Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s plan to tackle climate change is the latest in a long list of government pledges and targets on the environment.

Successive prime ministers – both Labour and Conservative – have set targets on everything from carbon emissions to tree planting.

“UK government’s record on environmental targets is a bit hit and miss – but mostly miss,” says Doug Parr, policy director at Greenpeace UK.

“Targets are a great way of expressing government vision and ambition, but they become meaningless without the policies, funding, regulation and enforcement necessary to see them delivered.”

So how successful have British governments been in meeting their green targets?

During its first year in office, the Labour government under Tony Blair committed to cutting UK carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions by 2010 to 20% below 1990 levels.

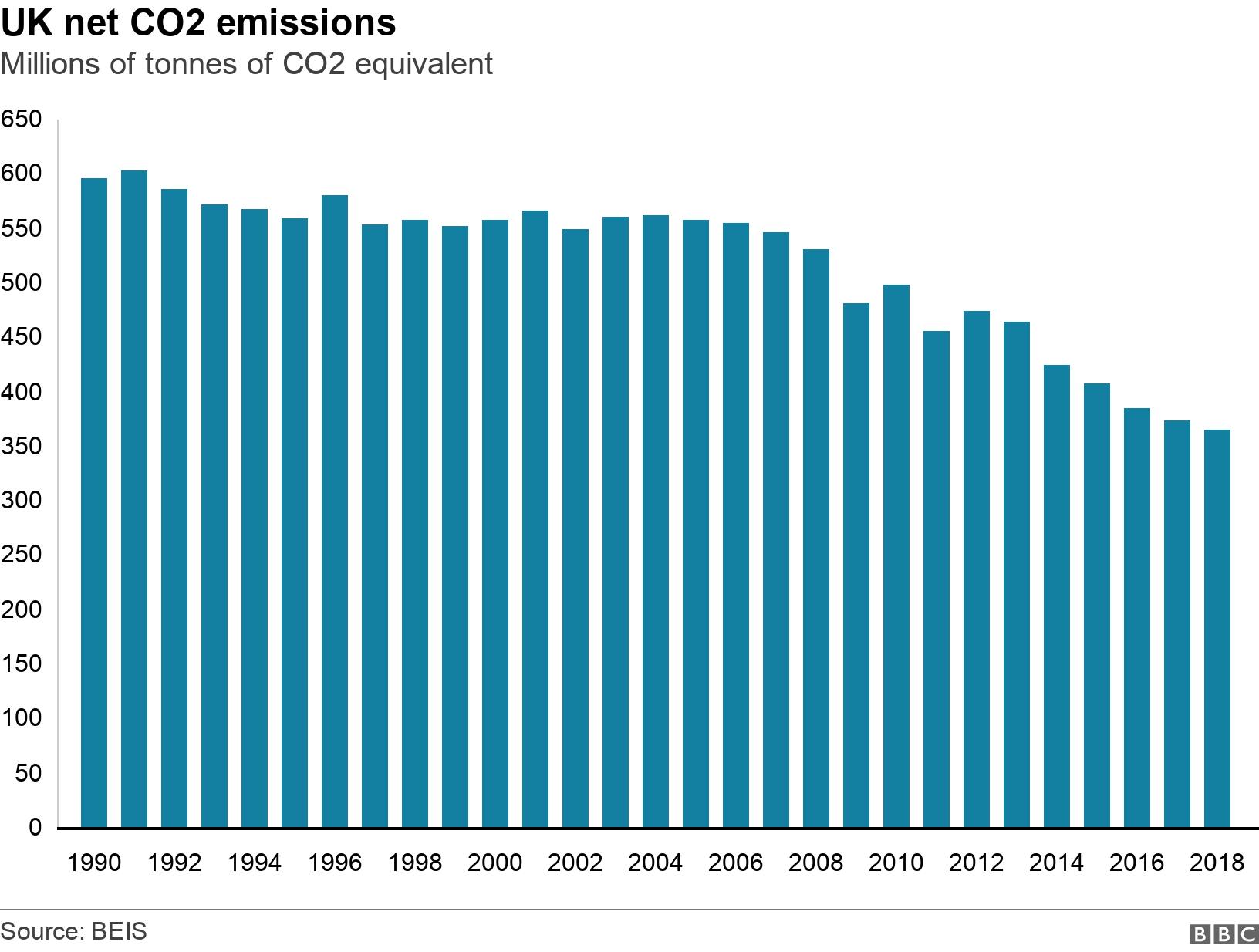

In 1990, total CO2 emissions stood at 595.7 million tonnes of CO2 equivalent (MtCO2e), according to official data. By 2010, this figure had decreased to 498.5 MtCO2e.

That’s a reduction of 16.3%, which means Labour fell short of its target.

