How did three of this year’s fictional works end up being so connected to today’s crisis? Caryn James takes a look.

E

Emma Donoghue’s new novel, The Pull of the Stars, set during the 1918 pandemic, was meant to be published next year. However, when she submitted the final manuscript in March, just before Covid-19 shut down the world, her US and UK publishers found it so unexpectedly resonant that they rushed the book into print. “I feel a little sheepish”, Donoghue explains, about the timing. But, she continues, as a subject, “Pandemics are fabulous for a novelist. They are a way of making everyday life dangerous, and raising ethical dilemmas.”

More like this:

– The best novels you’ve never heard of

– Short stories for every taste and mood

Donoghue’s is the latest in a group of current novels written before the pandemic but arriving now in a landscape that makes them timelier and more piercing than the authors could have imagined. Maggie O’Farrell’s Hamnet is a lushly written immersion into the lives and minds of Shakespeare’s wife and their young son, Hamnet, who died in 1596, probably due to the bubonic plague. In Lawrence Wright’s exhaustively researched, chillingly prescient The End of October, a brilliant scientist tracks down a new virus that spreads across the world, causing the kind of quarantines, horrifying death tolls and social disruption that are all too familiar today. Wildly different in style and settings, all these novels use a pandemic as a lens on society at a moment of crisis. Extrapolating from history or from science, they highlight issues of public health, government responsibility and class divisions, and with a novelist’s eye consider how those forces affect individuals. High drama flows from the way pandemics threaten the most basic human needs, health and family.

Emma Donoghue’s new book The Pull of the Stars is set in a hospital during the 1918 flu pandemic (Credit: Alamy)

Broad social and intimately personal elements come together beautifully in the visceral yet eloquent The Pull of the Stars. The heroine and first-person narrator, Julia, is a nurse in a Dublin maternity ward for women with the flu. She is about to turn 30 and lives with her brother, who has returned from serving in World War One so traumatised that he hasn’t spoken a word since. As it follows Julia through three days in the ward, the novel displays the narrative pull, emotional warmth and psychological acuity Donoghue brought to her earlier novels. She is best known for the 2010 bestseller Room (she also wrote the screenplay for the 2015 film), and has dealt with health, trauma and motherhood in more historical settings, including The Wonder (2016), in which a nurse who trained with Florence Nightingale cares for a religious girl who claims she has lived for months without eating, and Frog Music (2014), set in San Francisco in 1876, during a smallpox epidemic.

One of Donoghue’s gifts is to use research to make a character’s experience come alive. In The Pull of the Stars, chapters are titled Red, Brown, Blue and Black, for the colours a person’s skin can turn as their flu worsens. There are accounts of excruciating pregnancies and births. Because we see events from Julia’s point of view, the precise, often bloody medical details fit organically into the novel. Even Julia’s patients have distinct personalities. One is middle-class, demanding and frightened. Another is a poor, unwed mother who refuses medication for religious reasons. Julia manoeuvres around condescending doctors who know less about childbirth than she does, and she is drawn to an uneducated but quick-witted young woman volunteer sent to help in the ward.

With its thoughtful heroine making life or death decisions, the novel would have been eye-opening and moving if it had been published at any time. But the dilemmas people encountered in 1918 are especially relevant today. For Donoghue, pandemics in fiction reach beyond their historical moment. “The way you have friends or family scowling at each other today over issues like, do we give a hug to a child or do we wear a mask,” she explains. “Similarly in 1918, your most ordinary decisions, like ‘do I get on the tram even though I’ve got a cough?’, become hugely ethical and existential questions.”

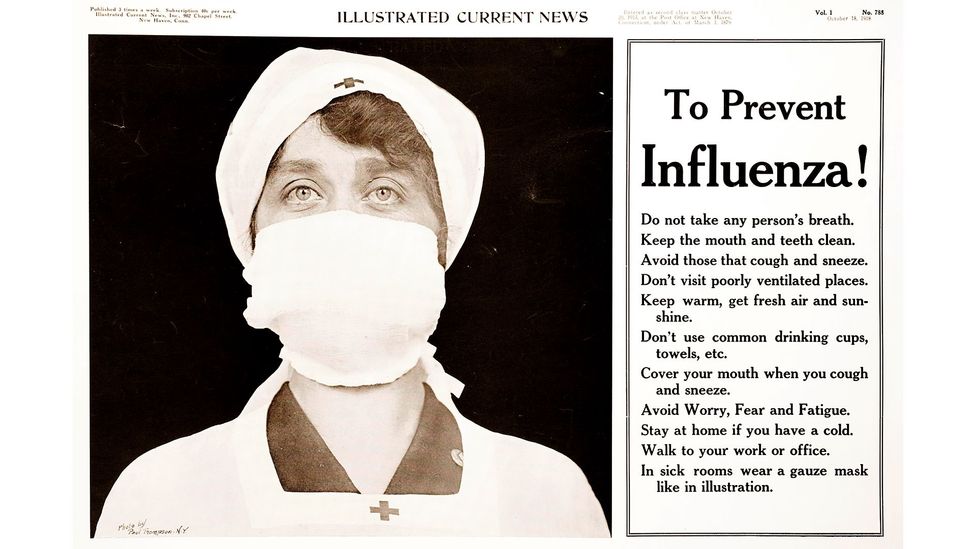

In the book, people’s everyday decisions – such as whether to take a tram with a cough – take on greater ethical significance (Credit: Getty Images)

