10 dream homes from the past century

From a Modernist desert retreat to a camouflaged turf lodge, a new book, Houses: Extraordinary Living, explores the diversity of some of the world’s most awe-inspiring abodes.

T

This article was originally published in 2019

Home should be a sacred space: the place where you feel secure, and can unwind at the end of a long day – it’s also where we entertain friends, and increasingly, a place to work or study. New methods and materials introduced since the early 20th Century have offered architects and daring clients around the world new ways to let creative imaginations run wild in how – and where – people are able to live.

A new book, Houses: Extraordinary Living, charts our shift in taste, style, and thinking about domestic living through a cross-section of innovative residences that fully embrace their environment – from a hidden house in a Swedish forest to a California desert retreat. Levitating glass boxes, experimental prototypes, radically open-plan layouts, and residences that relate to their surroundings – with the right architect, no project is impossible.

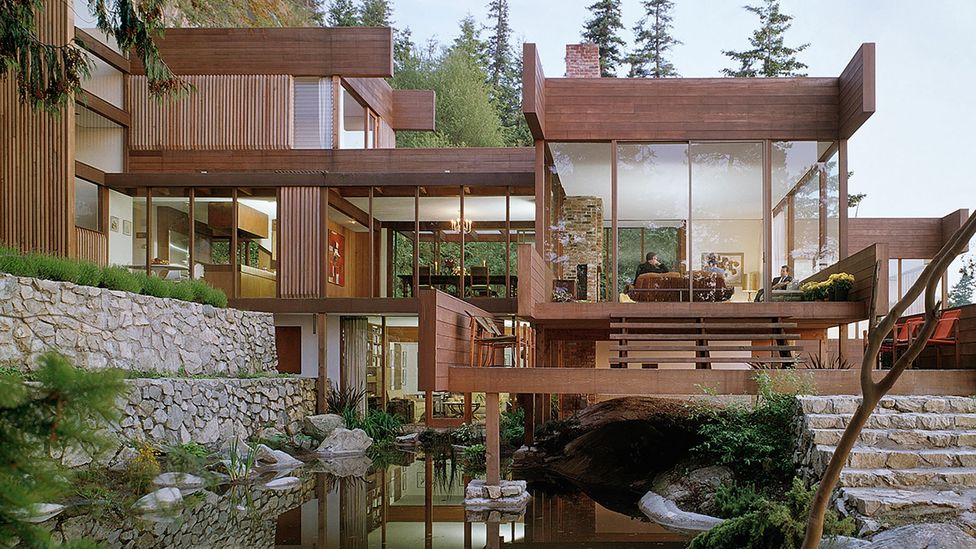

Graham House, Canada

Set on a sheer cliff, the Graham house descended the slope in four levels (Credit: Ezra Stoller/Esto, Courtesy F2 Architecture)

Prominent Canadian architect Arthur Erickson designed this west coast Modernist house on an incredibly steep site in West Vancouver, alongside long-time collaborator Geoffrey Massey. Building on the difficult, rugged cliff face was completed in 1963 with a design of hovering horizontal beams and glass which enclosed the major living areas, as a multi-storey structure descending the slope in four levels, from the carport to the rocky bluff over the Pacific.

Each area opened onto a roof terrace over the floor below, to achieve maximum access to the stunning views. The late Erickson wrote that: “The Graham house launched my reputation as the architect you went to when you had an impossible site.” Despite its prestige, sadly the Graham house was demolished in 2007.

Desert House, United States

The concrete wall enclosure subverts Desert Modernism’s openness (Credit: Jim Jennings Architecture)

Architect Jim Jennings and writer Therese Bissell took their time building their elegant desert retreat. After purchasing the land in 1999, a decade passed before the couple spent time in their Palm Springs refuge: “When you’re your own client, you can be as demanding as you like,” Jennings told Architectural Digest. “And you know how difficult everything will be, especially when it appears simple.”

Rather than opening to the outdoors, the space subverts Desert Modernism’s tradition of the post-and-beam glass box by enclosing the living area in a 2.4m concrete wall of horizontal blocks, supporting a steel roof and two courtyards. From inside, views of the surroundings – palm trees, the San Jacinto Mountains, and molten blue sky – are framed by the floating flat roof, with overhangs providing much-needed shade.

Edgeland House, United States

The turf roof keeps the building warm in winter and cool in summer (Credit: Paul Bardagjy)

Architects Bercy Chen Studio adopted a modern interpretation of the Native American pit house as a model for Edgeland House, digging 2m into the ground in an attempt to restore the land of a former brownfield site which had been scarred by industry in Austin, Texas.

Completed in 2012, the turf roof and sunken excavation provides both privacy from the street side and insulative properties to keep the building warm in winter and cool in summer. The lack of any connecting hallway between the living and sleeping quarters is intentional – encouraging its owners to spend more time outside.