The Labour government did, however, succeed in meeting a less ambitious target of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 12.5% by 2010 as part of an international agreement known as the Kyoto Protocol.

Greenhouse gases include not just carbon dioxide but other polluting gases such as methane and nitrous oxide.

Between 1990 and 2010, total greenhouse gas emissions fell by 24.3%.

In 2019, the UK became the first country to pass a law requiring the government to reach net-zero emissions by 2050.

Net zero would mean the country would be removing as much carbon from the atmosphere as it was emitting.

Having targets that far in the future creates problems.

“Nobody can speak for future governments, so unless targets can be future-proofed they are unlikely to be effective,” said Ruth Chambers from Greener UK, a coalition of environmental organisations.

But the Climate Change Committee, an independent public advisory body, is monitoring whether the UK is on track to meet this one.

Its recent report concluded that the UK power sector was adapting to meet the net-zero target thanks to contracts to construct large-scale wind and solar energy projects.

However, the report also warned the government that it would have to move faster to decarbonise industry, transport and construction if it was going to stay on track for its target.

In 2000, the Labour government outlined plans to increase the use of renewable energy to power the UK’s electricity grid, pledging to generate 10% of electricity from renewables by 2010.

Renewable energy refers to energy sources such as wind and solar, which are not depleted when used and tend to generate power without causing pollution or emissions.

When Labour left government in 2010, however, renewable energy sources generated enough power to fuel just 6.9% of the electricity grid. According to government data, renewables – mainly wind, solar and biomass – contributed 26.2 terawatt-hours (TWh) out of a total of 382.1 TWh.

However, the use of renewables did more than double over this period – it had only been 2.8% in 2000.

image copyrightGetty Images

In 2006, then-Chancellor Gordon Brown pledged to make the UK one of the first countries to adopt a low-carbon housebuilding policy by introducing the Code for Sustainable Homes.

His government then announced that from 2016 all new homes would be zero carbon thanks to changes to the planning system and a gradual tightening of building regulations.

This would involve new homes generating power using solar panels and wind turbines to offset their emissions of greenhouse gases.

In 2011, the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition government under David Cameron carried over this pledge to that year’s Budget, but added that carbon emissions could be offset by the use of devices both on-site and off-site.

But in 2015 the Conservative government scrapped the new regulations, meaning there would no longer be an obligation on housebuilders from 2016 onwards to achieve zero-carbon.

Of the more than 210,000 houses built in 2016 only 18,922 (or 9.0%) achieved the highest environmental impact rating, meaning the vast majority were not zero-carbon.

In 2018, Theresa May’s government announced a commitment to reach 12% forest cover in England by 2060, which would involve planting 5000 hectares a year. A hectare can contain between 1,000 and 2,500 trees, so at a midpoint, 5,000 hectares would be just under nine million trees.

In the first year after the announcement, 1,420 hectares were planted.

Trees currently cover about 10% of English land, far behind the EU average of 38%.

The government says it wants to work with landowners to grow woodland cover, and highlights schemes like a £19m fund to encourage large-scale planting and grants of up to £6,800 per hectare to plant and protect trees.

image copyrightReuters

The UK’s targets on air quality come from the EU’s Air Quality Directive of 2008, which sets limits for the amount of certain pollutants that may be found in the air.

It became part of UK law in 2010, with separate legislation in each of the four nations. The government has been clear that it does not plan to change these targets after Brexit, although clearly they will no longer be enforced by EU institutions.

In 2014, the EU Commission began proceedings against the UK for failing to meet nitrogen dioxide (NO2) targets, which was followed by a final warning in 2017 for repeated breaches. There was then action in the European Court of Justice against the UK in 2018.

The EU directives also allow private groups to take legal action in the UK courts against the government for failing to meet air quality targets.

A group called ClientEarth did just this, which led to the Supreme Court repeatedly ordering the government to come up with new air quality plans because existing ones were not good enough.

The UK adopted the EU’s 2000 Water Framework Directive, which required all member states to achieve at least “good” status for all bodies of water by 2015.

Water quality is a devolved matter, but the combined statistics show that in 2015, 30% of bodies of surface water were “good” and 5% were “high”, with the proportion being good or better having barely changed since 2008.

The directive allowed for the target to be extended to 2027 at the latest and for lower targets to be set under certain circumstances.

A Defra official said in 2012 that the UK would not meet the 100% “good” target by 2027 and was instead hoping to achieve 75% “good” by that time.

An Environment Agency report earlier this year said all of the rivers, lakes and streams in England are polluted and there had been no progress towards the target of 100% healthy waters by 2027.

Reporting by Oliver Barnes, Nicholas Barrett & Anthony Reuben

Read MoreFeedzy