This story appeared in the September/October 2020 issue as part of Discover magazine’s 40th anniversary coverage. We hope you’ll subscribe to Discover and help support our next 40 years of delivering science that matters.

From the October 1980 Issue

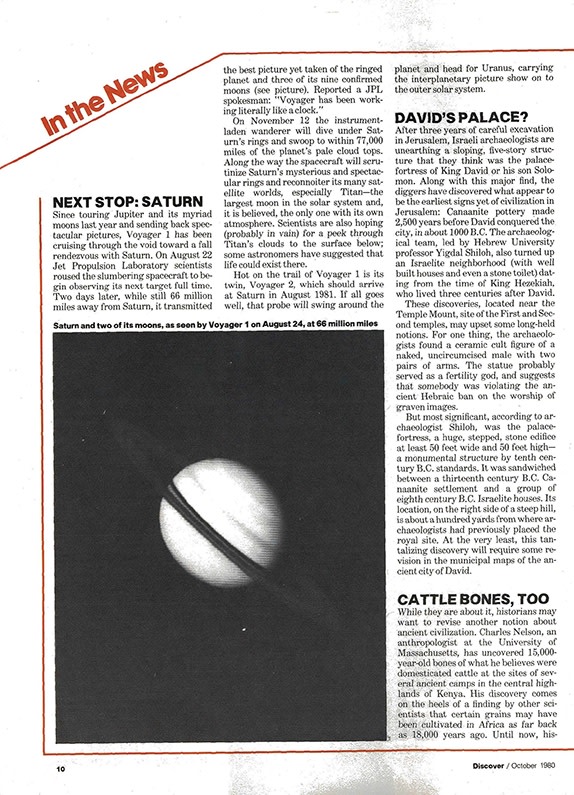

Since touring Jupiter and its myriad moons last year and sending back spectacular pictures, Voyager 1 has been cruising through the void toward a fall rendezvous with Saturn. On August 22, [1980], Jet Propulsion Laboratory scientists roused the slumbering spacecraft to begin observing its next target full time. Two days later, while still 66 million miles away from Saturn, it transmitted the best picture yet taken of the ringed planet and three of its nine confirmed moons. Reported a JPL spokesman: “Voyager has been working literally like a clock.”

The story as it originally appeared in the October 1980 issue of Discover.

On November 12 the instrument-laden wanderer will dive under Saturn’s rings and swoop to within 77,000 miles of the planet’s pale cloud tops. Along the way the spacecraft will scrutinize Saturn’s mysterious and spectacular rings and reconnoiter its many satellite worlds, especially Titan — the largest moon in the solar system and, it is believed, the only one with its own atmosphere. Scientists are also hoping (probably in vain) for a peek through Titan’s clouds to the surface below; some astronomers have suggested that life could exist there.

Hot on the trail of Voyager 1 is its twin, Voyager 2, which should arrive at Saturn in August 1981. If all goes well, that probe will swing around the planet and head for Uranus, carrying the interplanetary picture show on to the outer solar system. — Discover staff

2020 Hindsight: Voyaging Beyond

It’s been almost 40 years since NASA’s Voyager 1 spacecraft soared beneath Saturn’s rings. The Nov. 12, 1980, flyby forever changed our understanding of the planet. The probe discovered three new moons and an additional ring surrounding Saturn. It also learned that the atmosphere of the planet’s largest moon, Titan, is made mostly of nitrogen — like Earth’s.

Launched in 1977, Voyager 1 and its twin, Voyager 2, went on to study Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune up close, taking advantage of a rare alignment among the outer planets. And while the project was only approved to fly by Jupiter and Saturn at launch, the probes would ultimately complete a planetary grand tour. As Voyager 2 cruised toward Neptune, NASA even expanded the size of its earthbound satellite dishes to receive the inevitably weak radio signals the craft would send from our most distant planet. Together, the two probes studied all of the four outer planets, giving astronomers fresh insights into some of our solar system’s biggest mysteries.

Voyager 1 also gave us a new way to think about our place in the universe. In 1990, the spacecraft captured the now-iconic image of Earth known as “The Pale Blue Dot,” a lone azure speck in a sea of empty space. By then, the craft was about 3.7 billion miles from the sun — already past Neptune and hurtling out of our solar system — when it turned back to snap 60 photos of Earth and five other planets. Shortly thereafter, it powered off its cameras for the last time.

The Voyagers are now the longest-operating — and most distant — spacecraft in history. In 2012, Voyager 1 became the first spacecraft to enter interstellar space, a boundary that begins at the point where the sun’s magnetic field stops influencing its surroundings. Its sibling crossed that celestial threshold in 2018, and is still revealing new secrets about the cosmos. Just last year, a series of studies in Nature Astronomy showed what Voyager 2 found during its crossing, helping define the “cosmic shoreline” between our solar system and everything beyond. — Alex Orlando