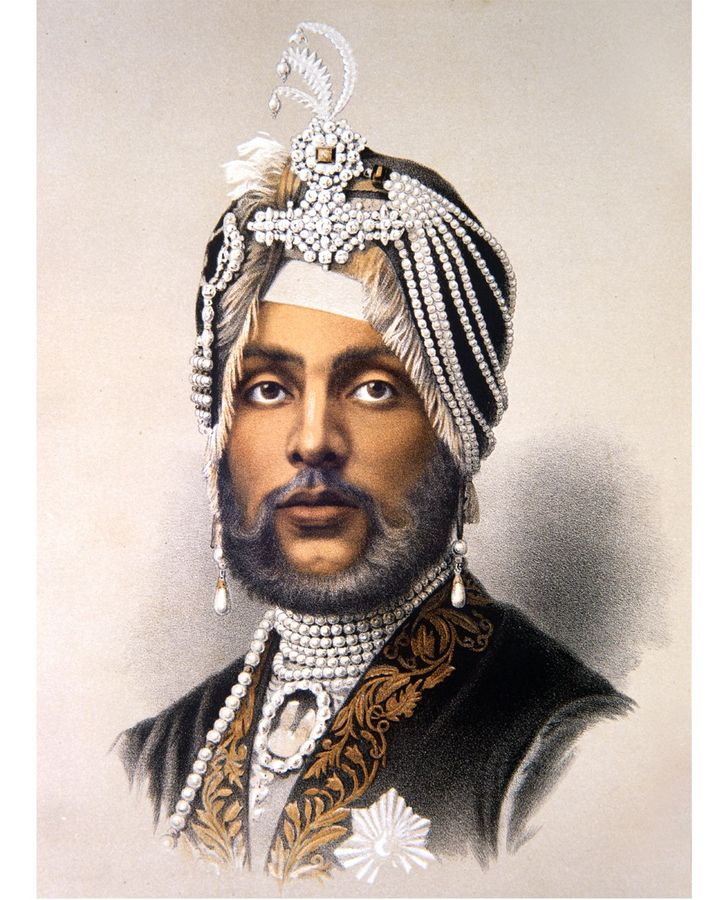

Throughout history, the talismanic quality of gems has been significant. Moonstone was believed to be a way of communicating with the gods; jade was (and still is) used to attract good fortune; rubies were said to help in warfare; emeralds to protect travellers, and diamonds were supposed to have powers over love and health – but could also be used as a poison. Pearls were a symbol of power for kings, queens, Maharajas and Chinese Emperors.

Maharaja Duleep Singh adorned in pearls, which signified status (Credit: Alamy)

The soft power of jewels has been endlessly exploited by diplomats, traders and of course lovers. Roman author and philosopher Pliny the Elder wrote that Cleopatra dissolved a priceless pearl in vinegar to impress Marc Antony. In modern times, De Beers’ famous marketing slogan ‘a diamond is forever’ created the notion that all engagement rings must have a diamond.

The emotional hold that gems have over us is reflected in a current interest in jewellery that is unique and characterful. “In our end of the industry, big sparkly diamonds are not the thing at all,” says Harriet Scott of UK-based jeweller Goldsmiths, whose annual fair takes place this month. “People are looking for something more individual and also affordable.”

A bespoke cocktail ring by Castro Smith features a gemstone re-purposed from another item of jewellery (Credit: Goldsmiths’ Fair)

Stories of unusual commissions abound, among them a ring created by Vicki Ambery-Smith, inspired by real and imagined architecture. “One of my rings celebrates a 10th wedding anniversary based on places of significance: St Ebbe’s Church where my client was married, her home in Oxford and even her car.” Recent Royal College of Art graduate Gearry Suen turns heirloom pieces into modern designs, using 3D modelling combined with ancient techniques like jade carving. Castro Smith specialises in bespoke signet rings – another item that is enjoying a revival.

All that glitters

Although upcycling and recycling of heirloom pieces is also currently experiencing a surge in popularity, it’s not a new phenomenon. “Recycling gemstones has been going on since Roman times, which is partly why so little jewellery survives outside of royal and museum collections,” says Tricia Topping of Goldsmiths.

