In the first of BBC Culture’s series The American Century, Cameron Laux looks at how The Age of Innocence – published 100 years ago – marked a pivotal moment in US history.

A

A funny story. Edith Wharton was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for her novel The Age of Innocence in 1921 (it was published in 1920), but the jury had originally chosen to award it to Sinclair Lewis’s Main Street. The trustees, the actual powers-that-be within the organisation, to whom it falls to make the final decision based on the advice of the jury, balked at the choice because they thought Main Street was unwholesome. Back then, the prize was to be awarded to a novel “which shall best present the wholesome atmosphere of American life”, and Main Street, a trenchant satire on narrow-mindedness in a small midwestern town, ruffled some self-important feathers. In the book, a married man perhaps has an affair with a neighbour, while his wife contemplates an affair with a younger man, but does nothing about it – these are the only morally racy bits I can come up with. No, the problem was actually political: then, as now, the rural Midwest was considered to be the sacred beating heart of America (Mom and apple pie and all that), and it wouldn’t do to question that myth.

More like this:

– Why women write under men’s names

– The remarkable cult of Elena Ferrante

– Surprising secrets of writers’ first drafts

Some of this belief that literature should mind its manners survives to this day. For example, Thomas Pynchon and Don DeLillo, universally acclaimed as masters of the 20th-Century US novel, and both of whom mercilessly target the American dream, have been passed over for Pulitzers. When the 1974 jury unanimously recommended Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow (probably among the most important novels ever written), the trustees chose to give no award rather than to give it to him.

But back to Lewis. Another of his books was then awarded the Pulitzer in 1926; supremely annoyed by his first go-around with them, he gave the award back. Then in 1930 he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature – surely, one might think, establishing him as a global force in writing. Yet how many people today have even heard of Sinclair Lewis, let alone read one of his books? He has, for the most part, been swallowed by time (as have many of the Pulitzer laureates from that era: Ernest Poole, Margaret Wilson, Edna Ferber, Louis Bromfield, Julia Peterkin…), while Wharton flourishes. She has left him in her dust. In recent decades, two cinematic auteurs have even adapted her books into films stuffed with bankable stars: Martin Scorsese with The Age of Innocence (1993) and Terence Davies with The House of Mirth (2000). If Scorsese takes an interest in something, it must have become part of America’s DNA.

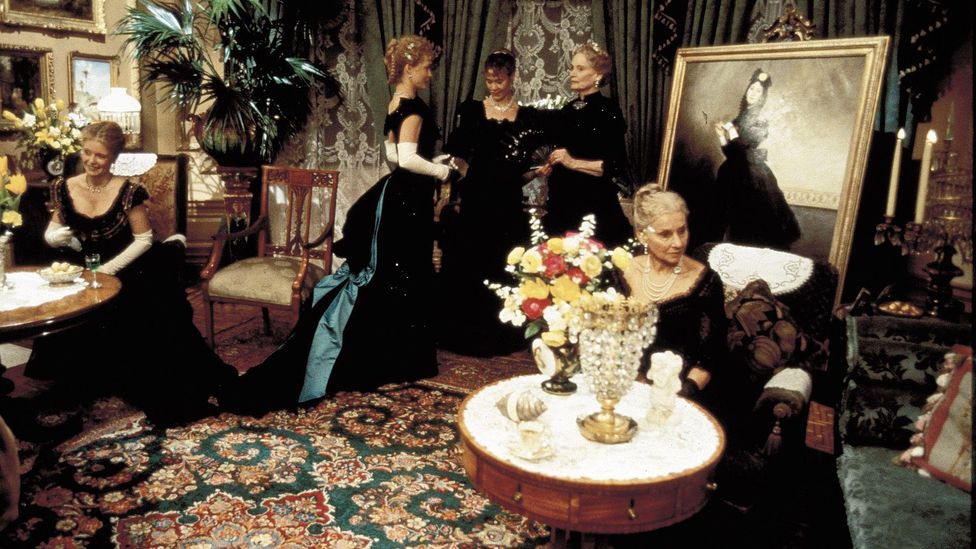

According to The Washington Post, Scorsese “is as deft at exploring the nuances of Edwardian manners as he is the laws of modern-day machismo” (Credit: Alamy)

Why has The Age of Innocence endured? It and Main Street are alike in being almost anthropological explorations of tribal cultures: the former of upper-crust New York society in the 1870s, the latter of small-town Minnesota in the 1910s. Both are “hieroglyphic worlds” (Wharton’s phrase from The Age of Innocence) of brittle convention under which the human spirit roils. The protagonists of both rebel against society, but ultimately give up. Yet, while Main Street is supposed to be a naturalistic masterpiece (to the point, I would argue, of tedium), The Age of Innocence offers more: there is something elegant and complicated going on with its poetics (Wharton is a strikingly sophisticated writer without ever being showy), and the final chapter of the book leaps forward in time in such a way that the novel devastatingly captures the passage of an era. The author Colm Toibin tells BBC Culture that he thinks of it as a “stylish book about disappointment, written… by someone who knew that world but is clear-eyed rather than nostalgic about its demise”.

