Two little Arctic ice caps that Mark Serreze studied as a graduate student in the early 1980s might not have been as grand and dramatic as other features of our planet’s cryosphere, but to him they nonetheless were quite special.

Were quite special — past tense — because Serreze, who now directs the National Snow and Ice Data Center, has confirmed that the two ice caps on the Hazen Plateau of Canada’s Ellsmere Island have disappeared. They’re the victims of human-caused warming that has occurred three times more rapidly in the Arctic than anywhere else.

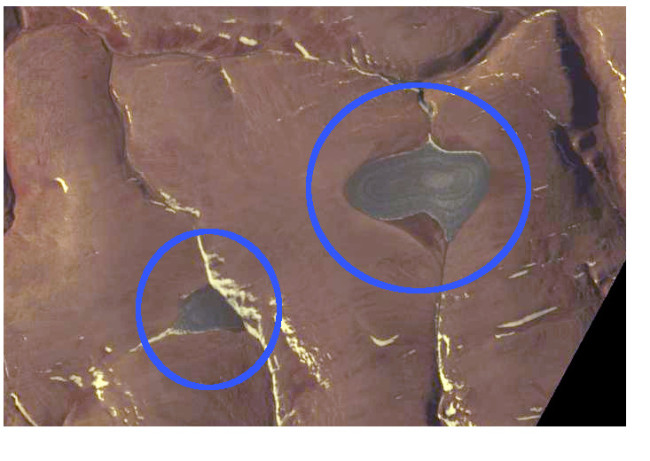

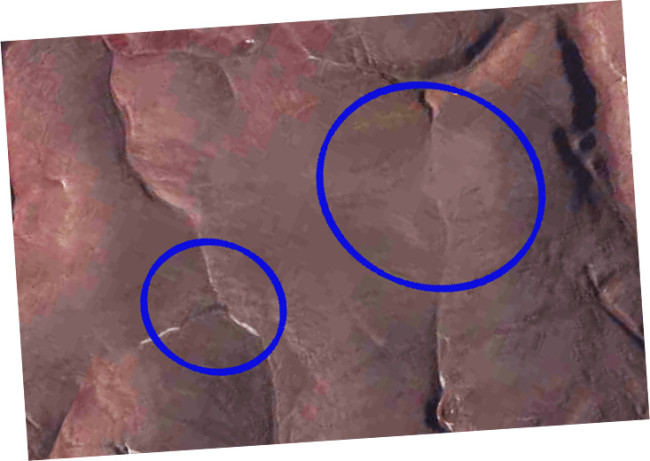

The disappearance was confirmed using recent images from the ASTER instrument aboard NASA’s Terra satellite.

The top image, acquired by the ASTER instrument aboard the Terra satellite, shows the St. Patrick Bay ice caps in 2015. The bottom image, acquired by the same instrument in 2020, shows that they’re gone. (Credit: NSIDC)

“When I first visited those ice caps, they seemed like such a permanent fixture of the landscape,” Serreze says. “To watch them die in less than 40 years just blows me away.”

Serreze first visited the ice caps in 1982. The region is a polar desert — a very dry, very cold place. He was drawn to do the work in this inhospitable environment because “I grew up in Maine where we had real winters and I loved snow and ice.” (He also reports that he got very good at “riding ice floes down the Kennebunk River.”)

As with many people who visit the Arctic, he was smitten by the landscape. “A ski-equipped Twin Otter dropped us off at the top of the bigger ice cap,” he says. “It was a rare, clear windless morning. I was awed by the pristine whiteness of the snow, the absolute silence, that I could see 50 miles in every direction, and that I may well have been standing on ground that nobody had ever stood on before.”