In The Pull of the Stars, echoes of the current pandemic leap out. No visitors are allowed in the hospital, which is barely functioning under the load of cases. A sign posted outside says, ‘Refrain from shaking hands, laughing, or chatting closely together’. On the tram to the hospital, Julia glances at a newspaper headline reading ‘Increase in Reports of Influenza’ and thinks, “As if it were only the reporting that had increased, or perhaps the pandemic was a figment of the collective imagination.” A nursing nun arrives in the ward having seen a queue outside a cinema, and sneers, “Grown men, women, and children, all gasping to get into the great germ box”. The nun lacks compassion, but what are cinemas now if not great germ boxes? Throughout, Julia worries about her brother, and wonders about her own future. Will she ever marry? Become a mother?

By recreating the experience of pandemic so personally, Donoghue deals with enduring themes: how we handle crises, the need for human connection, and the cost of losing that connection. The novel also speaks profoundly to the stress of our own moment. Julia thinks: “I was having trouble foreseeing any future. How would we ever get back to normal after the pandemic?”

Accidental prophets

As different as it is, Hamnet is also very much concerned with motherhood. Hamnet Shakespeare, who died at the age of 11, is a major figure in the book, but the main character is his mother. We know Shakespeare’s wife as Anne Hathaway, but O’Farrell calls her Agnes, the name her father used in his will. The name change highlights how deeply O’Farrell imagines the life of a woman about whom historical knowledge is scarce. The fictional Agnes, smart and capable, can intuit people’s thoughts by grasping their hand between thumb and forefinger.

Maggie O’Farrell’s new novel centres on Shakespeare’s wife and family, with the bubonic plague looming in the background (Credit: Alamy)

Where the pandemic is central to The Pull of the Stars, in Hamnet it is a dark presence hovering over the book, just as the bubonic plague hovered over England throughout Shakespeare’s lifetime, having begun in the 14th Century as the ‘Black Death’. But it strikes Agnes’s family like lightning, depicted in ominous detail. Young Hamnet sees how sick his twin sister, Judith, is, and questions his mother. “‘She’s got . . . it,’ Hamnet says, in a hoarse whisper, ‘Hasn’t she?'” His hesitation makes clear what “it” means. Agnes knows the symptoms, the buboes, or lumps “straining at the skin” in her daughter’s neck and under her arms. Hamnet is frightened by a figure who appears at the door, “tall, cloaked in black, and in the place of a face is a hideous, featureless mask, pointed like the beak of a giant bird.” This turns out to be the doctor in a protective mask, who will not set foot in the house but delivers a message to the family. They must stay inside until “the pestilence is past.” O’Farrell’s audacious leaps of imagination may be rooted in the 16th Century, and her novel completed before scientists had even heard of Covid-19, but the fear and grief experienced during that era of plague is quite like our own.

The End of October, which Wright began in 2017, is based on research and interviews with scientists who have long seen a pandemic coming. The novel might have landed as a warning, but now its jaw-dropping parallels to the current crisis make it seem prophetic. Wright is a noted journalist who has written books about 9-11 and Scientology, and his novel is less literary in its ambitions than Donoghue’s or O’Farrell’s. Nevertheless, he creates a compelling narrative focused on the fictional Henry Parsons, an infectious disease specialist for the Centers for Disease Control in the US, who travels to Indonesia to investigate the first reports of a new disease. “It could be a coronavirus like Sars or Mers,” Henry speculates. Soon the fictional disease, called Kongoli flu, destroys national economies and sets off global political crises. Henry follows its trail to Saudi Arabia, where Mecca has to be quarantined during the Hajj. In real life, this year the Hajj was cancelled, one of the few points at which reality is not quite as bad as what Henry faces.

Lawrence Wright’s contemporary novel The End of October is based on research and interviews with scientists who have long predicted a pandemic (Credit: Getty Images)

Wright recognises that the crisis comes down to the personal. Henry worries constantly about his wife and two children at home in Atlanta, where the food supply is disrupted and the power grid goes out. His efforts to stop the disease come down to that: trying to save his family. But The End of October functions best in its reportorial details. It is stunning and appalling to observe how astutely Wright perceived the vulnerabilities in government and public health ready to cause havoc if a pandemic hit. In his fictional Washington the vice-president, who is in charge of the administration’s pandemic response, presses scientists for good news to tell Americans about a vaccine. They warn him that no vaccine or treatment is imminent, but he’ll settle for reassuring spin. “Can we have the president say that a vaccine is in development?” He doesn’t want to hear ‘no’. The scene would be perfectly plausible as a reported news story today.

Donoghue has made a similar observation about political leaders during pandemics. While she was editing the novel, she said: “I was hearing politicians come out with so many equivalents of the mixed messaging they put out in 1918, vague reassurances not based on scientific fact.. I came out of writing this book thinking ‘I will place my trust in science over politics anytime’.” Like this year’s other accidentally prescient plague novelists, Donoghue made no changes in her book to account for the new virus. She didn’t have to.

Love books? Join BBC Culture Book Club on Facebook, a community for literature fanatics all over the world.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.