The shift to modernity

Wharton was living in Paris during the Great War and threw herself into the war effort, “working on behalf of the hundreds of thousands of refugees who flooded across the French border”, as the writer Elif Batuman (herself shortlisted for a Pulitzer this year) notes in her foreword to the new Penguin edition of Age of Innocence. After the war, a changed person, Wharton sat down to write about how the Gilded Age of her girlhood had yielded inexorably to modernity. Janet Beer, professor of literature at Liverpool University and a Wharton expert, tells me that she regards The Age of Innocence as “an almost perfect example of the genre of historical novel”: it “has her at the height of her powers and totally in control of the subject, the genre, and the conviction that this was the only way to commemorate a society now dead”.

Wharton’s novel is set at the cusp of a new age, moving on from outdated modes of behaviour – and ways of living (Credit: Getty Images)

To get a sense of what a gilded cage the Gilded Age was, watch Scorsese’s film and marvel at the canyons of mahogany and reefs of crystal these people swam through – the hushed, heavily encrusted formality of an upmarket funeral home. Toibin, in his introduction to the Scribner edition (2020), calls this the “twilight time” of the old New York aristocracy. Twilight indeed. The novel signals that the “elaborate futility” of an elite way of life, in which work features as a hobby, was about to be overcome by what Beer calls “the unstoppable power of new money, financial profiteering, rising materialism, and family breakdown”. It is an unsentimental modernist critique of a genteel stratum of society for whom the 20th Century figures as a storm on the horizon.

With an implacable eye, Wharton observes what Toibin calls Old New York’s “stylised social rigidities”. As I read the novel, I am struck by how impossible people find it to put emotion into words: they are forever “blushing”, “reddening”, “flushing”, or otherwise indicating embarrassment at the unspoken. “The persons of their world lived in an atmosphere of faint implications and pale delicacies,” writes Wharton.

According to Toibin, Wharton captured Old New York’s “stylised social rigidities” – in which emotions were rarely expressed (Credit: Getty Images)

The book opens with its major characters attending an opera, but the real drama, the real motions being gone through here, are happening among the audience members, who are performing for each other. Batuman, who in 2018 actually ended up a writing fellow at the Mount, Wharton’s former home in Massachusetts, tells BBC Culture that while she was re-reading The Age of Innocence at the time, “I was deeply struck by… Wharton’s view of the transactional nature of family and the role-playing it requires”. The structural dishonesty of Old New York shows many signs of being under great strain. When Newland Archer, Wharton’s lead character, is pulled between the formal demands of being a member of a prestigious New York family, and the personal longing to lead an unconstrained, honest, and passionate life, his mind almost breaks.

As The Age of Innocence opens, Archer is on course to marry May Welland, a society ingenue (all well-bred girls are trained in “factitious purity”). It is an appropriate match – essentially an arranged marriage. But when the cosmopolitan and free-spirited Countess Olenska appears in their social circle, Archer is strongly drawn to her, and the scene is set for a psychological struggle between duty and desire, the slumber of convention and feverish personal awakening. So far, so period novel. Wharton’s brilliant move is to suddenly and brutally frame the period in a final chapter, a coda, that leaps into the future 26 years.

Archer, now 57, contemplates how he ended up sinking back into a marriage with May and having three children. He reviews “the packed regrets and stifled memories of an inarticulate lifetime” and accepts them. His cultural obsolescence weighs heavily on him. But he has also fought his way to a certain maturity; his acknowledgement of all his regrets somehow rounds him out as a sympathetic and admirable person. Batuman says that The Age of Innocence is a “touchstone” for her because it “plays with… the relationship between youth and middle age”. The final chapter of the book lifts it into the big league.

Although Wharton was the first woman to win the Pulitzer, in her youth she was discouraged from writing (Credit: Alamy)

Her Pulitzer may have been a second choice, but Wharton was the first woman to receive one – and she has done it justice. When she was young, her mother was disgusted by her writing, and forbade her to read novels. After she freed herself of her own dud society marriage, in her 40s, she revelled in her liberty, and threw herself into her fiction. A century later, writers such as Lionel Shriver hail her as a hero. Shriver has argued that “100 years ago, Edith Wharton’s drive, independence, wilfulness and autodidactic mastery of the English language were extraordinary, and I bashfully claim her as a kindred spirit”. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie said in 2019 that she was “reading all of Edith Wharton” because she understood “the texture of character and she gets human beings”. Jonathan Franzen is a great admirer: “She was a doer, an explorer, a bestower, a thinker.” Ta-Nehisi Coates has confessed to being blown away; “what I love about Wharton… is her empathy and ambivalence”.

Wharton was no friend of change. She didn’t like feminism, and she saw the worship of status in Old New York being swept away and replaced by the worship of money – hardly a forward step. But the story of Newland Archer and his tribe (also her own tribe, let’s not forget) is expressed with an elegant and complex ambivalence. I was in my early 20s when I first read the book, and then I saw it as a parable of cold-blooded repression and wasted youth. Now I am almost 57 myself, and I see it as a shrewd meditation on desire and regret. I bow to The Age of Innocence, 100 years old but ageless.

Love books? Join BBC Culture Book Club on Facebook, a community for literature fanatics all over the world.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.