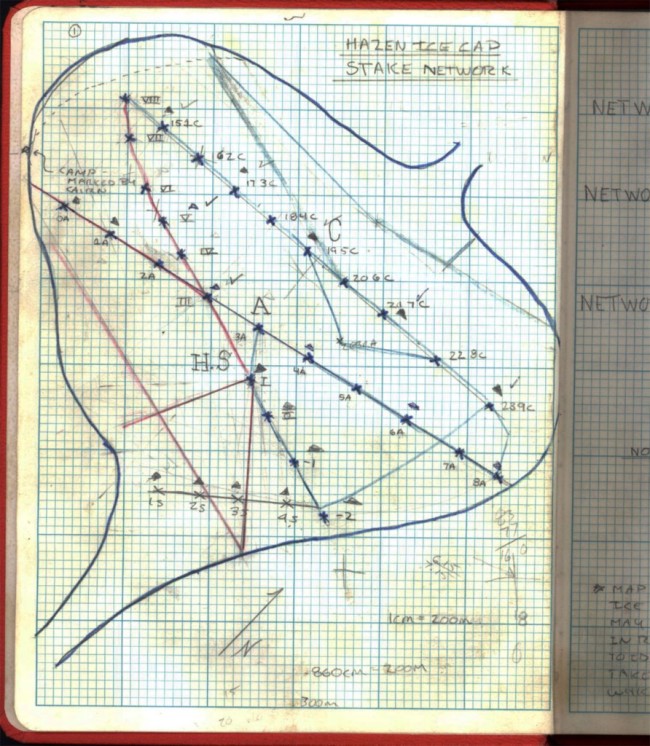

A page from Mark Serreze’s field book shows a network of stakes he and fellow researchers laid out on the larger of the two St. Patrick Bay ice caps in 1983. (Credit: Mark Serreze via NSIDC)

Decades later, he knew that warming temperatures were bringing about the demise of these features, known as the St. Patrick Bay ice caps. Gathering all the evidence, he and colleagues published a paper in 2017 predicting they would disappear within five years. Now we know they were right.

As a story posted today on the NSIDC website explains:

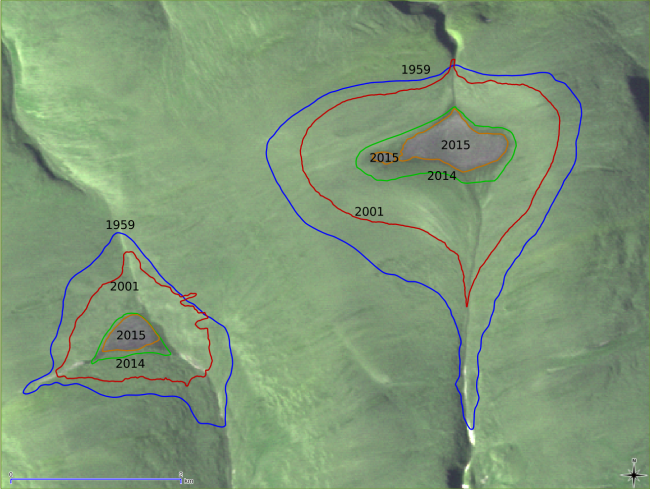

“In 2017, scientists compared ASTER satellite data from July 2015 to vertical aerial photographs taken in August of 1959. They found that between 1959 and 2015, the ice caps had been reduced to only five percent of their former area, and shrank noticeably between 2014 and 2015 in response to the especially warm summer in 2015. The ice caps are absent from ASTER images taken on July 14, 2020.”

The shrinkage of the St. Patrick Bay ice caps between 1959 and 2015 is documented in this graphic from the 2017 paper by Serreze and his colleagues. The 1959 outlines are based on aerial photography. Those for 2001 come from GPS surveys. And the 2014 and 2015 outlines come from ASTER imagery. (Source: NSIDC)

Even though the disappearance was no surprise, it hit Serreze hard. “It was like watching a sick friend slowly waste away from some awful disease,” he says. “I knew the end was coming, but still couldn’t be completely prepared for it.”

The St. Patrick Bay ice caps comprised half of a group on the Hazen Plateau, all believed to be relics of the Little Ice Age, a period of cooling temperatures which began around the start of the fourteenth century and lasted until the 1800s. The two others, the Murray and Simmons ice caps, are at a higher and thus colder elevation. They have not been shrinking as quickly, but they are likely doomed to follow in the footsteps of their siblings.

I asked Serreze what people should take away from what’s happening. Here was his answer:

“Climate change is very, very real, and as long predicted, the Arctic is leading the way. We are geoengineering our planet, and we don’t seem to want to accept that we’re headed for a very different world.”