image copyrightGetty Images

Europe’s fur industry is back in the spotlight after Denmark’s mass culling of millions of mink following an outbreak of coronavirus at farms in the country.

Earlier this month, Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen announced that all mink would be slaughtered. Denmark is the world’s biggest mink producer, farming up to 17 million of the animals, and Covid has swept through a quarter of its 1,000 mink farms.

Officials say this “reservoir” of disease poses a significant health risk for humans, and worry that mutations detected in mink-related strains of the virus might compromise a future vaccine.

But images of mink mass graves and farmers in tears were followed by outcry after the government admitted its order had no legal basis. The agriculture minister has since resigned. On Saturday hundreds of tractors drove into central Copenhagen to protest about the handling of the crisis. There have also been protests in the cities of Aalborg and Aarhus.

image copyrightGetty Images

The proposed ban on mink farming until 2022 now has parliamentary backing but negotiations over compensation are dragging out.

Authorities say all 288 infected herds have been killed and they have put down approximately 10 million animals. It is believed the majority of remaining mink on farms where no infection was detected have also been killed. In a short while, Denmark’s fur industry has almost been wiped out. Around 6,000 jobs are at risk.

“It is a de facto permanent closure and liquidation of the fur industry,” said Danish Mink Breeders Association chairman Tage Pedersen in a statement. “This affects not only the mink breeders, but entire communities.”

Mink farmer Per Thyrrestrup doubts business will ever come back: “To have the same quality of the skins, to have the same colour – it’s going to be 15 to 20 years before that’s possible.”

The world’s largest fur auction house, Kopenhagen Fur, has also announced a “controlled shutdown” over two to three years until this season’s pelts and older stockpiles are sold.

Thousands of buyers, mostly from China, once flocked to auctions held in the Danish capital. It has been a giant in the business, trading 25 million Danish and foreign furs last year.

But even before the pandemic struck, there were signs it was struggling.

A decade ago trade boomed, fuelled by an appetite for luxury goods as Chinese incomes grew. In 2013, Kopenhagen Fur sold about $2bn (£1.5bn) of furs, with global mink production worth $4.3bn.

Mink pelts then cost over $90 (£69) each, but the bubble burst and last year skins fetched only a third of that. Local farmers have struggled to make money – and it is a pattern seen elsewhere. China is by far the biggest fur importer, but it is a major producer too.

Else Skjold, head of fashion at the Royal Danish Academy, says this competition has driven prices down: “A lot of new farmers went into the market and so there was simply an overflow of fur.”

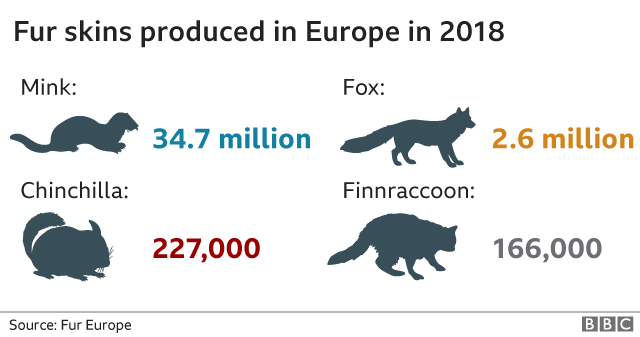

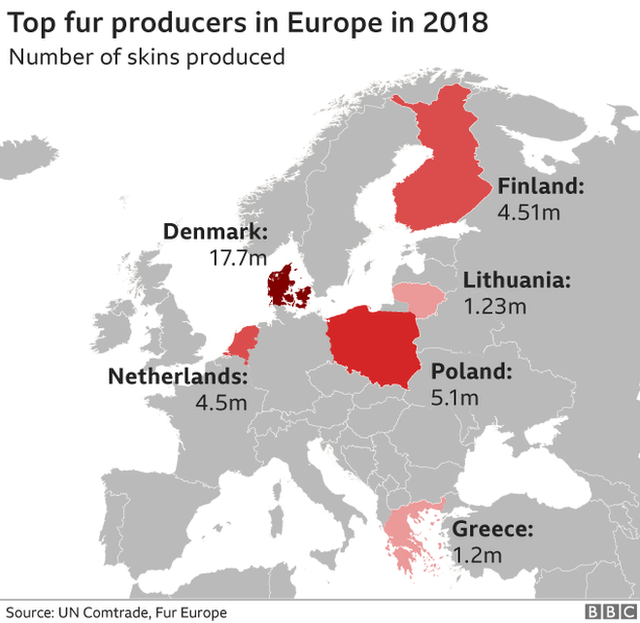

There’s also significant fur farming across Europe. In 2018 there were 4,350 fur farms in 24 European countries, says industry group Fur Europe. Poland, the Netherlands, Finland, Lithuania and Greece are the biggest producers after Denmark – though the US, Canada and Russia also operate farms.

Since the cull began prices have shot up. “People were concerned that there might be a shortage,” says Mark Oaten, chief executive of the International Fur Federation (IFF). Denmark accounts for at least a quarter of the global mink trade.

Ms Skjold thinks foreign competitors will fill the gap: “They will invest hugely in expanding mink farming in China, I suspect.”

Although fur farming is controversial, she believes standards on Danish farms are high and one consequence of Denmark’s exit is a risk that animal welfare could get worse. “We will see farming in less regulated and less controlled countries,” she says.

image copyrightGetty Images

Mink appear particularly susceptible to Covid and it can spread quickly in the farms. Infections have been detected in France, Spain, Sweden, Italy, the US, Greece and the Netherlands, which will now ban fur farming by March 2021.

Animal welfare groups say this is further reason to outlaw the practice, in addition to ethical grounds.

“Fur farms are not only the cause of immense and unnecessary animal suffering, they are also ticking time bombs for deadly diseases,” says Dr Joanna Swabe from the Humane Society International.

Over the years, animal welfare campaigns have shifted public opinion. Numerous fashion brands have stopped using fur and switched to synthetic alternatives.

The UK banned fur farming in 2003. Austria, Germany and Japan have also stopped production and other countries are phasing it out.

image copyrightGetty Images

Yet as European consumers turned away, Chinese customers took their place. “Towards the 2000s you could see the Chinese market grow. Fur represents that you’ve entered the middle class,” says Else Skjold.

The IFF’s Mark Oaten says Asia now accounts for 35-40% of fur sales, with South Korea another key market. Trends have also shifted away from the high-cost “grandma’s fur coat” to affordable, everyday garments with small amounts of fur trim.

But the Chinese market has also faltered. Economic slowdown had dampened consumer spending even before Covid struck. Luxury goods spending “has really taken a dip in the last three years,” says Mr Oaten.

“The whole industry has been struggling,” says Veronica Wang of OCC strategy consultants, which specialises in luxury apparel and beauty. “Even in China, this year a lot of fur companies have closed.”

She says the problem is two-fold: “There is a decline in terms of demand and there is the oversupply,” added to which Covid has made things worse as there is now nervousness within China about trading or importing animal products.

Ms Wang adds that the appetite for fur is changing among younger Chinese. Fake fur used to be seen as low quality, but consumers’ perceptions are changing as more luxury brands make the switch.

“We know that versus the previous generations, these younger consumers, especially Gen Z, have a higher sense of social responsibility – I do see that trend has started,” she says.

Read MoreFeedzy