image copyrightCNSA

China has launched a mission to try to retrieve rock samples from the Moon.

Its robotic Chang’e-5 spacecraft departed the Wenchang launch complex on a Long March 5 rocket early on Tuesday morning local time, and if successful should return to Earth in mid-December.

It’s more than 40 years since the Americans and the Soviets brought home lunar rock and “soil” for analysis.

China aims to be only the third country to achieve this feat, which will be an extremely complex endeavour.

It’s a multi-step process that involves an orbiter, a lander-ascender and finally a return component that uses a capsule to survive a fast and hot entry into Earth’s atmosphere at the end of the mission.

But confidence should be high after a series of well-executed lunar missions that started just over a decade ago with a couple satellites.

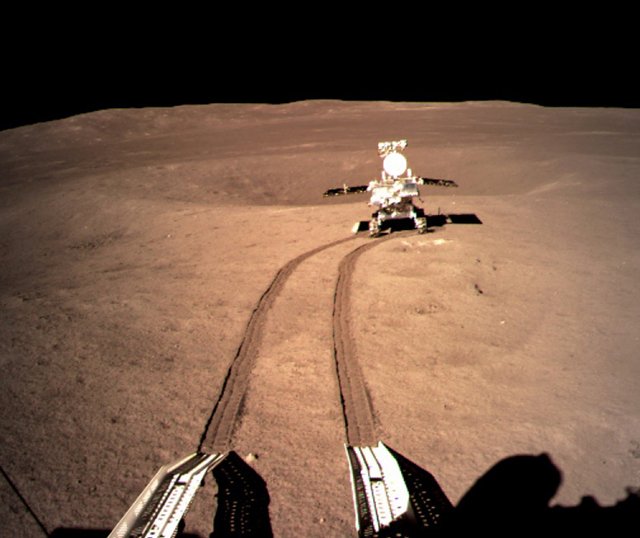

These were followed up by lander-rover combinations – with the most recent, Chang’e-4, making a soft touch down on the Moon’s farside, something no spacefaring nation had previously accomplished.

Chang’e-5 is going to target a nearside location called Mons Rümker, a high volcanic complex in a region known as Oceanus Procellarum.

The rocks in this location are thought to be very young compared with those sampled by the US Apollo astronauts and the Soviet Luna robots – something like perhaps 1.3 billion years old versus the 3-4-billion-year-old rocks picked up on those earlier missions.

This will give scientists another data point for the method they use to age events in the inner Solar System.

Essentially, researchers count craters – the older the surface, the more craters it has; the younger the surface, the fewer it has.

“The Moon is the chronometer of the Solar System, as far as we’re concerned,” explained Dr Neil Bowles at Oxford University.

“The samples returned by the Apollo and Luna missions came from known locations and were dated radiometrically very accurately, and we’ve been able to tie that information to the cratering rate and extrapolate ages to other surfaces in the Solar System.”

The new Chang’e-5 samples should also improve our understanding of the Moon’s volcanic history, said Dr Katie Joy from the University of Manchester.

“The mission is being sent to an area where we know there were volcanoes erupting in the past. We want to know precisely when that was,” she told BBC News.

“This will tells us about the Moon’s magmatic and thermal history through time, and from that we can start to answer questions more widely about when volcanism and magmatism was occurring on all of the inner Solar System planets, and why the Moon could have run out of energy to produce volcanoes earlier than some of those other bodies.”

image copyrightCNSA

When Chang’e-5 arrives at the Moon it will go into orbit. A lander will then detach and make a powered descent.

Once down, instruments will characterise the surroundings before scooping up some surface material.

The lander has the capacity also to drill into the soil, or regolith.

An ascent vehicle will carry the samples back up to rendezvous with the orbiter.

It’s at this stage that a complicated transfer must be undertaken, packaging the rock and soil into a capsule for despatch back to Earth. A shepherding craft will direct the capsule to enter the atmosphere over Inner Mongolia.

image copyrightCNSA

Every phase is difficult, but the architecture will be very familiar – it’s very similar to how human missions to the Moon were conducted in the 1960/70s.

China is building towards that goal.

“You can certainly see the analogy between what’s being done on the Chang’e-5 mission – in terms of the different elements and their interaction with each other – and what would be required for a human mission,” said Dr James Carpenter, exploration science coordinator for human and robotic exploration at the European Space Agency.

“We’re seeing right now an extraordinary expansion in lunar activity. We’ve got the US-led Artemis programme (to return astronauts to the Moon) and the partnerships around that; the Chinese with their very ambitious exploration programme; but also many more new actors as well.”

[email protected] and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos

Read MoreFeedzy