On 6 and 9 August, it will be 75 years since the US dropped atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki towards the end of World War Two.

Image copyright

Getty Images

The recorded death tolls are estimates, but it is thought that about 140,000 of Hiroshima’s 350,000 population were killed in the blast, and that at least 74,000 people died in Nagasaki.

The bombings brought about an abrupt end to the war in Asia, with Japan surrendering to the Allies on 14 August 1945.

But critics have said that Japan had already been on the brink of surrender.

Those who survived the bombings are known as hibakusha. Survivors faced a horrifying aftermath in the cities, including radiation poisoning and psychological trauma.

British photo-journalist Lee Karen Stow specialises in telling the stories of women who have witnessed remarkable events in history.

Stow photographed and interviewed three women who have vivid memories of the bombings 75 years ago.

This article contains details some people may find upsetting.

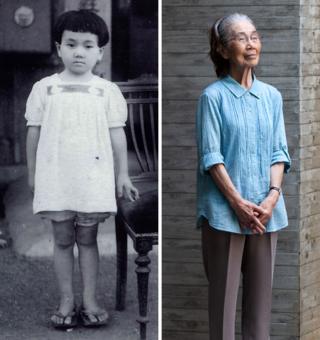

Teruko Ueno

Teruko was 15 years old when she survived the atomic bomb in Hiroshima on 6 August 1945.

Image copyright

Lee Karen Stow

At the time of the bombing, Teruko was in her second year of nursing school at the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital.

After the bomb hit, the students’ dormitory of the hospital caught fire. Teruko helped to fight the flames, but many of her fellow students died in the blaze.

Her only memories of the week after the bomb are of working day and night to treat victims with horrific injuries, while she and others had no food and little water.

After graduating, Teruko continued to work at the hospital, where she assisted with operations involving skin grafts.

Skin was taken from a patient’s thigh and grafted on to an area that had developed a keloid scar as a result of burns.

She later married Tatsuyuki, another survivor of the atomic bomb.

When Teruko became pregnant with their first child, she was worried about whether the baby would be born healthy and if it would survive.

Image copyright

Lee Karen Stow

Her daughter Tomoko was born and thrived, giving Teruko courage in raising her family.

Image copyright

Lee Karen Stow

“I haven’t been to Hell, so I don’t know what it’s like, but Hell is probably like what we went through. It must never be allowed to happen again,” says Teruko.

“There are people making strong efforts to abolish nuclear weapons. I think the first step is to make the local government leaders take action.

“And then we must reach out to the leaders of the national government, and to the whole world.”

Image copyright

Lee Karen Stow

“People said no grass or trees would grow here for 75 years, but Hiroshima revived as a city with beautiful greenery and rivers,” says Teruko’s daughter Tomoko.

“[However] the hibakusha have continued to suffer from the after-effects of radiation.

“While the memories of Hiroshima and Nagasaki are fading from the minds of people … We are standing at a crossroads.

“The future is in our hands. Peace is possible only if we have imagination, think about other people, find what we can do, take action, and continue tireless efforts each day to build peace.”

Kuniko, Teruko’s granddaughter, adds: “I didn’t experience the war or the atomic bombing, I only know Hiroshima after it was rebuilt. I can only imagine.

“So I listen to what each hibakusha says. I study the facts of the atomic bombing based on evidence.

“On that day, everything was burned in the city. People, birds, dragonflies, grass, trees — everything.

Image copyright

Getty Images

“Of the people who entered the city after the bomb for rescue activities – and those who came to find their families and friends – many died. Those who have survived are suffering from illnesses.

“I have tried to have closer ties not only with hibakusha in Hiroshima and Nagasaki but also with uranium mine workers, people who live near those mines, people involved in developing and testing nuclear weapons, and downwinders [those who suffered sickness as a result of nuclear weapon testing].”

Emiko Okada

Image copyright

Yuki Tominaga

Emiko was eight years old when the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima.