House in Itsuura, Japan

The treehouse-style timber home is embedded in the sloping landscape (Credit: Life Photo Works Osamu Abe)

This single-storey angled house in Japan’s Ibaraki Prefecture is perched on two organically formed pillars, which allow the rest of the structure to be embedded in the hill. The interiors are timber-clad with wood from the local area, and the facade features external angled slats that regulate temperature, let in light and provide privacy.

Living spaces are in the longer wing of the structure, while the shorter wing has spaces for sleeping. Architects Life Style Koubou planted 60 trees to help regenerate the area, and over time it’s hoped the dwelling will become more connected to its natural surroundings as the wood takes on a weathered appearance.

Bakkaflot 1, Iceland

Bakkaflot dissolves into the landscape, leaving just the roof visible (Credit: Iris Ann)

Shortly after graduating from Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris 1960, Hogna Sigurdardottir became the first woman to design a building in a professional capacity in Iceland. A few years later, she would design arguably one of the country’s greatest buildings in the form of a simple modern turf hut for a family in a suburban street south of Reykjavik.

In 1963, Sigurdardottir told the family of six “I am going to make you a nest”, and in incorporating three mounds to protect the low house from the harsh Icelandic elements, she kept her promise. The house is made of exposed concrete using Brutalist techniques, as is much of the furniture – such as the sofa and the bathtub – creating a connection between inside and out.

The House on the Cliff, Spain

The zinc-clad roof has the appearance of scaly dragon skin (Credit: Jesus Granada)

Rippling over the contours of a steep hillside slope in Granada is a largely-buried dwelling which architects Pablo Gil and Jaime Bartolome called “a contemporary Gaudiesque cave” after Anton Gaudi, known as the greatest exponent of Catalan Modernism. Completed in 2015, the two-storey residence uses the natural cooling of the earth to maintain a constant temperature of 19.5C.

Covered with a curved double shell of reinforced concrete upon a metal frame, its rolling zinc-tiled, handcrafted roof resembles a dragon’s scaly skin, with its pool and cantilevering terrace framing views over the Mediterranean sea. The architects stated: “The metallic roof produces a calculated aesthetic ambiguity between the natural and the artificial, between the skin of a dragon set in the ground, when seen from below, and the waves of the sea, when seen from above.”

Dragspel House, Sweden

The cabin can be adjusted to its environment depending on the weather (Credit: Christian Richters)

Dragspel means accordion in Swedish, referencing the folds of red cedarwood shingles on this extension to an original cabin from the late 19th Century, located on the shore of the lake Ovre Gla. The organic shape of the house blends naturally into the Glaskogen nature-reserve setting, and is designed to have a minimal visual impact, with the windows hidden within the skin of the structure.

In due time, the wood of the cabin skin will have a grey appearance, blending into the rough, rocky forest landscape. Another neat trick: during the summer, the front part of the cabin can be extended to cantilever over a stream, with the windows opening wide to listen to the murmur of the water, and can then be retracted in the winter or on rainy days – adjusting itself to its environment depending on the season or number of guests.

Till House, Chile

The roar of the sea is constant in this Chilean shelter (Credit: Sergio Pirrone)

Cut into a deep shelf on a Chilean coastal landscape in Navidad, this small weekend shelter built for a couple on a coastline of cliffs is surrounded on three sides by the roaring Pacific Ocean. Invisible from the road, its open-plan terrace is perfect for lounging with panoramic views, while the rest of the space is for sleeping and eating.

Individual rooms are sectioned off with shelving units to provide privacy, and the entire roof is a massive open deck which is reached by the cliffside walkway. If that wasn’t enough for relaxation, there is also a wooden jacuzzi called a cuba, where the water is warmed with a fire.

Kirsch Residence, United States

The concrete enclosure’s windows maximised solar gain (Credit: Errol Jay Kirsch Architects)

In the suburb of Oak Park, Illinois, you would think Frank Lloyd Wright’s home and studio would be the highlight – that is, until you drive by this massive bunker built in 1982 by Errol J Kirsch which resembles the kind of structure more commonly seen in science-fiction movies.

Enclosed in concrete, the Kirsch residence’s unusual geometric form gives a sense of security – but that’s not all: the sharply pitched roofs, ziggurat form and slit windows were designed for energy efficiency by inhibiting temperature changes and windows that maximise solar gain.

Malator house, Wales

Inside the hill, an ellipse-shaped glass frontage opens to the sea (Credit: Architecture UK/Alamy)

Converted from old military barracks by Future Systems husband-and-wife architects Jan Kaplicky and Amanda Levete, the Malator House – or the ‘Tellytubby house’, as locals have dubbed it – is a two-bedroom holiday retreat sunk into an artificial hill overlooking the Pembrokeshire coastline.

Built in 1998 in the Earth-house style, its plywood roof is camouflaged with grass, making it practically invisible. The inside space is divided by multicoloured service pods containing the bathroom and kitchen, and the living room with a large sofa and fireplace. The only clue that there is habitation inside the hill is an elliptical window, like an eye looking out to sea.

Houses: Extraordinary Living is published by Phaidon.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.