The strategic Bering Strait between Russia and the United States usually is plugged with a thick cork of sea ice in December, keeping most ships from sailing between the Arctic and northern Pacific oceans.

But not this year.

Following an extraordinary spring and summer of warm Arctic temperatures, and the shriveling of Arctic sea ice to its second lowest extent on record, the strait remained mostly ice-free into early December.

Taking advantage of the situation, two gargantuan liquified natural gas tankers — each measuring three football fields long — passed through the Bering Strait early in the month, one heading for ports in East Asia, and the other returning.

“This would have been utterly unthinkable even 10 years ago,” says Rick Thoman, an Arctic climate specialist at the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Thoman is one of the general editors of the recently released Arctic Report Card for 2020 — a comprehensive annual assessment published for the past 15 years by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

“As we state in the report card, the transformation to a wholly different Arctic than our parents and grandparents knew is wholly underway,” Thoman says. (For my full interview with Thoman, see the video embedded at the end of this story.)

For the 12 months between October of 2019 and September of 2020, Arctic surface temperatures on land were the second highest since at least 1900, according to the report.

Siberia was particularly hard hit, with record high temperatures and very early and rapid melting of snow. That contributed to “unprecedented” wildfire seasons in a large swath of the Eurasian Arctic.

For two years in a row, blazes in the sprawling Sakha region ignited earlier than ever seen before during the 20-year satellite record. The total area burned just between the months of March and June was nearly three times the 20-year mean.

Ordinarily, fires don’t ignite north of treeline in Siberia until July. But this past year they were already blazing in May, thanks to warm temperatures, the very early snowmelt, and “zombie fires” that came back to life after lying dormant under the snow from the year before. Some of this year’s blazes burned so far north that they came within miles of the Arctic Ocean.

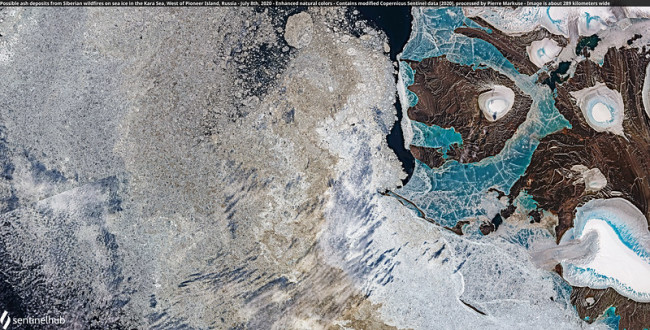

Possible ash deposits from Siberian wildfires is seen on sea ice in the Kara Sea just off the Siberian coast. The brownish deposits atop mostly white ice were seen by a Sentinel 2 satellite on July 8th, 2020. The image spans about 180 miles from left to right. (Credit: Copernicus Sentinel data processed by Pierre Markuse)

In both 2019 and again in 2020, smoke from Siberian wildfires spread for thousands of miles, reaching all the way across the Pacific Ocean to the United States and Canada — and beyond. And according to a recent report in Nature, this past year the blazes belched a record 244 million tons of climate-warming carbon dioxide into the atmosphere — 35 percent more than in 2019.

“I kind of resist the language about ‘a new normal,’ because there is no reason to think that in 30 years much of anything in the Arctic is going to look like it does today,” Thoman says. “The Arctic is in a transition, and there is absolutely no reason to think that this is not going to continue.”

The Polar Paradox

Just how different the Arctic ultimately will look will depend on how successful we are in reducing the emissions of CO2 and other greenhouse gases that are causing the Arctic to warm more than twice as rapidly as the global average. Although we actually are making some progress, it’s arguably being hampered by development of Arctic oil and gas reserves.

Call it the “polar paradox,” a phenomenon epitomized by those giant liquified natural gas tankers cruising through a relatively ice-free Bering Strait in December. Even as Arctic nations give lip service to reducing greenhouse gas emissions to prevent dangerous climate change, they are taking advantage of a warmer climate to develop Arctic oil and gas reserves, which of course only enhances the warming in a self-reinforcing feedback loop.

“A more accessible Arctic, potentially at least, makes it easier to continue down the track we’ve been,” Thoman says.

That track promises to lead to valuable riches: The USGS estimates that about 30 percent of the world’s undiscovered natural gas, and 13 percent of the undiscovered oil, may be found in the Arctic, mostly offshore. It amounts to some 90 billion barrels of

oil, 1,669 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, and 44 billion barrels of natural gas liquids.

Drilling for those resources, and shipping it to markets, will never be easy in such a harsh environment. But as the climate has warmed, it has become increasingly feasible.

The liquified natural gas those tankers carried came from a giant $27-billion plant completed just a year ago on the shore of the gas-rich Yamal Peninsula in Russia’s Arctic. It’s part of a big play by Russia to develop oil and gas reserves in the high north.