A personalised gold-and-garnet necklace of Ancient Egyptian King Senwosret ll (1887-1878 BC) (Credit: Alamy)

A wave of repurposing followed the execution of Charles I when Oliver Cromwell had the crown jewels either destroyed or repurposed, and their gold settings turned into coins stamped with ‘Commonwealth of England’. Refashioning jewels was one of the ways that Cartier built its business in the early 20th Century. And perhaps the most famous – and controversial – example of a refashioned jewel is that of the Koh-i-Noor. One of the largest cut diamonds in the world, it was ceded to Queen Victoria after the British annexation of the Punjab in 1849, and exhibited at the 1851 Great Exhibition. At Prince Albert’s insistence, the stone was recut to make it sparkle more, reducing its size dramatically but answering the tastes of the day.

Often settings are old fashioned and pieces therefore often go unworn. The stones they contain are far more desirable, however. “I want a cocktail ring that can be worn with jeans,” one client told jeweller Maya Selway, who liberated an emerald from an outdated setting.

And the story behind Shimell and Madden’s Lifeline brooch, created for Annette Austin, again demonstrates the emotional power of stones.

The Lifeline brooch by Shimell and Madden was created by re-setting gemstones from the client’s existing jewellery collection (Credit: Goldsmiths’ Fair)

“I have been trying to simplify my life – selling, giving away or throwing out, and this included going through my jewellery box,” Austin tells BBC Culture. “Having given away all the unwanted pieces, I was left with a number of gemstones in old-fashioned settings, each of which told a tale of my life and travels. Shimell and Madden reset the stones in a single brooch which I now wear regularly. They include a garnet – my birthstone – from a ring given to me on my 16th birthday and an amethyst found by a great uncle when fossicking [gem hunting] in the Outback, and presented to me when I was 21.”

Ellis Mhairi Cameron reworked two wedding rings for a couple, both widowed, who decided to carry their previous partners’ memories with them by having the stones reset in the original gold. “I took the heirloom diamonds from both rings and reset them, adding a few more diamonds to fit with the design the lady liked.”

Wedding rings by Ellis Mhairi Cameron feature re-fashioned heirloom diamonds already owned by the couple (Credit: Goldsmiths’ Fair)

London jeweller Esther Eyre, whose clients include Gwyneth Paltrow and Tilda Swinton, says attitudes to re-modelling have changed. “When I was first asked to re-mount some jewellery… I was horrified. I had a deeply-held English attitude that jewels should be kept as they were. Not so in the eyes of Middle Eastern ladies – they had a lot of jewellery, and would regularly have their pieces reworked into something more fashionable. Much of my work since then has been helping clients to re-imagine their jewels into pieces they really want to wear.”

Recycling gemstones also helps address growing concerns over the ethics of the jewellery trade. “Ethical and Fairtrade jewellery is a growing area and there’s much more education out there, but it is not foolproof. A lot of green-washing is also going on,” says Scott.

Jewellery that is upcycled and sustainable, such as this Fairtrade gold brooch by Ute Decker, is increasingly in demand (Credit: Goldsmiths’ Fair)

Diamonds in particular have a mixed reputation, in part due to the 2006 Leonardo DiCaprio blockbuster Blood Diamond, with its biting commentary on the dark side of the trade. The same year as filming took place (2005), the Responsible Jewellery Council was founded to advance ethical, human rights and environmental practices in the supply chain. “The film did a great job,” says Scott.

When the Victoria & Albert Museum’s jewellery gallery was re-opened in spring of 2019, the museum took the opportunity to acquire its first Fairtrade piece, a gold brooch called The Curling Crest of a Wave by Ute Decker, a maker who is also at the forefront of a drive to sustainability. Fairtrade gold ensures a fair price as well as setting standards on working conditions, health and safety, child labour and the environment.

A temple painting in Bihar, India, depicts a woman adorned in symbolic gold (Credit: Alamy)

“In a world where sustainability is now the buzzword, jewellery is the ultimate in recycling,” says Eyre. “It’s an interesting conjecture that particles of the gold in modern pieces may have been worn by the Ancient Egyptians.”

Goldsmiths’ Fair is on until 6 October. A programme of free talks will be running.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.