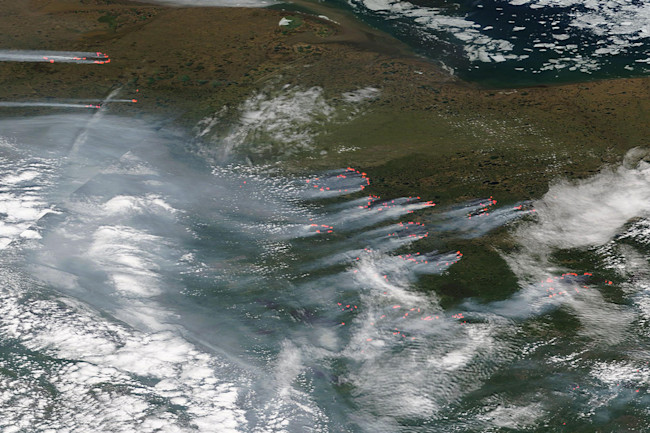

Wildfires have been raging across Siberia all spring and now into summer, including many above the Arctic Circle. This image combines data acquired by NASA’s Terra satellite in the visible and infrared portions of the spectrum to show smoke plumes and hot spots from fires on July 1, 2020. It’s about 375 miles across. (Credit: Terra MODIS data from NASA Worldview processed by Tom Yulsman)

The first of several monthly analyses of the global climate is now in, and it’s not much of a surprise: Last month finished in a virtual tie for warmest June on record.

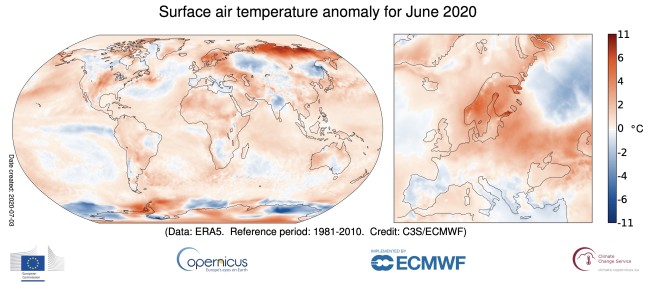

The analysis, from the Copernicus Climate Change Service in Europe, finds that global temperatures in June added up to 0.53?C warmer than the long-term average for the month. That’s a virtual tie with June of 2019.

In particular, extraordinary warmth in Siberia helped push the global average for the month into that record-tying territory. Temperatures across the entire region averaged about 9 degrees F above normal last month.

Here’s how temperatures at Earth’s surface departed from the long-term average in June, both globally and in Europe. (Credit: Copernicus Climate Change Service/ECMWF.)

“A few places bordering the Laptev Sea in northeast Siberia spent the month 18 degrees above normal,” writes Washington Post meteorologist Matthew Cappucci. “An anomaly like that would be the equivalent of New York City averaging a high of 104 and low of 87 degrees every day during the month of July.”

Arctic Wildfires

The warmth in Siberia led to a record-setting meltdown of the region’s snowpack this spring, exposing soils to the Sun earlier than usual and thereby drying them out quickly. This and the warm temperatures generally have helped stoke wildfires that began very early this year and have only expanded and gotten worse. Many are blazing well above the Arctic Circle.

“Higher temperatures and drier surface conditions are providing ideal conditions for these fires to burn and to persist for so long over such a large area,” says Mark Parrington, a senior scientist at the Copernicus climate service. “We have seen very similar patterns in the fire activity and soil moisture anomalies across the region in our fire monitoring activities over the last few years.”

In a recent Tweet, Parrington said the “scale & intensity of #Siberia/#Arctic #wildfires in June 2020 has been greater than the ‘unprecedented’ activity of June 2019.”

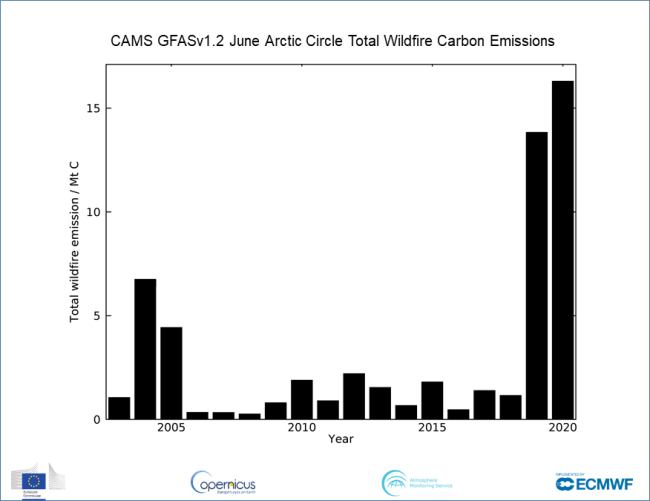

Unprecedented fires in Siberia pushed emissions of heat-trapping carbon dioxide from burning vegetation to new heights in June. (Credit: Data from CAMS/ECMWF. Image courtesy Mike Parrington via Twitter)

Ironically, burning Siberian vegetation is contributing to global warming by emitting large amounts of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. And that, of course, contributes to warming, which only makes the risk of fire higher.

“The number and intensity of wildfires in the Sakha Republic and Chukotka Autonomous Oblast and, to a lesser degree, parts of Alaska and the Yukon Territories, have been increasing since the second week of June and have resulted in the highest estimated emissions in the 18 years of the CAMS dataset,” according to the Copernicus Climate Service. “For June, an estimated total of 59 megatonnes of CO2 were released into the atmosphere, which is more than last year’s June total of 53 megatonnes of CO2.”

The problem is compounded by permafrost that’s melting in the Siberian heat, releasing more carbon into the atmosphere.

Arctic Amplification Gets Worse

For many years now, scientists have been saying that the Arctic is warming about twice as fast as the rest of the world, a phenomenon known as “Arctic amplification.” But the data now show that this may well be obsolete.

“The Arctic warming is getting a lot of attention this week, but I keep seeing references to the warming being twice as fast as the global mean, and that’s not right,” says Gavin Schmidt, director of NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies, writing n a recent Tweet. “It’s more like 3 times the global mean.”

Schmidt’s institute will soon publish its own analysis of the global climate in June, as will the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. These independent assessments may vary a bit in the details, but the broad picture is likely to be same in all three analyses.