The Northern Sea Route

Fifteen ice-breaking LNG tankers have been built to ship gas from the remote Yamal plant to Western Europe and East Asia using a shipping corridor called the Northern Sea Route. They are supposed to be capable of operating year-round. But for most other ships, the NSR usually is open just between June and October. This year, with early and rapid melting of sea ice, the route opened a month earlier.

This year, about 30 voyages to Asia were completed along the Northern Sea Route — a record number. Two years ago, just four voyages were completed. All told, ships carried 32 million tons of cargo along the route this year, up from a little more than 20 million tons in 2018.

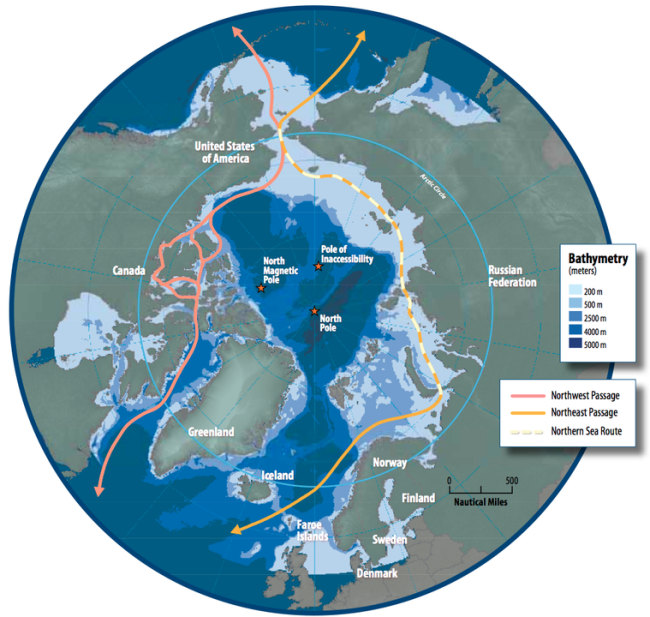

Map of the Arctic region showing the Northern Sea Route, along with the Northeast Passage, which extends the route to Western Europe, and the Northwest Passage. Also marked is the “pole of inaccessibility,” a spot in the Arctic Ocean that is farthest from any landmass. (Credit: Arctic Council via Wikimedia Commons)

Stretching for 2,800 miles across the top of Russia, the NSR is a much shorter option for shipping cargo between East Asia and Western Europe than the Suez Canal. For a ship making the entire passage, it cuts 8,000 miles from the journey and reduces transit time by 10 to 15 days.

Hoping to enable year-round use of the sea route, Russia has been on an icebreaker-building spree. In 2019, Russian President Vladimir Putin said the country would operate 13 heavy-duty icebreakers in the Arctic, most of them nuclear-powered.

As a polar bear and its cub go about their business, the Russian nuclear-powered icebreaker Arktika crunches through sea ice during its voyage in October to the North Pole. (Credit: Rosatom Global via Twitter)

This year, Russia launched what it says is the world’s most powerful ice breaker, the 560-foot long Artika. Capable of breaking through ice nearly 10 feet thick, the ship took a detour to the North Pole on its shakedown cruise from St. Petersburg to its home port in Murmansk. Arktika reached the pole on Oct. 3, 2020.

The trip is not very likely to go down as one of the more demanding ones Arktika will face during its lifetime: The icebreaker had relatively scanty ice to break. That’s in part because the edge of the sea ice had retreated farther north than ever seen before.

Russia isn’t the only country that’s racing to develop its Arctic fossil fuel reserves. Norway is heading down the same path too.

Norwegian Supreme Court: Arctic Drilling is Constitutional

On December 22, Norway’s Supreme Court rejected an effort to curtail the government’s plans for oil exploration in the Arctic. In doing so, it rejected arguments from climate activists that the country’s constitutional right to a clean environment required that drilling be stopped. As a result of the decision, drilling sanctioned by permits given in 2016 can go forward, as can other plans.

In their decision, the judges said Norway was not legally responsible for emissions of carbon dioxide resulting from oil the country exports. In so many words, they said that’s on the countries that burn the oil, not on Norway.

“The supreme court’s brutal ruling was just another confirmation of the darkness,” says Andreas Ytterstad, chair of Concerned Scientists Norway, and a researcher at Oslo Metropolitan University. “I was depressed, to be frank with you, but I also think it was claryfing.”

What seems clearer than ever is that as long as demand continues for fossil fuels, we shouldn’t expect countries like Norway and Russia to resist the economic temptation to meet that demand.

“National interests or corporate interests often diverge from planetary scale interests,” Thoman observes. “That’s the world we live in.”

And that means whether we like it or not, it really is on us.

Note: I recorded my interview with Rick Thoman on Zoom. We covered much more than I was able to include in this article. So if you’re interested, have a look at the video I embedded below. Please be aware that the virtual background Rick chose to use caused some odd effects. But he said he was fine with my posting the video. So I hope our conversation will be engaging and informative.