Her elder sister, Mieko, and four other relatives were killed.

Many photographs of Emiko and her family were lost, but those kept at the homes of her relatives survived, including those of her sister.

Image copyright

Courtesy of Emiko Okada

“My sister left home that morning, saying, ‘I’ll see you later!’ She was just twelve years old and so full of life,” says Emiko.

“But she never returned. No one knows what became of her.

“My parents searched for her desperately. They never found her body, though, so they continued to say that she must still be alive somewhere.

“My mum was pregnant at the time, but she miscarried.

“We had nothing to eat. We didn’t know about radiation, so we picked up anything we could find without thinking about whether it was contaminated or not.

“Because there was nothing to eat, people would steal. Food was the biggest problem. Water was delicious! This was how people had to live at first, but it’s been forgotten.

Image copyright

Courtesy of Emiko Okada

“Then my hair started falling out, and my gums started bleeding. I was constantly exhausted, always having to lie down.

“No one at the time had any idea what radiation was. Twelve years later, I was diagnosed with aplastic anaemia.

“Every year there are a few times when the sky at sunset is deep red. It’s so red that people’s faces turn red.

“At those times I can’t help but think of the sunset on the day of the atomic bombing. For three days and three nights, the city was burning.

“I hate sunsets. Even now, sunsets still remind me of the burning city.

Image copyright

Getty Images

“Many hibakusha died without being able to talk about these things, or their bitterness over the bombing. They couldn’t speak, so I speak.

“Many people talk about world peace, but I want people to act. I want each person to start doing what they can.

“I myself would like to do something so that our children and grandchildren, who are our future, can live in a world where they can smile every day.”

Reiko Hada

Reiko Hada was nine years old when the atomic bomb was dropped on her home town of Nagasaki at 11.02 on 9 August, 1945.

Image copyright

Lee Karen Stow

Earlier that morning, there was an air-raid warning, so Reiko stayed home.

After the all-clear was sounded, she went to the nearby temple, where children in her neighbourhood would study instead of going to school, because of frequent air-raid warnings.

After about 40 minutes of study at the temple, the teachers dismissed the class, so Reiko went home.

“I made it to the entrance of my house, and I think I even took a step inside,” Reiko explains.

“Then it happened all of a sudden. A blazing light shot across my eyes. The colours were yellow, khaki and orange, all mixed together.

“I didn’t even have time to wonder what it was… In no time, everything went completely white.

“It felt as if I had been left all alone. The next moment there was a loud roar. Then I blacked out.

Image copyright

Getty Images

“After a while, I came to. Our teacher had taught us to go to an air-raid shelter in case of emergency, so I looked for my mother inside the house, and we went to the air-raid shelter in our neighbourhood.

“I didn’t have a single scratch. I had been saved by Mount Konpira. But it was different for the people on the other side of the mountain; they suffered atrocious conditions.

“Many fled over Mount Konpira to our community. People with their eyes popped out, their hair dishevelled, almost all naked, badly burned with their skin hanging down.

“My mother grabbed towels and sheets at home and, with other women in the community, led the fleeing people to the auditorium of a nearby commercial college where they could lie down.

“They asked for water. I was asked to give them water, so I found a chipped bowl and went to the nearby river and scooped water to let them drink.

“After drinking a sip of water, they died. People died one after another.

“It was summer. Because of the maggots and the terrible smell, the bodies had to be cremated immediately. They were piled up in the swimming pool at the college and cremated with scrap wood.

“It was impossible to know who those people were. They didn’t die like human beings.

Image copyright

Courtesy of Reiko Hada

“I hope future generations will never have to go through a similar experience. We must never allow these [nuclear weapons] to be used.

“It is people who create peace. Even if we live in different countries and speak different languages, our wish for peace is the same.”

Image copyright

Lee Karen Stow

All photographs subject to copyright.

Read MoreFeedzy